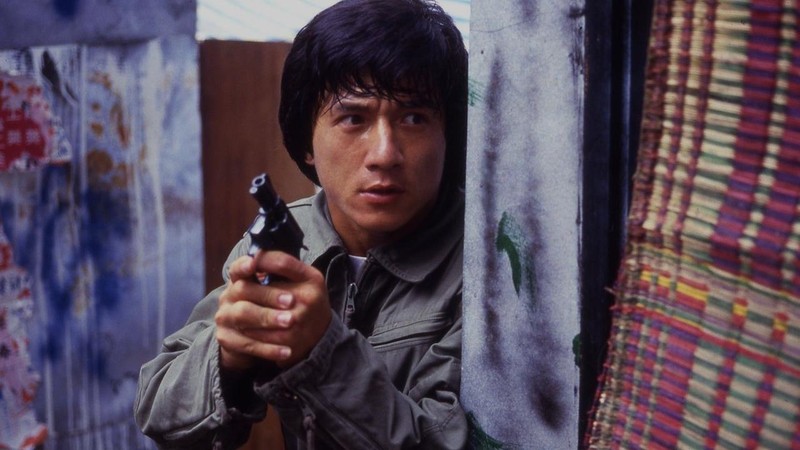

After a second failed attempt to break into the American market with The Protector (1985), a film in which he repeatedly conflicted with director James Glickenhaus, Jackie Chan returned to Hong Kong determined to top Hollywood. According to Chan, he told Glickenhaus: “You do The Protector and I’ll do Police Story, and I’ll show you what the action movie is all about.” Today, more than 30 years after its release, Police Story remains one of the best-loved and most impressive action films by the most popular action star in the world, and has been given the restoration treatment and Metrograph engagement befitting a true classic, while Glickenhaus is best known for actually writing and directing a movie called McBain.

After knocking around Hong Kong for several years as a stuntman and bit player, and a few attempts at becoming a lead in cheap Bruce Lee knock-offs, Jackie Chan finally burst into superstardom with a pair of films he made in 1978, Snake in the Eagle’s Shadow and Drunken Master, irreverent and vulgar action-comedies directed by Yuen Woo-ping and starring Simon Yuen Siu-tien, Woo-ping’s father. The films soundly parody the somber master-student dynamics of classier Shaw Brothers productions like those of Chang Cheh and Lau Kar-leung, blending a heady dose of scatological humor and low-brow Cantonese jokiness with their breathtaking and ingenious fight sequences, Yuen’s creativity as a choreographer perfectly matched with Chan’s unusual set of skills.

Sublimely acrobatic, strong and fast, Chan was, the story goes, always a mediocre student at the China Drama Academy, where he’d been left by his parents at the age of seven and studied for a decade, starring as one of the troupe’s Seven Little Fortunes.1 His fighting lacks the long-limbed grace of fellow students Yuen Biao and Yuen Wah, or the unexpectedness of Sammo Hung’s portly agility. But what he does have is an indestructible body and a supernatural willingness to absorb punishment. In the early films he takes beatings far more brutal than anything Gordon Liu or Alexander Fu Sheng would have endured, and as his career progressed Chan would make putting his life in danger the very center of his filmmaking approach, building his films not around story, character or ideas, but stunts: the more deadly the better. The end credits of his films, early on replays of his most impressive feats, would quickly become a compendium of stunts gone wrong, audiences lapping up footage of Chan and his stunt team very nearly killing themselves, repeatedly, for the sake of making cinema.

