THE MAGIC LANTERN

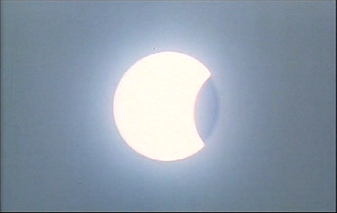

The sun vanishing behind the moon forms the opening image of Bill Douglas's final film, Comrades, subtitled A Lanternist's Account of the Tolpuddle Martyrs and What Became of Them. And shortly after its initial release in 1986, the film vanished too, killed by critical and public indifference. A few VHS tapes circulated, but decades were to pass after the director's premature death before his work would be discovered by an international audience, starting with the release by the BFI of his autobiographical trilogy My Childhood, My Ain Folk and My Way Home, and continued by the DVD debut of this, much larger work (which naturally looks a lot better than these frame grabs, for whose low quality I must apologise).

I hesitate to say "more ambitious," because the early, small-scale films evoke the private hell of a deprived childhood, with Bressonian sharpness of attention, and that doesn't seem like a small thing to achieve. But Comrades has a wider scope, a bigger budget and a longer running time - and a more overt political story.

FROM PLOUGH, FROM ANVIL, AND FROM LOOM

The Tolpuddle Martyrs were a group of 19th century English labourers who formed a "friendly society"—in effect, a trade union—to protest against the continual lowering of their wages. Invoking an obscure and ancient law against the swearing of oaths, the local landowner complained to the prime minister, and the men were arrested and transported to Australia, to serve a seven-year sentence of indentured labour under the harshest conditions. Meanwhile, in England, the martyrs became a cause celebre, resulting in their sentences finally being overturned.

In tackling this slice of history, Douglas eschewed the traditional tropes of the British period movie, avoiding nostalgia, romance, and larger-than-life heroics. His film is epic in the sense meant by Brecht, rather than that of David Lean, and he even shows, in parallel with the story, the development of early, pre-cinematic entertainments. The lanternist, in fact a disparate group of characters played by one actor, the great Alex Norton, pops up throughout the story, on opposite sides of the Earth at more or less the same time, and takes a bow at the end. Britain's top TV critic, Barry Norman, complained that "I was always aware I was watching a film." Apart from these moments of theatrical verfremdungseffekt, Douglas stages his action with simplicity and force, influenced by Bresson—insert shots often make up the bulk of a scene, and the editing imparts a measured weight and force to each action. As a somewhat incongruous contrast, the photography in the early scenes of Dorchester has a rather glossy, artificial feel: graded filters darken the sky, and coloured gels give us orange firelight and blue moonlight. It feels a little like a Ridley Scott commercial of the period, but the resemblance is at least partially quashed by the stark treatment of landscape and the understated narrative.

Casting the film, Douglas resisted featuring stars in his star roles, allowing the martyrs to truly be of the people, no more familiar to us than the players cast as their wives and children (although fate has tripped him up a little, since one of them, Keith Allen, now enjoys a form of tabloid stardom as the father of pop songstress Lily Allen, and Imelda Staunton has become a fixture in the films of Mike Leigh). Instead, the cream of British theatrical talent is funneled into the supporting roles of toffs and tradespersons: Robert Stephens, Barbara Windsor, Michael Hordern, Vanessa Redgrave, Freddie Jones, Murray Melvin and James Fox add a certain showbiz sparkle, but they are used for their artificiality compared to the simple expressiveness of the heroes.

Douglas also tried to secure the services of Stephen Archibald, who had played the boy in his autobiographical trilogy. But Archibald was in prison. Douglas wrote to the governor, arguing passionately that this film might be the young man's last chance to turn his life around. The governor refused a parole. Archibald, who never made another film, died in 1998, aged 39.

REMEMBER THINE END

By that time, Douglas himself had been dead eight years, cut down before he could accomplish a fraction of what he was clearly capable, screenplays based on James Hogg's Confessions of a Justified Sinner (a sort of rural Jekyll and Hyde tale with religious and satirical undertones) and the life of Eadweard Muybridge, progenitor of the cinema.

Douglas left behind him a vast collection of early cinema ephemera, and a few films. Comrades, a socialist cri de coeur made at the height of Thatcher's right-wing reign, is stirring, soft-spoken, at times strange, and perhaps a forgotten masterpiece. It's last image: a projector lens beaming right into the audience, as if to interrogate us.

***

The Forgotten is a regular Thursday column by David Cairns, author of Shadowplay.