Gremlins (1984)

Gremlins (1984)

Towards the end of his latest book, Make My Day: Movie Culture in the Age of Reagan, film critic J. Hoberman highlights Charles Musser’s Politicking and Emergent Media: US Presidential Elections of the 1890s, a historical study that demonstrated how “the candidate most adroit in deploying new communications technology almost always prevailed.” Extrapolating from this, Hoberman points out Roosevelt’s “successful use of radio,” Eisenhower’s “pioneering TV commercials,” and Kennedy’s victory over Nixon which was secured over televised debate—after which he moves on to Ronald Reagan, the book’s prime player. The final entry in the author’s “Found Illusions” trilogy, Make My Day completes the long-gestating historical project Hoberman started in 2003 with The Dream Life and extended with 2011’s An Army of Phantoms. Thus, it's both a culmination of the author’s considered, career-long engagement with American film culture, and a kind of corollary to Musser’s study, demonstrating how Reagan triumphed over Jimmy Carter and Walter Mondale to inaugurate an “entrancing period of American self-absorption and patriotic solipsism”: the Age of Reagan.

By the author’s own admission, Make My Day is neither a work film criticism nor a strict historical account, but “a chronicle in which political events and Hollywood movies are folded into each other to illuminate what, writing in 1960, Mailer termed America’s ‘dream life.’” As such, the book’s discussion of, say, Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver (1976) differs significantly from Robin Wood’s explication of the movie as an “incoherent text,” a designation that’s here applied to 1982’s Poltergeist. (“On the one hand, the movie concerns a childhood fear of separation and an adult fear of loss… On the other hand, Poltergeist appears to have something to do with American history—or rather, a-history.”) Hoberman’s stated interest in the films under discussion are primarily as contemporaneous documents, so passages frequently ping-pong between production details, critical narratives, and political developments in the U.S. and beyond.

Unlike Andrew Britton’s 1986 essay “Blissing Out: The Politics of Reaganite Entertainment,” which Hoberman references in a passage on 1984’s Gremlins, Make My Day was not written “in the heat of the moment.” Accordingly, it’s able to function as a kind of historiographic survey, with contemporaneous reviews from writers such as Pauline Kael (“the Cold War’s preeminent sociological film critic”), Andrew Sarris (whom Hoberman worked alongside at the Village Voice), and the New York Times’s Vincent Canby cited and contextualized throughout. A professional critic during the Reagan years, Hoberman also reprints a number of his own articles, such as an extended Oedipal reading of Tony Scott’s Top Gun (1986) titled “Phallus in Wonderland,” an amusing piece that he notes was received somewhat contentiously at the time. In its way, then, Make My Day—started during Obama’s second term, and completed after Trump’s election—serves as a documentation of its writing. Present, if implicit throughout the book—the product of a coherent political, ideological, and aesthetic position—is an awareness of the seismic shifts in film journalism and criticism that have occurred since Hoberman first started as a critic. Or, in other words, the inexorable move towards fractured, self-negating cycles of Internet-era discourse which are distinctly inhospitable to the very writing that he put forth at the now-shuttered Village Voice.