Immediately following his 1978 hits, Chan began directing his own films, starting with Fearless Hyena (1979) and The Young Master (1980), and then his first attempt at cracking Hollywood, Battle Creek Brawl (directed by Enter the Dragon’s Robert Clouse). He returned to Hong Kong and directed Dragon Lord (1982) and his first collaboration with Sammo Hung and Yuen Biao, Project A (1983). That same year he and Yuen also played bit parts in Hung’s ensemble action comedy Winners & Sinners and in 1984 the three teamed up for their masterpiece, the Barcelona-set Wheels on Meals. This was followed by The Protector and then Police Story. Unlike Sammo Hung’s films, almost always ensemble works where the director-star recedes into the background for large sections of the film, providing ample showcases for his peers, Police Story is a one-man show. Chan is the only action star of note, rather than overcome a comparable opponent (like he does against legendary fighter Benny “The Jet” Urquidez in both Wheels on Meals and Sammo’s 1988 Dragons Forever), Chan’s foes are faceless masses of stunt men. And rather than defeating them by some new kind of self-knowledge or mastery of technique (as in Lau Kar-leung’s kung fu films), Chan fights with desperation and wins through improvisation, manipulating the found objects of his environment in ingenious and wholly unexpected ways. The film is bookended by audacious stunts, the first a wild car chase down a steep hill through the homes and makeshift buildings of a squatter’s village followed by Chan on foot chasing down and hanging off of a speeding bus. The finale is ten minutes of glorious mayhem, as Chan tracks the villains to a shopping mall and proceeds to shatter every glass surface in the building before making a still mind-boggling leap onto a metal poll and sliding down three stories through myriad electric lights. The lights for this stunt were actually not connected to a low-power battery like they should have been, giving Chan much more juice than he expected and causing second-degree burns on his hands, but the most remarkable thing about the stunt is that after sliding down and crashing through glass and some kind of display-house roof, Chan hops right up and continues the chase, all in one unbroken take.

In Police Story, Chan plays a cop named Chan Ka-kui (as in many of his films, this was translated to “Jackie” for overseas release, and in some versions he’s also inexplicably called “Kevin”). He’s assigned to watch over a hostile witness in a drug trafficking case, played by Brigitte Lin2. The middle section of the film mostly follows Chan’s attempts to first keep Lin in line and second gather new evidence against the head gangster (played by the great Shaw Brothers director Chor Yuen) after Lin escapes. All this while trying to keep his girlfriend, played by Maggie Cheung in one of her earliest screen appearances, from leaving him due to his antics. There are a few fight sequences in this part of the film, in what is a standard Chan setup: he’s alone or protecting a woman while beset by an army of bad guys in an unusual location, the different parts of which Chan will utilize to even the odds against the enemy. In this case, the fight is in a parking lot, with Chan weaving in, around, and through various quickly demolished cars. In later films it’ll be a playground in a park, or a warehouse, or an underground bunker, but the effect is always the same: we marvel at Chan’s speed and fluidity, while every new use of a car door, or refrigerator, or shopping cart takes our breath away.

Just as good as the fights though are Police Story’s comic set pieces, especially one totally unrelated to any kind of plot development, which finds Chan alone in the precinct office as everyone else goes to lunch. He’s left to answer the phones, all the phones, as they ring one after another, Chan sliding around in his desk chair, juggling cords and receivers with manic grace as he fumbles every call. This is the kind of classic comedy-inspired bit Chan excelled at, even more so than his undoubtedly impressive recreations of Harold Lloyd and Buster Keaton stunts in the Project A films. Unfortunately, they would become all too rare in his later movies, traded-in for pithy moralizing and goofy pre-digital gadgetry.

Police Story then is Jackie Chan at his peak, his greatest work as a director. In his next films, the Armor of God series, sequels to Project A and Police Story, Chan takes even more of the focus, without even non-fighting stars of comparable wattage to balance him out. At the same time, the fights become more infrequent, replaced by ever more complicated vehicle stunts, and the humor more stilted (the low point being Chan’s unwatchable buddy hijinks with Alan Tam in Armour of God). In fact, Police Story is the only one of Chan’s directorial efforts that stands with the best of his work with other directors: the Yuen Woo-ping films, Sammo Hung's Wheels on Meals and Mr. Nice Guy, Lau Kar-leung’s Drunken Master II, Ringo Lam and Tsui Hark’s Twin Dragons, and Kirk Wong’s Crime Story.3

