You don’t necessarily think of Manny Farber as your Baedeker to the shadings and luridities of mainstay American movie acting, as a dab hand of the concise plot summary that uncoils into deft film critique, or associate him with audience recommendations and words like “marvelous,” “sensitive,” “poignant,” and “sparkling.” You particularly don’t think of Farber this way if your experience of his writing is confined to Negative Space. Yet consider three short illustrative moments from his many, sometimes-weekly film columns of the 1940s and '50s.

This is Farber on Frank Sinatra & Co. in From Here to Eternity for The Nation, August 29, 1953:

The laurel wreaths should be handed out to an actor who isn’t even in the picture, Marlon Brando, and to an unknown person who first decided to use Frank Sinatra and Donna Reed in the unsweetened roles of Maggio, a tough little Italian American soldier, and Lorene, a prostitute at the “New Congress” who dreams of returning to respectability in the states. Sinatra plays the wild drunken Maggio in the manner of an energetic vaudevillian. In certain scenes––doing duty in the mess hall, reacting to some foul piano playing––he shows a marvelous capacity for phrasing plus a calm expression that is almost unique in Hollywood films. Miss Reed may mangle some lines (“you certainly are a funny one”) with her attempts at a flat Midwestern accent, but she is an interesting actress whenever Cameraman Burnett Guffey uses a hard light on her somewhat bitter features. Brando must have been the inspiration for Clift’s ability to make certain key lines (“I can soldier with any man,” or “No more’n ordinary right cross”) stick out and seem the most authentic examples of American speech to be heard in films.

Or here he is on Jerry Lewis in That’s My Boy, two years earlier on September 1, 1951, also for The Nation:

The grimmest phenomenon since Dagmar has been the fabulous nationwide success of Jerry Lewis’s sub-adolescent, masochistic mugging. Lewis has parlayed his apish physiognomy, rickety body, frenzied lack of coordination, paralyzing brashness, and limitless capacity for self-degradation into a gold mine for himself and the mannered crooner named Dean Martin who, draped artistically from a mike, serves as his ultra-suave straight man. When Jerry fakes swallowing a distasteful pill, twiddles “timid” fingers, whines, or walks “like Frankenstein,” his sullen narcissistic insistence suggests that he would sandbag anyone who tried to keep him from the limelight. Lewis is a type I hoped to have left behind when I short-sheeted my last cot at Camp Kennekreplach. But today’s bobby-soxers are rendered apoplectic by such Yahoo antics, a fact that can only be depressing for anyone reared on comedians like Valentino, Norma Shearer, Lewis Stone, Gregory Peck, Greer Garson, Elizabeth Taylor, or Vincent Impellitteri.

Last, listen to the opening of his review of The Best Years of Our Lives for The New Republic, December 2, 1946:

For an extremely sensitive and poignant study of life like your own, carrying constantly threatening overtones during this early stage of postwar readjustment, it would be worth your while to see “The Best Years of Our Lives,” even at the present inflated postwar prices.

The sparkling travelogue opening shows three jittery veterans flying home to up-and-at-’em Boone City, a flourishing elm-covered metropolis patterned after Cincinnati. They are too uneasy about entering their homes as strangers to eat up the scenery. The chesty, down-to-earth sailor (Harold Russell), whose lack of sophistication and affectation furnishes a striking contrast to his two chums, is hypersensitive about his artificial hands and is afraid his girl (Cathy O’Donnell) will marry him out of pity rather than love; the sergeant (Fredric March), whose superiority rests in his being old and experienced, a survivor of the infantry and before that a successful banker and father, feels he has changed too much for his old job and his family; the bombardier (Dana Andrews), who has about him that most-likely-to-succeed look of the Air Forces, got married on the run during training and hardly knows what to anticipate.