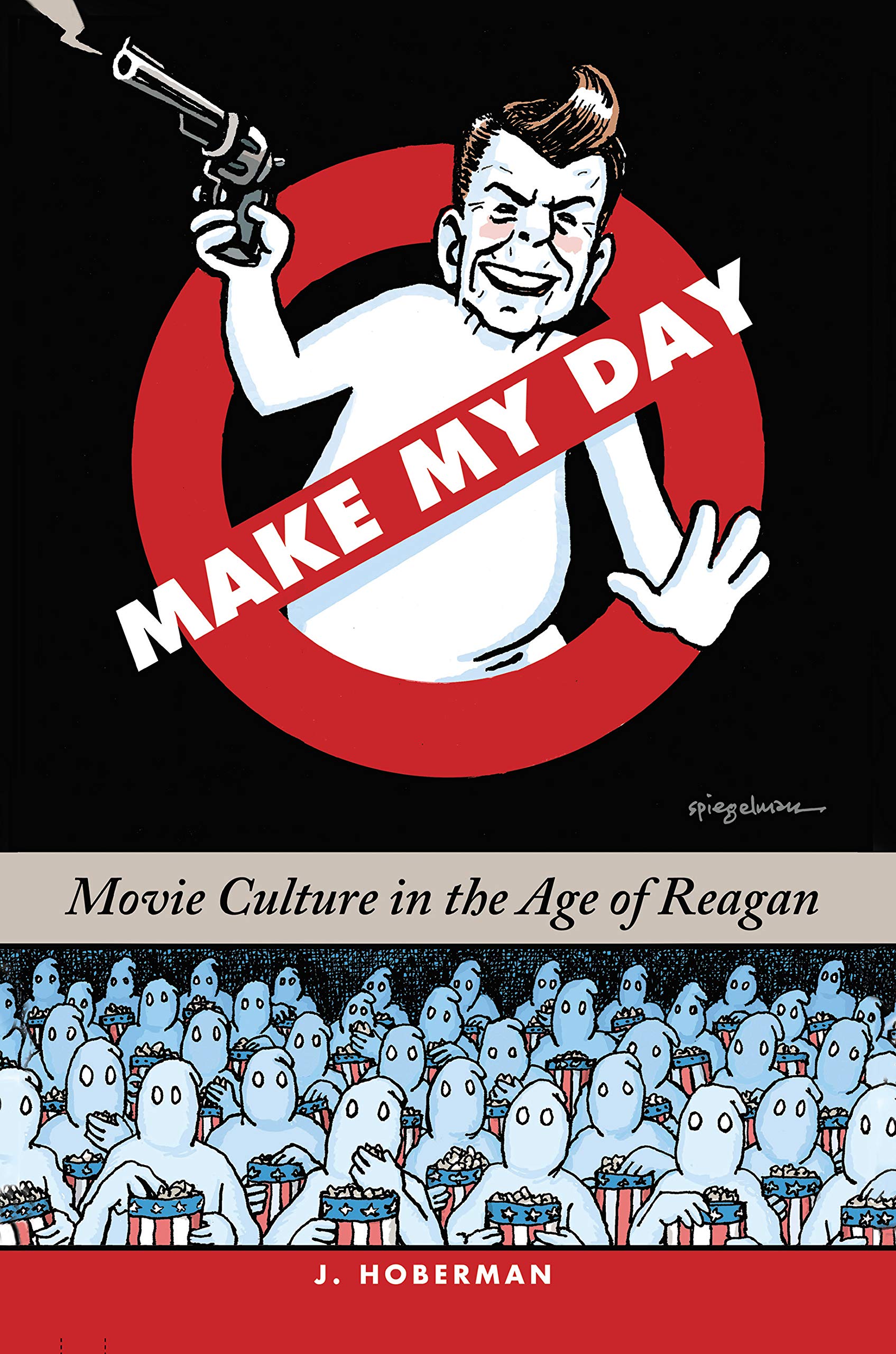

In discussing the unprecedented success of 1984’s Ghostbusters (an “aesthetically weak, but ideologically potent” film that’s central to the book’s thesis, and which provides the inspiration for its cover art), Hoberman quotes from Todd Gitlin, who describes the way “the sum total of the publicity takes up more cultural space than the movie itself.” Without qualification or modification, the statement ably captures the current media topography—not to mention the marketing for and reception of the 2016 gender-swapped iteration of the Ivan Reitman-directed original. As Hoberman puts things in a recent interview with Filmmaker magazine: “There’s no platform for cultural reporting tied to a specific place, in my case New York City and a particular editorial mission. The internet is what we have now, and if anything, the audience is even more divided.” But let’s not get too nostalgic.

Before Reagan could take center stage, the necessary conditions had to be met—and Make My Day’s first hundred or so pages are dedicated to laying those out. With reference to Frederic Jameson, Hoberman puts forth George Lucas’s American Graffiti (1973)—a “total immersion in an imagined past”—as emblematic of the era’s gradual tilt to nostalgia for the 1950s. For him, the film’s underlying ethos, along with the disillusionment of the Carter years, paved the way for the “process of illusionment” through which Reagan “reversed the flow of time and remade our days.”

The title of Hoberman’s book comes from the Clint Eastwood vehicle Sudden Impact (1983), but this line of thought is the crux of its narrative. (It is perhaps the early chapter “Nashville Contra Jaws, 1975,” however, that most handily encapsulates Hoberman’s talents as a cultural writer-observer, itself working as a handy encapsulation of the myriad oppositional forces—political, cultural, and otherwise—at play during that time.) Once Reagan is elected, the narrative’s contours sharpen, and the rest of the book’s 300 or so pages unfold chronologically, in two-year segments, through the president’s two terms.

In the preface of Make My Day, Hoberman describes the book as “a good deal more personal than its predecessors,” and if it feels so for even those readers born after Reagan’s presidency, that’s in part because the era clearly anticipates the contemporary media landscape. Indeed, a striking aspect of reading Hoberman’s account is realizing the extent to which the nascent personalities and intellectual properties of the late ’70s and ’80s have not just persisted, but also remained frighteningly dominant. Spielberg and Lucas continue to cast a long, inescapable shadow over most of today’s Hollywood blockbusters, while the Star Wars sequels require no introduction. There’s also the matter of the Rocky sequels, and even a fast-approaching Top Gun entry. And then of course there’s Disney—an entity that’s connected to Reagan not just through the opening of Disneyland, which he hosted, but also in the entire “sense of the U.S. as kitsch theme park,” which became inescapable during his second term: “By 1986, an avant-pop version of American self-absorption had become common currency,” Hoberman writes, leading into a discussion of the few notable media of that summer to traffick in a sense of disquiet: Jonathan Demme’s Something Wild, Alan Moore’s Watchmen, and David Lynch’s Blue Velvet.