The latter is an interesting point of comparison, in that it was conceived as a kind of grittier variation on Police Story itself.4 Police Story ends, after all the broken glass, with a berserk Chan unable to be held back by his fellow officers as he pummels the surrendering villains, now in police custody. It’s a story of a happy-go-lucky cop driven mad by the unrelenting violence and dishonesty of the criminal element, to the point that the law itself can no longer contain him. As such, it’s a kind of outgrowth of the vigilante crime movies America was making in the 1970s (The French Connection, Dirty Harry, Death Wish, et cetera) which were themselves influential on the Hong Kong New Wave which flourished at the end of that decade and into the next. Police Story was Chan’s first modern day film, but it came near the crest of the wave that began in response to scandals in the Hong Kong police force and a generation suffering under extreme disparities in wealth produced by the refugee influx into the colony at the end of the 1940s5 and the economic boom of its laissez-faire approach to capitalism. Films from Josephine Siao and Po Chih-leong’s Jumping Ash (1976) to Tsui Hark’s Dangerous Encounters-First Kind (1980) and Johnny Mak’s Long Arm of the Law (1984) explored the seedy interconnections between cops and criminals in an overcrowded and chaotic Hong Kong, and Police Story, with its twin poles of shantytown and luxurious shopping plaza is solidly in this tradition. But it's a place Chan would hardly ever venture again in his own directorial work. Far from interested in sophisticated political critique, Chan choose instead to cast himself as the sunny optimist, and proceeded to go wherever the money would take him. Anticipated within the film itself, Chan’s image and the theme song he sang for Police Story would become ubiquitous in advertising for the actual Hong Kong police itself, despite the film’s pointed critiques of cowardice, bureaucratic inefficiency, corruption, and basic incompetence in the force. Eventually, Jackie Chan even made it in Hollywood, making big bucks in movies for Brett Ratner, and for the last decade plus he’s been splitting time between there and Mainland China, putting out the occasional decent film (like Ding Sheng’s Railroad Tigers) but mostly starring in embarrassments like Dragon Blade and Kung Fu Yoga.

1. The group had a rotating cast, so there were more than seven in total, many of whom adopted the name of their teacher as a surname. Former Fortunes who made it big in the film industry include: Chan, Sammo Hung, Yuen Biao, Corey Yuen, Yuen Wah (the villain in Police Story 3: Supercop), Yuen Bun (best-known as Johnnie To’s regular action director) and Yuen Qiu (who was the landlady in Kung Fu Hustle).

2. Lin was already a major star at this point, one of the “Two Lins and Two Chins” who starred together in several Taiwanese hits in the 1970s. Interestingly enough, the other Lin, Joan, has been married to Jackie Chan since 1982.

3. Chan did make a couple of fine films with Stanley Tong, a former stuntman who more or less served to direct Chan’s ideas in Police Story 3: Supercop and Rumble in the Bronx and several lesser films.

4. Also of note as a response to Police Story is Corey Yuen and Yuen Biao’s 1986 Righting Wrongs (a.k.a. Above the Law), in which Biao plays a prosecutor who starts killing the crooks he can’t convict, only to uncover even greater corruption within the police force itself. It's much bolder in exploring the themes of corruption and vigilantism than Chan’s film, while also providing for Biao and Cynthia Rothrock some of the craziest stunts and fights ever put on screen.

5. Including Chan himself. His parents’ experience in World War II is chronicled in the lovely wartime romance A Tale of Three Cities, directed by Mabel Cheung who, with her partner Alex Law has made at least three films out of Chan’s personal history. Their 1988 film, Painted Faces, is about the Seven Little Fortunes’ time at the Peking Drama Academy, with Sammo Hung playing their teacher.