Despite all the journalistic nimbleness and surprises inside these sentences, or the manifold tonal differences from the famous essays of Negative Space, you still witness emblematic Farber strokes in these brief early extracts from The New Republic and The Nation. Observe throughout the stubborn, graphic detailing (“the real hero,” he proposed in “Underground Films,” is “the small detail”) as he tabs various personality- revealing gestures: Sinatra, for instance, “reacting to some foul piano playing,” or Dean Martin “draped artistically from a mike.” Farber’s later commemoration of the “natural dialogue” and “male truth” of action films is a recasting of his appreciation here of Montgomery Clift’s “authentic . . . American speech” in From Here to Eternity. Note too the distinctive seesaws of contrary adjectives and nouns––“grimmest,” “fabulous,” “success,” “masochistic mugging”––and the bouncy slang, “up-and-at-’em,” “sandbag anyone,” or “short-sheeted my last cot.” Topical allusions (the blonde model-actress Dagmar graced the cover of Life the previous July) bump against deadpan, likely fictive citations (“Camp Kennekreplach”), much as that initial reference to Brando dangles, a tease, nearly a non sequitur, even after Farber ostensibly resolves it later in the paragraph. Observe especially that signature Farber list of “comedians” that concludes the Jerry Lewis swipe. Valentino, Gregory Peck, Elizabeth Taylor . . . all comedians? The final name belongs to the then-mayor of New York City, Vincent Impellitteri, aka “Impy,” appended to the litany––I’m guessing––as much for his Tammany Hall affiliations and betrayals as for his public welcoming a few weeks earlier of Martin and Lewis to the Paramount Theater on Broadway.

By his “Underground Films” essay of 1957 Farber would flip over his fiesta for Sinatra and From Here to Eternity, the crooner-turned-actor by then evincing only “private scene-chewing,” and you will uncover in the New Republic and Nation columns analogous complications for his later appraisals of Preston Sturges, John Huston, and Gene Kelly. Farber initiated his career as an art and film critic at The New Republic early in 1942, and co-wrote his last essay with his wife, Patricia Patterson, in 1977; that’s a 35- year arc. Of the original 281 pages of Negative Space,roughly 230 emanate from a 12-year stretch, 1957 through 1969, directly prior to the book. Farber titled a magnificent 1981 “auteur” painting, rooted in the films of William Wellman, Roads and Tracks. Farber on Film can advance alternate routes—other roads, other tracks—into, through, and around Farber’s familiar trajectory as a critic and writer.

Above: Manny Farber's painting Road and Tracks (1981).

Occasionally in interviews he will present himself as a sort of natural critic, steeped in opinions and argumentative strategies. “An important fact of my childhood was that I was surrounded by two brothers who were awfully smart, and very good at debating,” Farber once told me. “We averaged three to four movies a week, sometimes with my uncle Jake. There was a good library, and in the seventh grade I started to go there and read movie criticism in magazines. I would analyze it and study it.” Then, at other moments, Farber suggests that ultimately only words matter to him. “When I’m writing I’m usually trying for a language. I have tactics, and I know the sound I want, and it doesn’t read like orthodox criticism. What I’m trying for was a language that holds you, that keeps a person reading and following me, following language rather than following criticism. I loved the construction involved in criticism.”

Manny Farber was born on February 20, 1917, in Douglas, Arizona, his house at 1101 Eighth Street just five blocks from the Mexican border. His parents ran a clothing store, La California Dry Goods, on G Street, Main Street in Douglas, across from the Lyric Theatre and also near the Grand Theatre. He followed his older brothers Leslie and David to Douglas High School, where he played football and tennis, wrote about sports, and contributed drawings of Mickey Mouse to the school yearbook, The Copper Kettle. After his family moved to Vallejo, California, and then to Berkeley, Farber enrolled in the University of California, Berkeley, for his freshman year, before transferring to Stanford. At Berkeley, Farber covered sports for The Daily Californian, his earliest signed article, a spirited forecast of the upcoming track and field season, appearing on January 25, 1935, under the headline bear weight men rated as strong group. As he concluded his journalistic debut:

Further joy was added to the track outlook with the announcement that big Glen Randall, Little Meet record holder, will again heave the discus this spring. Seriously hurt in an automobile accident last October, Randall is again ready to hurl the platter out to the 150 foot line. Aiding him in this event is Warren Wood, a potential first place winner but an erratic performer.

