Pigeon-holes are terribly useful things, it seems. Film-makers who can't be shoehorned into one or the other have a way of falling down the cracks. Now, that is a pretty awesomely mixed bunch of metaphors, but let's go with it for now.

Jean Epstein is the phenomenon under analysis, and the problem for the pigeon-holers is immediate and insurmountable. An important strand of his work relates to German Expressionism, another to surrealism (or the kind of surreal-affiliated yet non-surrealist work exemplified by Jean Cocteau or Marcel L'Herbier: what we might call surrealish), and another is pure proto-neo-realism, interweaving drama and documentary. Abel Gance was an influence, stylistically and in terms of his novelistic ambition and realism. Luis Buñuel was a collaborator. Epstein was a theorist as well as a practitioner. He embraced aspects of melodrama, experimented with different styles, adapted Poe (The Fall of the House of Usher, 1928) and Balzac (L'auberge rouge, 1923) and didn't quite settle into a pattern, although many of his later movies are "island films" (note how I drop that term in as if it were some kind of recognized thing).

So here are two Epsteins, contrasting in most ways, offering a peek at the mind behind the images, which may be impossible to fully apprehend even after a complete retrospective, which may never happen...

Mauprat (1926), adapted from a novel by George Sand, is a revelation due muchly to the presence of Nino Constantini. Some actors have bone structure. Some actors, like Constantini, are bone structure. But Constantini is more than a striking physiognomy: the actor he most resembles is Buster Keaton, partly in face and partly in manner: his way of walking, directly and seriously, straight towards the thing of fixating interest in the scene, calls to mind the Great Stone Face. Epstein's way of filming him shows what would have happened if Keaton had given himself giant wide-angle-lens closeups: we'd have been unable to laugh, too hypnotized and awe-struck and afraid.

Constantini is young Mauprat, a nobleman raised by a debauched bandit of an uncle, rescued by the respectable side of the family and hopelessly in love with his strong-willed cousin. He's like a feral creature fitted with a powdered wig. Like Epstein (a Russian/Polish immigrant in France), he doesn't fit alongside the other pigeons.

Meanwhile, there's a good 19th century plot, culminating in a murder attempt and a trial, with surprise revelations and disguises and unmaskings, but none of that matters very much, because Epstein's mind and eye are sharply focused on his star and on the landscape. The trees get a lot of shots all to themselves, not as backdrop but as supporting cast, animated by Epstein's moving camera. He glides down avenues of swaying trees, like an arboreal stargate, or cuts to them billowing in the breeze to evoke the characters' emotional turmoil. Rocky outcrops and drifting clouds are also enlisted into the moodscape.

And at the climax, still addicted to poetry and dreamstuff, Epstein disposes of a villain by having him simply fade out, a laughing phantom, a completely aberrant element in an otherwise quasi-naturalistic drama.

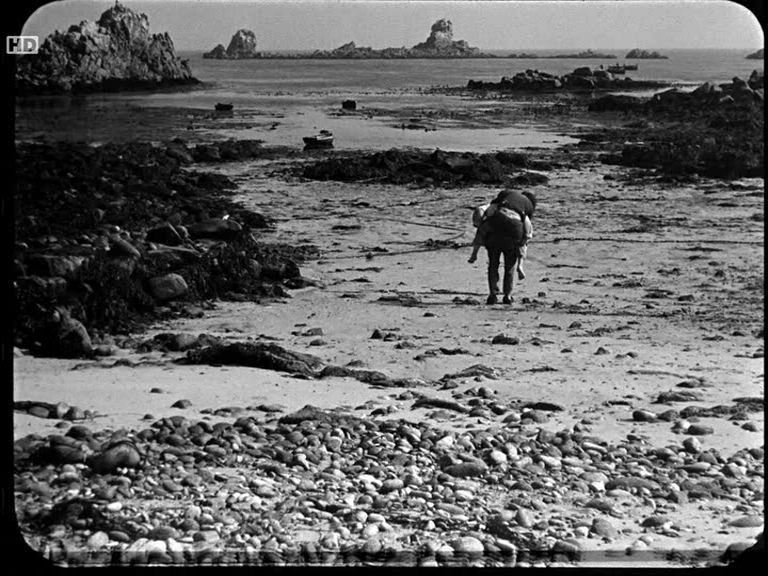

Finis Terrae (1929), appears in many ways as a complete contrast to Mauprat. It deals with a group of four men gathered on an unpopulated, rocky island to gather kelp. One becomes sick with blood poisoning and a rescue attempt must be mounted. The slender narrative (that is really all there is to it) allows Epstein to drift, somnambular, fixing on waves that crash in great powdery nebulae on the primordial rocks. With its bug-eyed wide-angle lenses, bobbing handheld camera, slow-motion and macro-closeups of shingle and broken glass, feels defiantly modern compared to the fog-filtered mustiness that lends Mauprat much of its antique atmosphere. The movie also contrasts strikingly with Michael Powell's island film of (almost) the same title, Edge of the World. The approach to landscape is different, with Powell eschewing any flavor of documentary, dramatizing his landscape and yoking it to narrative ends, while Epstein's world of stone and salt water rises up and swallows his story in one gulp.

The intensity and sharpness of the images has a feverish grip, so that when the sick boy starts to hallucinate, the movie almost oversteps its stylistic bounds by trying to evoke a state the audience is already in: Epstein snap-cuts a jangling montage of looming ECUs and what look like off-cuts and deleted scenes into an abstract nightmare that threatens to turn the whole experience into abstraction and dissonance, with no way out save the declaration of a cinematic Year Zero from which we can start afresh. Seriously, the movie feels like it was made tomorrow, or at any rate made in 1929 by time-travelers.

***

The Forgotten is a regular Thursday column by David Cairns, author of Shadowplay.