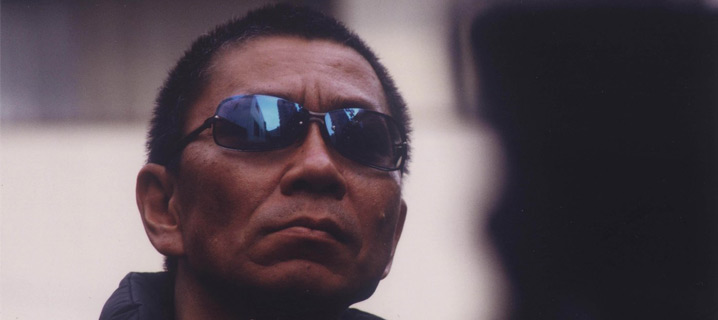

Takashi Miike's body of work encompasses the most diverse approaches to filmmaking of any director alive today, from direct-to-video police dramas to avant-garde art movies. On top of this, Miike seems to make no distinction between modes of filmmaking—not only from project to project but within each film itself. His closest American equivalent might be Quentin Tarantino, who shares a wildly egalitarian view of film history, but Miike is almost unique among living filmmakers in that he advances this view within a traditional studio system. Where Tarantino, who makes a film every few years, is expected to produce Art, Miike, who releases anywhere from two to seven in a given year, can operate below such scrutiny. Forgoing Art, Miike has built a career at the intersection of work and play.

And yet Miike's experience in the art world (working with one of Hou Hsiao-hsien's producers on Izo, for instance, or staging a traditional ghost story for the Tokyo stage) remains evident even in familiar genre assignments. Sometimes it appears in the form of surrealist non-sequiturs, like the garish outfits worn by an otherwise gentle old man in White Collar Worker Kintaro; elsewhere, an avant-garde sensibility overwhelms the work completely, as in the lengthy static shots that crop up even in the Dead or Alive trilogy, hitmen-themed action films. Where this sensibility at times recalls Luis Buñuel's work in the Mexican studio system, there's little in Miike's films that could be labeled subversive: Rarely does an out-of-place genre reference or behavioral choice imply social critique. But if Miike's surrealism is inadvertent (and many of his interviews, in which he claims to be working largely by intuition, would suggest this), it is no less worthy of critical consideration, given how surprising, confounding, and generally joyous is the filmmaking surrounding it. If anything, his connection to such a wide variety of images makes him better qualified to reflect the tangled cultural subconscious at the dawn of the 21st century.

When Miike's films are discussed (at least in English), it's typically in terms of overall output or the overriding "craziness." This makes sense, given his rate of productivity, but it's unsatisfying if one wants to understand how the films operate and how they act on an audience. (A noteworthy exception to this trend: Tom Mes' instructive book Agitator: The Cinema of Takashi Miike.) The dearth of serious writing is especially surprising when no director this decade came closer to making movies the way cinephiles have learned to assimilate them. It's not uncommon for today's moviegoer to watch a Jerry Bruckheimer production and a minimalist work by Pedro Costa in one evening, in spite of the bill presenting some irreconcilable contradictions. The Bruckheimer takes for granted not only genre cliches but the obligation to recycle them over and over, past the point of plausibility, in the name of ceaseless spectacle. A film by Costa (or, to cite one of Miike's peers, Pen-ek Ratanaruang) tries to deny spectacle entirely, opting instead for careful, unobtrusive observation. Both approaches seem symptomatic of the Information Age (submission to a wave of facts, vigilant surveillance), but they may as well exist in different media, seeing how little the actual films resemble each other.

Incorporating sources as diverse as these—as well as many, many others—Miike's films suggest a common ground where all moviemaking can converse. Not since Jean-Luc Godard in the 1960s has a filmmaker's approach to cinema been this holistic. But when Godard started making films, the distance between Antonioni and Monogram Pictures (to cite two poles of art and commerce) was not nearly as large as the gulf that today separates Bruckheimer and Costa. To bridge these two in a single film is to risk madness, but such wild combinations also carry the promise of new discoveries, perhaps a new cinema that makes old distinctions irrelevant.

This introduction will begin a series of essays that will look at selected films Takashi Miike has directed since the year 2000. It will look at the films themselves (in terms of theme, character, tone, etc.) and how each one reacts to various currents of filmmaking. It's an exercise that doubles as a survey of cinema today; we hope it yields something like a unified image. Because no matter what was going on in movies these past ten years—low-budget experiments on digital video, CGI-filled fantasies, direct-to-video knockoffs of bigger hits, the global minimalist movement, musicals for pre-teens, the arthouse appropriation of hardcore sex, the rebirth of exploitation film gore—Miike was there, attempting something like a democratic overhaul of it all.

***

INDEX

(1) Two Movies at Once: "Dead or Alive 2: Birds" (2000)

(2) The Cinema of Gratitude: "Deadly Outlaw Rekka" (2002)

(3) The Blue Hour: "The Guys from Paradise" (2000)

(4) The Drift: "Graveyard of Honor" (2002)

(5) Unwatchable, Essential: "Izo" (2004)

(6) A Superhero is a Superhero: "Zebraman" (2004)

(7) A Nap of Kings: "Big Bang Love, Juvenile A" (a.k.a. "4.6 Billion Years of Love") (2006)