Farber often claimed sportswriters as an influence on his criticism, and routinely injected sports metaphors into his columns, surprisingly for art as much as film. Richard Pousette-Dart, he suggested in The Nation (October 13,1951), “is something close to the Bobby Thomson of the spontaneity boys,” while Ferdinand Leger, he contended in The Magazine of Art (November 1942), “reminds me of a pitcher who can throw nothing but fast balls, and his fast balls so fast you can’t see them.” Reviewing sports-film features, he stressed that the games be represented as convincingly as any other profession. On Gary Cooper as Lou Gehrig in Pride of the Yankees:

No matter that Gary doesn’t like baseball, is right-handed, lazy and tall-skinny, whereas Gehrig was left-handed, hard-working to the point of compulsion, and his one leg was the size of two of Gary’s. So they taught him to throw left-handed, but they could never teach him to throw with any muscles but the ones in his arms, like a woman, nor could they make his long legs run differently from those of someone trying to run with a plate between his knees, nor could they move his body with his bat swing.

All of which meant cutting the baseball action to a minimum––montage shots mostly from long distance up in the press box, and the picture was shot to hell right there. (New Republic, July 27, 1942)

After taking drawing classes at Stanford, Farber enrolled at the California School of Fine Arts, and then at the Rudolph Schaefer School of Design. Around San Francisco, he supported himself as a carpenter, until he joined his brother Leslie in Washington, in 1939, and then in New York, in 1942. Both Leslie and David Farber found callings as psychiatrists; Leslie, notably, was the author of The Ways of the Will: Essays Toward a Psychology and Psychopathology of Will (1966), and Lying, Despair, Jealousy, Envy, Sex, Suicide, and the Good Life (1976). Leslie Farber’s psychoanalytic essays track curious affinities with his brother’s film writings––Leslie’s “distrust” for “any psychological doctrine . . . [which] requires the repeated fancying-up of some item of experience––memory, dream, feeling, what have you––to give it an epistemological razzle-dazzle it couldn’t manage on its own” inevitably recalls the “wet towels of artiness and significance” of white elephant art. Overall his brothers’ immersion in the human inner life appears to have prompted Manny’s contempt for psychology, whether on screen or in his own writing. “I moved as far away as I could from what Les and David were doing,” Farber told me. “My whole life, the writing, was always in opposition to Leslie’s domain, his involvement with psychology, brain power, etc. But there was never any quarreling between brothers. It was just competing, that’s all.” Under the title “Paranoia Unlimited,” (New Republic, November 25, 1946), Farber joked:

In answer to the demand for movies that make you suspect psychopathological goings-on in everyone from friend to family dog (yesterday’s heroes killed Indians, today’s are associated one way or another with psychiatry), MGM has reissued a pokey oldie called “Rage in Heaven.” This relic starts at a lonely asylum with a comic-opera escape by an unidentified inmate (Robert Montgomery) who is known to be paranoid only by the asylum doctor (Oscar Homolka, who gives an embarrassing rendition of a Katzenjammer psychiatrist).

Still, as with football or baseball, he would notice the “fairly accurate” rendition of an analyst’s questions in Hitchcock’s Spellbound, even as he dismissed the Dali dream as “a pallid business of papier-mâché and modern show-window designing” (New Republic, December 3, 1945).

With a characteristic mix of the flip and the canny, Farber bamboozled his way into The New Republic with a “smart-aleck” letter to editor Bruce Bliven, indicating that “I could do the job better than anyone else who was doing it.” His earliest art column appeared on February 2, 1942, a review of the MOMA show, “Americans 1942–– Eighteen Artists from Nine States,” that featured a postage stamp–sized sketch by Farber of artist John Marin. His next art column two weeks later delineated the face of Max Weber, then in a Whitney Museum watercolor exhibition. “I planned to do a drawing to go along with every article,” Farber told me, “but I just couldn’t keep up.” After Otis Ferguson enlisted in the Merchant Marine as a seaman, Farber took over the film column, publishing on March 23 a round-up review of three war films, including To Be or Not to Be. As an art critic, Farber sounded like Farber from his premiere column, accenting “action” and “flexibility,” denouncing “stylization” and “dogma.” With movies, he took longer––perhaps also piling on at first too many films at once for a short review; not until May would he learn to fixate on a single film and wrap up the others in a codicillary paragraph.

