Of my cinematic blind spots, Hans-Jürgen Syberberg is the most salient. The critical acclaim and gargantuan volume of the German filmmaker’s output suggest a mountain still to be discovered, so I recently began climbing. Rather than starting with Hitler: A Film From Germany, the director’s most famous work (available, incidentally, at the director’s own website, www.syberberg.de), I chose 1982’s Parsifal for my first Syberberg brush, mainly due to its comparatively less intimidating length (a “mere” 255 minutes, as opposed to Hitler’s 410 minutes) and also to my fascination with opera. Of course, Wagner’s last opus is to Syberberg no less a fascinating cultural monstrosity than Der Fuhrer, and expectations of an impersonal recording of a stage performance are dashed as soon as the camera lingers sinuously over pictures of post-WWII German devastation during the opening credits.

Wagner’s opera is a supremely loaded work, rich in Bavarian historical and religious themes, a strange, intense mélange expressed through insinuating leitmotifs. Still, even at the height of my youthful passion for opera (after an early Nineties attendance of Les Misérables—hey, you gotta start somewhere), Parsifal felt like one of the composer’s least appealing librettos, surely not the “attempted assassination of basic ethics” Nietzsche wrote about but a heavy and at times discordant work. It’s this discordance, indeed, that intrigues and excites Syberberg: The uneasy blend of Christianity, paganism, purity, madness and chromaticism needs to be confronted, decoded and situated within the nation’s cultural history. Syberberg’s method for this emerges gradually. Despite such eccentric aesthetic decisions as depicting the spearing of King Amfortas as a bit of puppet theatre, Act I proceeds un-jarringly. The mythical tableaux are set up on stage and the camera slowly snakes through them, the proscenium is acknowledged in the form of a rocky profile of Wagner that sprouts from the ground. So far, so Powell-Pressburger. The first shock comes as the film’s rather bovine Parsifal is taken to the hall of the Grail and a scarlet swastika is included among the flags lining the corridor. Its inclusion is a reminder of the opera’s ode to purity that appealed to Hitler, and that Syberberg’s goal is not just to visualize Wagner, but also to question and disrupt him.

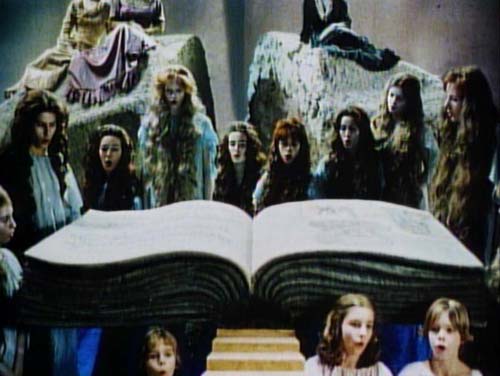

Things get wackier in Act II, due largely to the way Parsifal’s feral Mary Magdalene, Kundry (personified by the great, great Edith Clever), is allowed to seize the spotlight. Hitherto seen as a raggedy Lilith, Kundry is enlarged by her need for both sexuality and spiritual redemption, and when she kisses Parsifal the film foregrounds the hero’s own split. Literally—thus far played by Michael Kutter like a reject from Hair, Parsifal now suddenly morphs into a grave maiden played by Karin Krick, whose Joan of Arc features further unbalance the dubbed-in masculine tenor (by Reiner Goldberg) that continues to emerge from the character. Syberberg’s mise-en-scène mutates as well. Mammoth sets decompose only to be revived, props come to embody the filmmaker’s interpretations; castration imagery abounds, from the severed obelisk Klingsor the Sorcerer leans against to Amfortas’s wound, which is detached and, resembling a bleeding vagina, paraded around on a cushion. The sweep of the opera is complicated by projected images and insistent dry-ice smog (to quote one of the robotic wags from Mystery Science Theater 3000, “The movie The Fog didn’t have this much fog”), and compositions aping Friedrich and André Gill’s notorious caricature of Wagner are included among the intertextual transmutations. As Syberberg pushes on into Act III, the notion of narrative (even a Brechtian one) dissolves into a gallery installation about Wagner’s beliefs, icons and prejudices. Watching it without prior knowledge of Syberberg’s other work brings to mind Beckett’s line in Murphy, regarding “difficult music heard for the first time.”

Neither a stylized yet faithful recording (Bergman’s The Magic Flute) nor a conventional “opening-up” (Losey’s Don Giovanni, Rosi’s Carmen) of its stage source, the film is an odd fit in the sub-subgenre of cinematic opera adaptations. Floating on his own ether, Syberberg seems closer to French pioneer Abel Gance than to Teutonic New Wavers like Fassbinder, Herzog and Wenders. Like Gance, he combines the sprawling and the intimate, pageantry and insight, showmanship and artistry; it may be no accident that the return of the Arthurian knights near the end resembles a ragtag march of the dead out of J’Accuse). More to the point, both filmmakers see cinema as an ark in which all other previous art stirs. Thus, Parsifal is meant to encompass not only Wagner but also Nietzsche, Marx, German Romantic painting, the silent works of Lang and Murnau, etc. Facets of German art are summoned as part of Syberberg’s cultural exorcism, leading to a surprisingly hopeful finale that seems to bridge male and female, Aryan and Jew, theater and film. Watching Parsifal, I thought of Andrew Tracy’s splendid recent piece on The Auteurs about Berlin Alexanderplatz. Without taking a thing away from that Fassbinder masterpiece, I started wondering if Syberberg wouldn’t have been a better choice for filming Döblin’s novel. But why waste time wondering, when Hitler and Ludwig: Requiem for a Virgin King are still waiting to be watched?