Throughout the book, Hoberman highlights Reagan’s viewing habits (as recorded in personal diary entries and screening logs at the White House and Camp David), both to illuminate its relationship to his presidency (from the Star Wars initiative to lines of his speeches), and to draw out the way the movies gradually became shaped by the media age that he so adroitly navigated. Of the resulting ouroboros of spectatorship, there’s no clearer instance than Reagan’s double-bill of 1943’s This Is the Army (“a star-studded showcase for… the young Ronald Reagan”) and Robert Zemeckis’s Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988), a film whose “true premise” was that “in the age of all media, we live our lives in a thicket of cartoons and trademarks.”

That last observation benefits, of course, from being written from within a 21st century landscape that increasingly resembles the 2045 garbage heap of Spielberg’s Ready Player One (2018). And that aspect of this writing is one that Hoberman certainly turns to his advantage. That said, references to various theorists from Adorno to McLuhan also point up to one of the self-inscribed limitations of Hoberman’s project, which is that it treats the movies under discussion primarily as rich political allegories and revealing texts. There is, of course, ample aesthetic engagement, and the micro-histories of specific films, as refracted through various critical lenses, are a source of fascination throughout. But in general, a macro-view discussion of stylistic shifts and nascent (or declining) filmmaking paradigms—particularly those occurring outside the purview of the mainstream media—remains beyond the book’s scope, and is secondary to the dominant political narrative.

Blue Velvet (1986)

Blue Velvet (1986)

More germane, perhaps, is the fact that when taken in long view, Make My Day also leaves a fair amount of room for more productive generalization. For the segment on Blue Velvet and the fantasies of “Reaganland,” Hoberman draws from the French philosopher Jean Baudrillard to discuss manifestations of “the new imperial, triumphantly fake AmericanArama… rooted in the Happy Daze of the 1950s.” But in general, such forays into more explicitly theory-heavy pronouncements are less sustained than one would prefer. Alongside the book’s overall thesis, one might for instance point to a 1992 column by Cahiers du cinéma critic Serge Daney: Published in Libération under the (translated) title “The market of individuals and the disappearance of experience,” it is nominally about the success of reality TV, but is for its relevance, here worth quoting at length:

With this market of the individual, of which the American reality-TV shows are but the latest symptom, we can spot what must be lost and the price that must be paid. The idea of human experience is definitely lost. It’s as if television had suddenly sat down a whole people on the couch of a psychoanalyst who would work on an assembly line and who would, instead of listening silently to the too beautiful rants of the legendary Self, applaud the patient at the first session and tell him: you are sublime, everything you have said is exactly what you have lived, re-enact it in our home-TV-style (which is your home by the way) and you will be cured.

The above passage was written after Reagan’s presidency, but read even today, its prescience seems difficult to overstate—and also plugs directly into the implications Make My Day’s overall narrative. To put Hoberman’s argument in Daney’s terms: If the 1980s indeed saw the rising market of the individual, then Reagan’s political dominance was directly related to his navigation of its image-based peculiarities. (“Post-Reagan, the presidential debates were understood to be meta-debates,” Hoberman observes later on.) And the market hasn’t gone away—far from it. Just as Reagan emerged as a kind of specter in The Dream Life and Army of Phantoms, so Trump appears here as a villain-in-waiting, versed in the principles of reality TV, and able to “[assimilate] the logic of the blockbuster,” understanding that “publicity was more important than content.” Implicit links to Trump are scattered throughout the book, but Hoberman confines his most forceful observations to the 13-page epilogue, in which he describes the sitting president as “a beneficiary of Reagan-nostalgia, which is to say, a nostalgia that is nostalgic for nostalgia itself.”

The parallels between Reagan and Trump are ultimately ancillary to the main thrust of Make My Day—and anyway, such a study might be too gargantuan a task for any one writer. Nevertheless, there’s a sense in which the book dives into the past in order to somehow make sense of a maddening, irrational present. As this account of Reagan’s ’80s unfolds with Hoberman’s recognizable verve and erudition, there’s an anticipatory sense that it might somehow point the way forward—if only in terms of our present engagement with various media. Needless to say, Make My Day doesn’t do anything quite so grand. If anything, it refuses the definitive—which is entirely in keeping with Hoberman’s excoriation of those films such as Ghostbusters that diagnose ills and cynically proffer themselves as the cure.

What it does offer the contemporary reader is both an uncanny familiarity and a commensurate sense of disquiet—for, as Hoberman asserts at the close of his account, “the Reagan movie did not end in January 1989, at least in the Dream Life.” Indeed, reading Make My Day, one might easily find oneself drifting once more to none other than Lynch—whose Twin Peaks: The Return (2017) could be said to do for this era what Blue Velvet did for the 1980s—and asking: What year is this?