As I suggested at the outset, Farber on Film can be read for both continuities and departures, especially toward or away from the key essays of Negative Space. Looking back from the vistas of “The Gimp,” “Underground Films,” and especially “White Elephant Art vs. Termite Art,” Farber can be viewed as implacably progressing into his galvanizing notions. In “The Gimp,” for instance, published in Commentary in 1952, he imagined a “gimmick,” a device with a string that a director might jerk any time he wished to insert some “art” into a film. As far back as 1945 he was propounding a sort of protean mask for the same purposes:

A device will soon be invented in Hollywood that will fulfill completely the producers’ desire to please every person in the movie-going public. The device will be shaped like a silo and worn over the face, and be designed for those people who sit in movies expecting to witness art. It will automatically remove from any movie photographic gloss, excess shadows, and smoothness, makeup from actors’ faces, the sound track and every third and fifth frame from the film in the interest of giving the movie cutting rhythm. It will jiggle the movie to give it more movement (also giving the acting a dance-like quality). To please those people who want complete fidelity to life it will put perspiration and flies on actors’ faces, dirt under their fingernails, wet the armpits of men’s shirts and scratch, flake and wear down the decor. It comes complete with the final amazing chase sequence from “Intolerance” and the scene from “The Birth of a Nation” in which the Little Sister decorates her ragged dress with wads of cotton, which it inserts whenever somebody is about to conduct an all-girl symphony. The gadget also does away with all audience noise. (New Republic, August 20, 1945)

Throughout the 1940s and early 1950s Farber memorialized the 42ndStreet itch-house hippodromes he would tag “caves” in his 1957 essay “Underground Films.” This, from 1943:

Who builds movie theatres? If you seek the men’s room you vanish practically away from this world, always in a downward direction. It is conceivable that the men’s room is on its way out. At the theatre called the Rialto in New York the men’s room is so far down it somehow connects with the subway: I heard a little boy, who came dashing up to his father, say, “Daddy! I saw the subway!” The father went down to see for himself. Another place that lets patrons slip through its fingers is the theatre in Greenwich Village where the men’s room is outside altogether. (New Republic, June 7, 1943)

That same year he observed of the action films he would eventually ticket as underground: “It is an interesting Hollywood phenomenon that the tough movie is about the only kind to examine the character’s actions straight and without glamor” (New Republic, January 11, 1943).

The dynamics of white elephant art were fully in place at least nine years, maybe even more than a decade before Farber’s 1962 essay “White Elephant Art vs. Termite Art.” He attached the word “elephantine” to the concept for an October 17, 1953, Nation column, and defined it recognizably in his recapitulation the previous January of his ten best films. “The only way to pull the vast sprawl of 1952 films together is to throw most of them in a pile bearing the label ‘movies that failed through exploiting middle-brow attitudes about what makes a good movie.’ . . . It is difficult to say whether I liked or disliked a number of films that will appear on most other lists, since it was usually a case of being impressed with classy craftsmanship and bored by watching it pander to some popular notion about what makes an artistic wow” (Nation, January 17, 1953). But white elephant art loops back through the years, accruing linkages and implications. A 1952 review of Carriepositions underground films against white elephants without naming either:

Hollywood films were once in the hands of non-intellectuals who achieved, at best, the truth of American life and the excitement of American movement in simple-minded action stories. Around 1940 a swarm of bright locusts from the Broadway theaters and radio stations descended on the studios and won Hollywood away from the innocent, rough-and-ready directors of action films. The big thing that happened was that a sort of intellectual whose eyes had been trained on the crowded, bound-in terrain of Times Square and whose brain had been sharpened on left-wing letters of the thirties, swerved Hollywood story-telling toward fragmented, symbol-charged drama, closely viewed, erratically acted, and deviously given to sniping at their own society. What Welles, Kanin, Sturges, and Huston did to the American film is evident in the screen version of Dreiser’s “Sister Carrie,” which is less important for its story than for the grim social comment underscoring every shot. (Nation, May 17, 1952)

