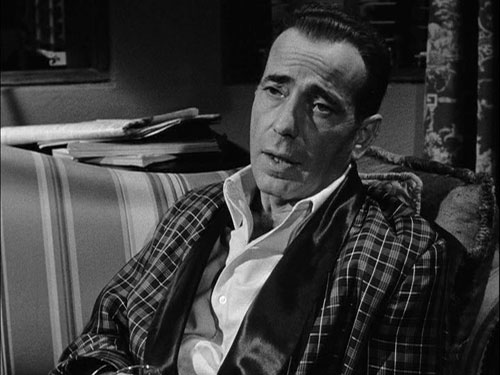

Above: Gloria Grahame and Humphrey Bogart.

I was born when she kissed me, I died when she left me, I lived a few weeks when she loved me.

In a Lonely Place (1950) is a film noir that doesn’t care about the murder. It barely has time to pay attention to whether washed-up screenwriter Dixon Steele (Humphrey Bogart) killed a hat-check girl he took back to his place who was going to tell him the story of a book he’s about to adapt. Far more terrifying to express is what that formulaic plot uncovers: the emotional violence a couple can inflict upon each other. For that is what the relationship between Dix and his neighbor, Laurel Gray (Gloria Grahame) is all about. It is unlikely Bogart was ever more frightening, and he doesn’t even touch a gun. Nor was he ever so pathetic, so vulnerable, so damaged. His Dixon Steele lashes out at the universe for the success it took from him, and for the wisdom and sensitivity it refuses to recognize—primarily because he is so quick to temper with those he can’t stand, which is most of the world. In other words, Dix is Nicholas Ray.

Maybe even more impressive is the bringing to life of Gloria Grahame. A wooden and catty actress in her 40s work, In a Lonely Place is her greatest performance, rivaled only by her turn in Minnelli’s The Cobweb. Laurel Gray is calm, composed, collected. Grahame jams her hands in the pockets of her skirt, or knowingly half-smiles at Bogart in a manner suggestive of someone who is as comfortable as she is controlled. Every facial movement is precise and meaningful. Laurel Gray is a failed actress, and like all great Ray protagonists, acutely aware of her own failures. Like one group of them—Vienna in Johnny Guitar, Jeff McCloud in The Lusty Men—she has wearily accepted what has befallen her. She therefore stands toe to toe with Dix’s bipolarity and his potential alcoholism. (Note how Ray positions Grahame above Bogart, dominating him, which inverts an earlier shot.) Only when Dix’s inner demons bring him to almost kill someone that her self-control—and her parity with Dix—fissures, and she begins to wonder if he really might be capable of murder.

Dix is an outsider, a man not meant to travel in the comforts of normal society. Unlike Ray’s other protagonists, however, his individuality destroys him. Rather than define his strengths, that marginalization is his greatest weakness. He and Laurel’s loneliness is quelled by their union for only 16 of the film’s 93-minute running time. Their isolation is too powerful to keep them together. In a way, from how she keeps Dix at a distance, and how she faintly wishes their love could have lasted, Laurel knows their fate from the beginning.

***

When he was hanging around the production of Elia Kazan's A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, Ray spent a lot of time with the editors. “I’d bring them cartoons from the funny papers and say, ‘Why don’t we edit this way? The hell with conventionality.’” This is brought to bear in several sequences. Near the beginning, as Mildred Atkinson (Martha Stewart) prattles on about the book Dix is dreading to adapt, she tells the story directly to the camera, which conflates Dix and the audience. Suddenly, we cut to Dix, who is looking off to the side in a standard shot/reverse-shot pattern. Juxtaposing the two causes the audience to identify with and be alienated from Dix, a feeling we carry throughout the film thanks to his schizoid behavior.

Toward the end, when Laurel confesses her fears about Dix to her friend Sylvia (Jeff Donnell), Ray breaks the axis when cutting from one close-up to another. Tension from spatial disorientation is established, and we fear for Laurel even more strongly.

***

The climax is more brutal than if Dix had actually murdered anyone. He begs Laurel to marry him. She tries to escape. He finds out. He almost strangles her to death. The police call. Dix has been cleared of the murder—not that it matters much. Long, silent, haggard visions of a love gone wrong fill the screen. He staggers out into the street, he and Laurel returning to the isolation they discovered they could never escape.

***

Undiscussed motifs: Bars, grates, and other cage-like objects; filming behind characters’ heads, their faces out of view; engaging deep space not only visually but aurally, registering the distance of the recorded voice. These appear not only in In a Lonely Place but in so many of Ray’s films that they will be discussed in future entries.

***

Homes for Strangers: The Cinema of Nicholas Ray is an on-going series of articles covering the 2009 retrospective on Nicholas Ray, running from July 17th to August 6th—with a special bonus on August 16th & 17th at the Anthology Film Archives—at New York's Film Forum.