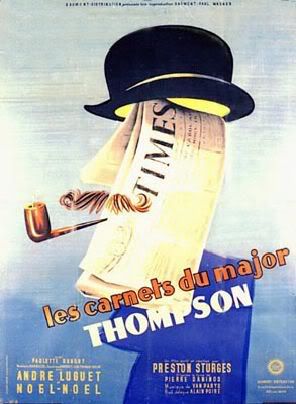

I'd long wanted to see Preston Sturges's last film, Les carnets du Major Thompson, AKA The Diaries of Major Thompson, AKA The French, They Are a Funny Race, even though I knew the experience was unlikely to be an especially edifying one. A movie described as "almost defiantly unfunny" doesn't inspire much confidence, and the best anybody had ever found to say about it was that it was not quite as awful as all that.

I've now seen the film, and I can second the view that it's not quite as awful as all that, but I can't go any further. The interesting question is whether the movie's failings are entirely the fault of Preston Sturges. His career—four years of highly productive directing work at Paramount studios, during which he made eight films which could fairly be called masterpieces of comedy, bracketed on one side by several years of screenwriting for directors like William Wyler and Mitchell Leisen, and on the other by spells with Howard Hughes and 20th Century Fox, followed by his one European production—has so long been considered that of a falling star that the easy assumption is that he was a burned-out, alcoholic wreck in his latter years and no return to form could ever have been expected. But the story isn't so simple.

The film thought to have begun the slide is The Great Moment, which was recut by Paramount to lessen its serious points, which couldn't very well work in an essentially tragic story about a great benefactor of mankind who died in poverty, reviled by the people he'd tried to help (an unwittingly prophetic self-portrait, perhaps). Critics are quick to denounce the movie as tonally confused and ultimately unsuccessful, but it's not Sturges's film they're seeing, and he pulled off dizzying tonal shifts in many of his earlier films. This flop may not be laid at his door.

Of the post-Paramount movies, Unfaithfully Yours now comes across as a mature masterpiece, with even the protracted and painful slapstick of the third act having some perverse value: it's not exactly funny, to most tastes, but its repetitive, agonizingly slow, frustratingly clumsy rigmarole may be the cinema's best evocation of the mental collapse wrought by sexual jealousy upon a sensitive mind. That film now has plenty of defenders, and it's clearly another autobiographical work, the story of a temperamental artist shipwrecked on the shoals of his own neurosis.

The Beautiful Blonde from Bashful Bend is more problematic, and very much a work-for-hire Sturges embarked upon purely to win the favor of Darryl Zanuck. It's hampered by too much slapstick, too little heart, and much too much Hugh Herbert, a terrible burden for any film with pretensions to humorousness. But bits of it are very funny indeed, and it's interesting to see Sturges working in color, in the wild west setting, and with Betty Grable. Also, the very first scene, in which a tiny, doll-like, impossibly cute little girl blasts bottles to pieces with a colt six-shooter, has more blasphemous shock value, and say more about America's love of small-arms fire, than the whole of Kick Ass.

And The Sin of Harold Diddlebock is excellent, even if it was a troubled shoot: Harold Lloyd and Preston Sturges could not agree on whether visual or verbal wit should predominate, and the attempt to recreate a classic Lloydian hi-rise suspense sequence in the studio, with rear projection, falls somewhat flat. Although I like the way in this movie Harold gets post-traumatic stress from the incident and wakes up screaming the day after.

So really the decline looks like it's based more on circumstance than on any reduction in Sturges's ability to craft boffo laff sequences. And then, six years later, we get his last film.

If he'd been deprived of the stability of a comfortable and supportive studio setting on his later Hollywood films, Sturges had covered the problem nicely, but on this film he is cruelly deprived of everything. He doesn't have American stars, and he doesn't have his essential stock company of grizzled veterans to fill the background: no Eric Blore, no Torben Mayer, no Bill Demarest and certainly no Franklin Pangborn. Little effort seems to have been made to replace these irreplaceable fizzogs with continental equivalents, should such animals exist. The lack of Hollywood technicians need not have been so damaging, but the lack of the U.S. idiom is seriously problematic. Sturges was one of the great poets of American slang, weaving linguistic tapestries of impossibly high-fallutin' prose, punctuated by deflating bursts of vernacular vulgarity. And here he has a retired English major and a bunch of Frenchmen to work with.