Such fledgling evocations of white elephant art render explicit, as his 1962 essay never would, the intimation that Farber, who as a carpenter in San Francisco tried to join the Communist Party, was specifically dethroning the vulgarities and hypocrisy of liberal New Deal Hollywood as much as any other inadvertently comic bourgeois correctness. As he wrote of Come Back, Little Sheba, “You will half-enjoy the film, but its realism is more effective than convincing, and it tends to reiterate the twisted sentimentality of left-wing writing that tries to be very sympathetic toward little people while breaking its back to show them as hopelessly vulgar, shallow, and unhappy” (Nation, November 8, 1952). Other reviews connect elephantitis with films that would be dubbed noir (Murder, My Sweet; Farewell, My Lovely; Laura; and Double Indemnity), with European films (Miracle in Milan), Japanese films (Rashomon), Oscar aspirants (Mrs. Miniver), and Disney cartoons (Bambi). As a category, if not a punchline, white elephant art was vital to Farber’s thinking about movies and paintings from his first months at The New Republic.

Termite art of course is everywhere in his New Republic and Nation columns, though fascinatingly never via the urgent termite metaphors (“tunneling,” “burrowed into,” “excavations,” “veining,” “nibbles away,”) that stitch together both “Underground Films” and “White Elephant Art vs. Termite Art.” You twig termite art in Farber’s 1940s valentines to B-movies and B-directors, his early assertion that “there is not a good story film without what is called the documentary technique,” (New Republic, July 12, 1943), his recurrent application of the adjectives “honest” and “accurate” for his highest praise, his emphasis on scrupulous history in allegedly historical movies, and in phrases like “the details of ordinary activity” (New Republic, February 8, 1943), and “actual life in actual settings” (New Republic, March 13, 1944). His dazzling invocation of late-night New York radio talk-jocks for The American Mercury, “Seers for the Sleepless,” similarly would italicize their fidelity to the “sounds of real life.”

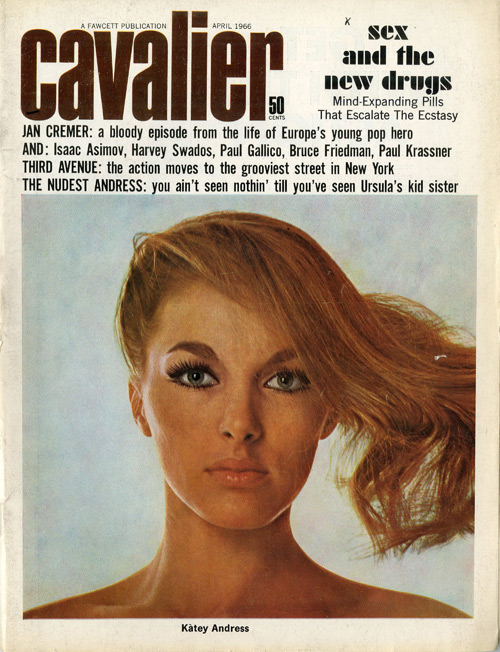

These columns also comprise a sort of anthology of the infinite ways of scaffolding a mixed review. Early and late, in his writing and for his paintings, Farber would demand multiple perspectives. As he ultimately lamented about popular arts criticism, “Every review tends to become a monolithic putdown or rave” (Cavalier, June 1966). Here he leads off a 1942 New Republic art column being wisecracking and caustic toward Thomas Hart Benton:

A bush-league ball player never gets beyond the Three Eye League, but a bush-league painter can be known coast to coast, especially if he has the marvelous flair for publicity that is Benton’s. When Mr. B paints a picture, almost like magic the presses start rolling, cameras clicking, and before you know it everyone in East Orange is talking about Tom’s latest painting.

