Raymond Griffith, silent comedian, has fallen into such neglect as to be virtually erased from screen history, it seems. None of his comedy appears to be available on any commercial format, nor ever has been. And much of his work is thought lost forever.

This would be sad even if Griffith were just one of those mustachioed little men falling over in Mack Sennett shorts, filling out a Keystone Kops paddy-wagon or slipping on a banana peal. What makes it tragic is that he was a unique, subtle and subversive talent, not notably like any of his famous contemporaries.

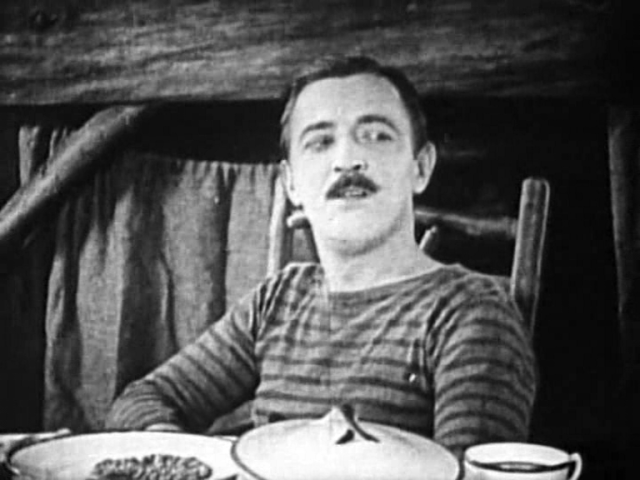

How to describe him? Eschewing the grotesquerie of the typical clown, he was small, trimly-built, and wore a neat, normal mustache. He was almost good-looking, a certain heaviness about the jowls giving him a debauched look which he exploited to his advantage. He had a variety of smiles, most of them a touch insincere: the lip curled while the eyes remained appraising. And yet, there's real charm.

Griffith's costume, once he became a star, was dapper: top hat and tails, sometimes with a cloak. In Hands Up! (1926), set in the west, he has the look of a riverboat gambler. Hands Up! is known for being the other Civil War comedy released the year Buster Keaton gave us The General, the one which was a hit while Keaton's film sank, the one which was cheerfully accepted by the critics while Keaton's was cruelly dismissed. Of course, by the 1960s, with Keaton's rediscovery, it became fashionable to say that the world made a serious mistake in 1926, which indeed is true. But Griffith's film is very good too. Not an immortal classic, but a zestful and inventive caper that looks forward to the manic exuberance of the Warner Bros. cartoons.

It's fitting that Griffith plays a spy in the film: it suits his shifty, ingratiating persona. The plot follows his attempts to frustrate the delivery of a batch of freshly-struck gold intended to help the Northern cause, and turns on his quicksilver lies, disguises and deceits. When a firing squad is distracted from shooting him for just a few minutes, they find themselves blowing holes in a stone wall on which he has painted a convincing likeness of himself, a moment of pure Road Runner. He not only inveigles his way into the affections of his natural enemy, sheriff Mack Swain, but successfully woos both the man's nubile daughters, and elopes with them, after being inspired by a cameo appearance by Brigham Young and his nineteen wives. Caught red-handed at his sinister spycraft, he infuriates his opponents by smirking devilishly and taking a pinch of snuff—

—before throwing the whole box of powder in their faces, ducking under a stagecoach and running for it as they sneeze themselves silly.

In Tod Browning's White Tiger (1923), a "thieves fall out" yarn, Griffith had a rare straight role. An unusually subdued tale for Browning, even if the plot involves a fake mechanical chess player (operated by a concealed Griffith), waxworks, burglarious conspiracy and Argentine ant poison. All the actors, led by Griffith's suave example, are wonderfully restrained, from the hard-boiled Priscilla Dean to the remarkably muted Wallace Beery. Griffith, regardless of the film's air of perverse melodrama, with its barely concealed incestuous and murderous passions, is very funny.

Above: The marvelous mechanical chess-player at work, with Raymond Griffith working the toggles from within.

Playing crooks was very much in Griffith's line: Paths to Paradise (1925) sees him as a con-artist and safe-cracker. The movie begins with a classic set of reversals, in which Betty Compson's gang first fleece Griffith of his bulging wallet's contents, then are forced to give up all their loot to him when he reveals himself to be an undercover detective, then discover he's a fellow crook. Compson was an interesting performer too: best known for Sternberg's The Docks of New York (1928) she had her own production company and exercised unusual control over her career. As with Griffith, several of her most important films are now considered lost.

Paths to Paradise itself is minus an ending, although the hour that remains is so good that it fully satisfies, even leaving one somewhat giddy and exhausted by the plot's manic turning and the pace of the action. Griffith's character is the ultimate confidence man: having no name of his own, it seems, he gives a different pseudonym at each introduction, and always responds to the paging in hotel lobbies, regardless of who is being asked for. "One never knows what will happen." At the point where the film runs out, he's just escaped to Mexico with Compson and a purloined necklace, in perhaps the most manic chase of the silent era. In the segment now missing, Compson changes her mind and decides to return the jewels, necessitating an even faster race back across the border: Griffith, ever the passive human flotsam, accepts honesty as cheerfully as he'd embraced criminality.

Both Hands Up! and Paths to Paradise were directed by Clarence Badger, showing far more flair than evidenced in Teddy at the Throttle, reviewed here a few weeks back. Badger also made the fun Clara Bow vehicle It (1927), which is what he's chiefly remembered for, but in fact, Paths strikes me as considerably superior to It and may be one of the best ever examples of cinematic farce, an extremely difficult form.

"No emotion" was Griffith's rule of acting, a strange one given his remarkable expressiveness. But it's certainly true that he makes no claim on the audience's emotions. While Chaplin asks us for our sympathy, and Keaton wants to get it without asking, Griffith remains marvelously indifferent to all that, just playing the scenes he's given. His very aloofness from us may win our respect, but he couldn't be bothered one way or the other. Did any star ever flourish, however briefly, precisely because of his indifference to the audience?

His acting career more or less ended with sound, and for a striking reason: Griffith lost his voice due to childhood illness and overstrain. One night, on stage, he was supposed to scream, and his voice just cracked. From then on, he couldn't speak above a whisper, an insuperable obstacle for an actor in the early days of talkies. He did continue briefly as a writer, his experience as a Sennett gagman standing him in good stead, and as a producer on into the fifties. He was actually one of the founders of Twentieth Century Fox.

There's one last post-stardom movie appearance, and it's one more people have seen than than any of his star vehicles. In All Quiet on the Western Front (1930), he plays a mortally wounded French soldier who shares a foxhole with the hero. Since the only vocalization required was tortured breathing, Griffith's handicap was more of an aid than a problem. In his last moment on screen, he signifies death by opening, rather than closing, his heavy-lidded eyes, and slightly curls his upper lip in a mirthless grin.

***

The Forgotten is a regular Thursday column by David Cairns, author of Shadowplay.