To make matters worse, he was required to make his film in both French and English, which posed two problems: writing and casting. Sturges's friend René Clair, for whom he had produced and co-written I Married a Witch, pointed out to him that his French was that of a pre-WWI schoolboy: which was when Sturges learned his French. The supposedly bilingual actors recruited for the movie, Scottish musical comedy star Jack Buchanan (seen in The Band Wagon), and French glamor girl Martine Carol (Lola Montes), spoke each others' languages so badly they couldn't understand each other and missed their cues, thereby fracturing the essential comedy timing. And poor Buchanan was suffering from the cancer of the spine which would eventually kill him.

Nothing is much less funny than spinal cancer. Except this film, standard wisdom will tell you. Like Laurel & Hardy (Utopia) and Buster Keaton (The King of the Champs-Elysee), Sturges seems to have been cut off from the wellspring of his comedy and forced to work with unsuitable collaborators in an unsuitable environment. Little wonder he struggled. Shooting was slightly difficult, since the French studio did not have the facilities Sturges was used to. Between Flops, by James Curtis, reproduces an extract from an interview Sturges gave the BBC: "The system in France is called debrouillard - which means 'now you're in it, get yourself out of it.' Everyone laughs about it, but nothing counts except what you eventually get on the screen." Quite.

Sturges recorded in his unfinished memoir (whose title, The Events Leading Up to My Death, was abandoned when he actually died after drafting the last paragraph) that he wrote a screenplay for his producers using the popular comic newspaper column, The Diaries of Major Thompson, as a springboard for an original story, which he titled Forty Million Frenchmen. In this yarn, the French author of the fictional diaries is accosted by a man claiming to be the actual Major. This Pirandellian conceit would be resolved by the discovery that the so-called "Major Thompson" is a shell-shocked war hero with amnesia, and the author generously grants the unnamed soldier the new identity he desires. This kind of miraculous happy ending, whose unreality is so plain it carries a melancholy tang, is classic Sturges, and the project seemed to promise much.

But then the collected articles about Major Thompson became a best-seller, and the producers politely let Sturges know that they required something more in the style of the column itself. So Sturges was forced to write a new version, in which we see Thompson dictating his essays, and interacting with his wife and his son's nanny, and we see illustrated sequences depicting the content of these popular essays. Which aren't terribly funny.

Robbed of the momentum that an actual story would provide, Sturges understandably flounders. When Buchanan and Carol argue, the film shows signs of animation: Sturges was always great on man-woman stuff, and even though his leading lady is occasionally hard to understand, and the two performers do seem to be in seperate, if distantly related, films, there is some pleasure and even a few laughs, or at any rate audible smiles, to be had. And during the essay sequences, French actor Noël-Noël mimes the role of typical Frenchman, while Buchanan recites the text, a return to the patented form of voice-over "narratage" which Sturges had deployed in The Power and the Glory back in 1933. So that's not devoid of interest, even if it's about as funny as an oil spill.

A couple of terrible errors of judgement do appear, notably a sequence dealing with the death of the Major's first wife, which is neither funny nor tragic, just crassly inappropriate and pointless. Balancing this there's the slight interest of another Sturges self-portrait: a humorous writer who doesn't consider himself funny in real life.

If the movie was truly terrible, and if the faults were attributable clearly to mistakes willfully committed by its writer-director, then we could use it as a gravestone for Sturges's talent and say that he wore himself out battling the Hollywood machine, or burned too brightly, or killed his creativity with self-indulgence. The truth behind this weak, moderate, anonymous effort is actually much sadder: it's entirely possible that Sturges was still a genius at the end of his life, capable of giving us films as uproarious and generous as Sullivan's Travels and The Palm Beach Story and The Miracle of Morgan's Creek, but no one would let him.

"These ruminations, and the beer and coleslaw that I washed down while dictating them, are giving me a bad case of indigestion. Over the years, though, I have suffered so many attacks of indigestion that I am well versed in the remedy: ingest a little Maalox, lie down, stretch out, and hope to God I don't croak." —Preston Sturges, Sturges on Sturges.

***

The Forgotten is a regular Thursday column by David Cairns, author of Shadowplay.