Yet, by the next paragraph he is already back-pedaling––he admits that “Benton has painted war as it actually is” and concludes, “Mr. Benton may be strictly a lightweight as a painter, but he is nevertheless honest and wise enough to paint the war as war, and not as pattycake pattycake” (April 20, 1942). By 1945, reviewing The Clock, Farber could insinuate all his contrary responses into just one paragraph:

The movie is dominated by the desire to be neatly pleasant and pretty, and truthful only so far as will not basically disturb the neatness, pleasantness and prettiness. The furlough without an empty, disappointing, lonely, distasteful or fearful moment is as hard to believe as is the portrait of New Yorkers as relaxed, daisy-faced, accommodating people who send champagne to soldiers in restaurants. Most of the story is the sensation-filled, laugh-hungry, coincidence-ridden affair a gag writer would invent, and probably the hardest fact to swallow is the film’s inability to show anything in its lovers that might indicate that their marriage would ever turn out to be any less blissful than their two-day courtship. Mainly because of the direction of Vincente Minelli, “The Clock,” though, is riddled as few movies are with carefully, skillfully used intelligence and love for people and for movie making, and is made with a more flexible and original use of the medium than any other recent film. (New Republic, May 21, 1945)

By 1953 Farber would require just a single mixed sentence. “Stalag 17 is a crude, cliché-ridden glimpse of a Nazi prison camp that I hated to see end” (Nation, July 25).

Ultimately, though, for all its intersections with Negative Space, Farber on Film inscribes alternatives rather than correlatives. For the first time it’s possible to shadow Farber as a professional chronicler of new films, and he emerges as thoughtful and skillful precisely where his reputation predicts he might be careless––actors, plots, judgments, even annual best lists. Alongside his reviews, he also wrote an alluring motley of “think pieces” on such topics as “The Hero,” “Movies in Wartime,” “Theatrical Movies,” independent film trends, screwball comedies, documentaries, newsreels, hidden cameras, censorship, 3-D, and television comics. Farber moonlighted away from both his beats–– smart, resonant essays on Russel Wright dinnerware, Knoll furniture, jazz, and Pigmeat Markham. Part memoir, part prescient anatomy of the exaltation of talk radio in American experience over the coming decades, part midnight hallucination of “disembodied” voices, “Seers for the Sleepless” approaches the everyday visionary art of his Greenwich Village friends Weldon Kees and Isaac Rosenfeld. His early pieces during World War II routinely entail vivid social history, and Farber always proved alert to racial affronts and offenses in Hollywood films. From 1942: “Behind the romantic distortion of Negro life in ‘Tales of Manhattan’ is a discrimination as old as Hollywood” (New Republic, October 12). Or 1949: “The benevolent writers––working in studios where as far as I know there are no colored directors, writers, or cameramen––so far have placed their Negroes in almost unprejudiced situations, presented only one type of pleasant, well-adjusted individual, and given him a superior job in a white society” (Nation, July 30).

As a regular reviewer, Farber also turns out to be funnier than you’d calculate, not just caustic or cranky, but witty. Early on he complained about overcrowded museum exhibitions of two, maybe three hundred paintings. “Something like it would be reading War and Peace, two short stories and a scientific journal in one sitting” (New Republic, February 16, 1942). “All kinds of hardships have to be endured in wartime,” Farber confessed. “Some of them could be avoided. One of these is the war poster that plays hide-and-seek with art and our times. I don’t think the lack of aesthetics is anything to carp about at this stage, but I do think they ought to mention the war above a whisper” (New Republic, March 16, 1942). Reviewing a three-and-a-half-million-dollar film about Woodrow Wilson called Darryl F. Zanuck’s Wilson in Technicolor, he observed, “For several reasons, one being that Wilson had a ‘nice’ tenor voice, there are 87 songs blared or sung in the picture from 1 to 12 times and as though the audience left its ears in the cloak room: come in at any time and you will think ‘Zanuck’s Sousa’ is being shown” (New Republic, August 14, 1944). Still, Farber could also sound caustic and cranky–– “The closest movie equivalents to having a knife slowly turned in a wound for two hours are ‘Tender Comrade’ and ‘The Story of Dr. Wassell’” (New Republic, June 26, 1944).

Once Farber quit New York and moved to San Diego with Patricia in the fall of 1970, he abandoned criticism for painting and teaching. Although he wouldn’t entirely stop writing until 1977, Farber ended––at least he set in motion the steps that would lead him to end––his three-and-a-half decade stint as a critic as whimsically (or craftily) as he had started it with that wise-guy letter to The New Republic. During a drunken dinner––and Manny rarely drank––after a 1969 show of his monumental abstract paintings on collaged paper sponsored by the O.K. Harris Gallery, he found himself talking to another artist, Don Lewallen, a UC San Diego professor in painting, on leave in Manhattan and wishing to stay. Somehow, by the end of the night, Farber had traded his loft on Warren Street for the professor’s job at UCSD.

