Steven Soderbergh first worked with actor/monologue artist/diarist-poet Spalding Gray in 1996, filming the show Gray's Anatomy, which dealt with Gray's health troubles (a problem eye) and anxieties at the age of fifty-two, which was the age at which his mother had killed herself. After Gray's own suicide in 2004, Soderbergh has returned to fashion a documentary/tribute that's loving, moving and funny.

Gray's Anatomy was made during Soderbergh's wilderness years after the wildfire hit of sex, lies, and videotape and before the comeback collaboration with George Clooney. It's very good indeed, although Jonathan Demme's Swimming to Cambodia (1987) is my first and favorite Gray piece, with Nick Broomfield's Monster in a Box (1992) in a respectable third place. The new film is more of a creative work from Soderbergh, however, since it weaves together existing footage of Gray performing or talking, to create an overall narrative of the man's life. The material varies in technical quality, and the opening shot prepares us for this by using the glitchiest source material of all, seemingly a VHS tape. While Gray's Anatomy worked hard to provide a stimulating visual accompaniment to Gray's stories, without distracting attention from the words, here we really get the unadorned tales straight from the late star.

However much or little material there was to choose from (and I would expect there was a lot: Gray admits to being a born performer who acted from early childhood simply because it seemed natural to him) Soderbergh and his team have done a marvelous job of crafting a story that flows smoothly, encapsulates dramatic highs and lows, mixes tones deftly, and suggests reasons underlying Gray's self-destructive side without indulging in glib psychoanalysis (except where Gray ventures to analyze himself). By following the evolution of his performance work as well as the story of his life, we get a gradual darkening of tone: in later years, Gray was less concerned with portraying himself as a nice guy or with providing humorous pay-offs to the often distressing events he described. And yet we also see the happy family man who became a father late in life, and clearly loved it.

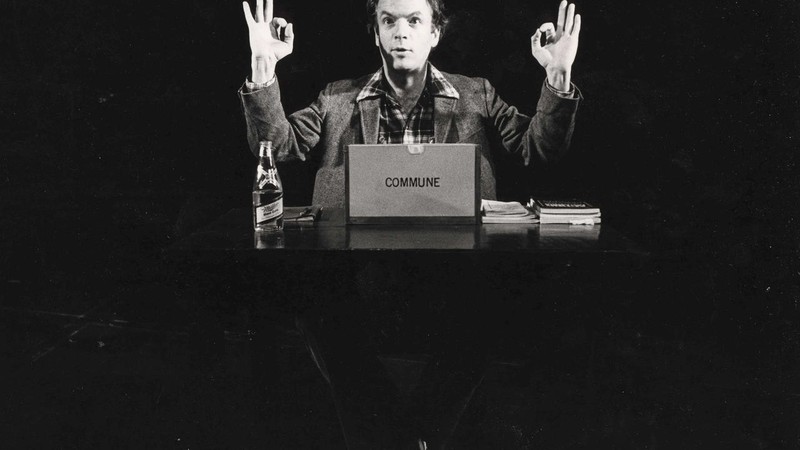

For those familiar with part of Gray's life and work, like myself, the film is illuminating about his early life as an actor, providing insights not available merely from the shows or the published books based on the monologues: I never knew Gray was such a handsome young fellow, looking like an intense Jean-Louis Trintignant. It's a shock somehow for me to see him performing and looking younger than I am now. And now he's dead, and you can't get any older than that. For those unfamiliar with any of Gray's writing-acting, the film serves as an intriguing introduction, for sure, and also as a life in fast-forward, in which Gray at different ages returns again and again to the subject of his own death, and the chaos of the universe, and the hope of imposing some structure on it via art.