He joined the Visual Arts faculty, teaching small painting classes and large film lecture courses. “It was hell from the first moment to the last,” Farber recounted in an interview. “We came for me to teach painting, which was fine. I’d been doing that once a week in New York. I was very comfortable, and it was a nice thing to do. But someone had the idea that I teach film appreciation, since I’d been writing criticism. And it seemed OK. We didn’t realize it would become such an overwhelming job. The classes in film would have 300 students, instead of the 15 you’d have in a painting and drawing class. I was swamped.” The UCSD faculty mixed artists, poets, critics, and art historians, and included David Antin, Jehanne Teilhet, Michael Todd, Ellen van Fleet, Newton Harrison, Gary Hudson, Allan Kaprow, and eventually J. P. Gorin.

Farber taught a “History of Film” class—one opening week he screened The Musketeers of Pig Alley, Fantômas, A Romance of Happy Valley, and True Heart Susie, while his week three spanned Sunrise, Underworld, Scarface, and Spanky. He also taught “Third World Films” and “Films in Social Context” and created a class in “Radical Form” called “Hard Look at the Movies” that moved from Godard‑Gorin and Andy Warhol through Fassbinder, Marguerite Duras, Michael Snow, , Jean‑Marie Straub, Alain Resnais, and . “Manny's film classes,” as Duncan Shepherd, later film critic for the San Diego Reader, recalled, “were the stuff of legend, and it seems feeble and formulaic to call him a brilliant, an illuminating, a stimulating, an inspiring teacher. It wasn't necessarily what he had to say (he was prone to shrug off his most searching analysis as ‘gobbledegook’) so much as it was the whole way he went about things, famously showing films in pieces, switching back and forth from one film to another, ranging from Griffith to Godard, Bugs Bunny to Yasujiro Ozu, talking over them with or without sound, running them backward through the projector, mixing in slides of paintings, sketching out compositions on the blackboard, the better to assist students in seeing what was in front of their faces, to wean them from Plot, Story, What Happens Next, and to disabuse them of the absurd notion that a film is all of a piece, all on a level, quantifiable, rankable, fileable. He could seldom be bothered with movie trivia, inside information, behind-the-scenes piffle, technical shoptalk, was often offhand about the basic facts of names and dates, was unconcerned with Classics, Masterpieces, Seminal Works, Historical Landmarks. It was always about looking and seeing.”

Farber’s exams and quizzes demanded his students see all the films, and then remember everything they saw and heard––“Describe the framing (composition) and use of people in the following: a. McCabe and Mrs. Miller; b. Walkabout; c. Fear Eats the Soul; d. Mean Streets”; “Identify the movie in which this unforgettable scriptwriting appears….” He directed pitiless essay questions––“MOUCHETTE emphasizes the existence of contradictory impulses succeeding one another (more rapidly than is admitted in our culture). Describe this transiency in either the stream edge fight between poacher and warden or the rape scene between Arsene and Mouchette (camera, framing, etc.). BROKEN BLOSSOMS is gravely different; using any of the scenes between Lucy and Battling, show how these two characters are locked into a single emotion in relation to each other.” (This was one question.) Sometimes he asked for storyboards:

Draw one frame from each of the following scenes:

a. the dancehall scene in “Musketeers” when Lillian Gish is first introduced to the gangsters.

b. The subway scene in “Fantômas” with the detective and the woman he is shadowing in an otherwise empty car.

c. The scarecrow scene with Lillian Gish in “A Romance of Happy Valley.”

Indicate in words alongside each frame how close the actors are to the screen surface, the depth of space between figures and background, the flow of action if there is any.

Farber retired from teaching in 1987.

Above: Manny Farber's painting Birthplace Douglas Arizona (1978).

Farber on Film Introduction: Part 1 (Other Roads, Other Tracks) | Part 2 (Farber and Negative Space) | Part 3 (Farber Before Negative Space) | Part 4 (After Negative Space)