“…[O]ne must ultimately admit that, more than anything else, Surrealism attempted to provoke, from the intellectual and moral point of view, an attack of conscience, of the most serious and general kind…”

—Andre Breton, “Second Manifesto of Surrealism,” 1930

“Camp,” “psychedelic,” “surreal;” all these terms invariably come into play in Busby Berkeley’s 1943 musical The Gang’s All Here. The camp aspect is mostly incarnated in the larger-than-life form of Brazilian-born entertainer Carmen Miranda, and the iconic image of her head sprouting a bumper crop of bananas; although the political sensitivities of the day inhibit the untrammeled delight that camp connoisseurs took in Miranda in the ‘60s, when Gang was often revived as a somewhat gayer iteration of “the ultimate trip.” “Psychedelic” came in through that door as well, naturally; this was the first Berkeley musical to present his elaborate, unstuck-in-space musical production numbers in glorious Technicolor. “Surreal”? Well, going by the Breton quote above, not to mention any number of pronouncements he and other representatives of the putatively genuine article, not so much. Or maybe just small-s surreal. Berkeley’s visions are, among other things, uniquely American, having more to do with the fantastic gigantism of Winsor McCay, expressed to the most eye-popping effect in popular comics series “Dreams of the Rarebit Fiend” and “Little Nemo in Slumberland,” than the lonely, sometimes erotically charged landscapes of di Chirico and Ernst. Of course, both of McCay’s series were about life in dreamworld, and the capital-S Surrealists spent much of their creative time there themselves.

As someone whose delight in Gang is practically inexhaustible, I took the release of a newly remastered DVD version of the film (released June 17 as part of Fox Home Entertainment’s “Carmen Miranda Collection”) as an opportunity to look for moments within that might pass muster with a genuine Surrealist. In another essay, “As In A Wood,” reproduced in Paul Hammond’s invaluable collection The Shadow and Its Shadow: Surrealist Writings on the Cinema, Breton recalls of his flaneur-esque forays into the cinemas of Paris, “…[W]hat we valued most in [the cinema], to the point of taking no interest in anything else, was its power to disorient.” On the commentary track of the DVD of Gang, film scholar Drew Caspar rhapsodizes about the film’s opening shot—a face, illuminated in a field of black, floating in that field and singing—as if it is the ultimate in such disorientation. Well, yes and no. The audience is already aware that Gang is a musical, and that its director is well known for the unusual effects he brings to his musical numbers; if it takes several minutes to fully understand that everything subsequently unfolding on the screen is “really” taking place as the floor show of a New York nightclub, well, it’s not that much of a big deal; the audience can float on this cloud quite contentedly. And so it goes, more or less, throughout.

And yet…

Gang has a storyline, not that you’d ever know it from most accounts of the film, as it’s the least of its features. In brief: soldier and soon-to-be-WWII-hero Andy Mason (James Ellison) romances showgirl Edie Allen (Alice Faye) in spite of the fact that he’s ostensibly engaged to Vivian Potter (Sheila Ryan), his childhood sweetheart. Mason and Potter’s fathers, played by corpulent Eugene Pallette and sniffy Edward Everett Horton respectively, are Wall Street fat cats who have the grand idea to import the entirety of Edie’s troupe to Westchester to put on a war-bond raising entertainment. There, Mason Jr.’s ruse is exposed. Of course the whole thing is smoothed over, rather hilariously, in the middle of the climactic musical number, with Vivian shrugging to Edie, “We never really loved each other.”

Prior to all this, though, we see young Mason acting rather a shit, camouflaging his actual identity in order to cozy up to Edie at a USO canteen, pretending to be poor when he’s a scion of privilege, etcetera. Putatively street-smart Edie swallows this lock, stock, and barrel, particularly after he goads her into singing her future feature number, “A Journey to a Star” on the Staten Island Ferry. After he sees her to her door, there are three shots that, for some reason, produce a genuinely Surrealist frisson, as Edie looks to the sky…the starlit sky does not look back...and Edie, um, continues to look at the sky. The shots serve no real narrative function, unless you consider the opportunity to reprise “Star”’s melody to be a narrative function. But the vulnerability Faye projects is almost, well, conscience-provoking.

(Incidentally, Faye had an avid admirer in the one-time Surrealist and Oulipo founder Raymond Queneau, who gave the heroine of his beloved novel Pierrot Mon Ami the physical characteristics of Faye; he went even further in the novel Saint Glinglin, naming its heroine “Alice Phaye.”)

These shots constitute a potential pre-echo of the capital-S Surrealism of the denouement of Robert Siodmak’s 1946 Christmas Holiday, in which Deanna Durbin communes with the night sky to the strains of the “Liebestod” from Wagner’s Tristan and Isolde, which scored a, um, somewhat similar sequence in Bunuel and Dali’s Un Chien Andalou.

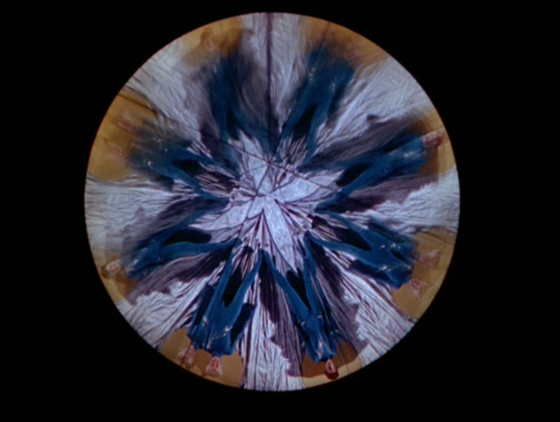

Another instance of genuine disorientation in Gang is perhaps not so deliberate. (That’s assuming the aforementioned instance was deliberate, I know.) A penultimate musical number, the pretty much out-of-nowhere “Polka Dot Polka” (one imagines songwriter Leo Robin and Harry Warren on laughing gas as they conceived it), replete with what look to be purple neon hula hoops, starts giving way to near-complete abstraction as Faye, sheathed from the neck down in what appears to be a football-field sized gown, starts a back-and-forth circular motion that leads into a literally kaleidoscopic interlude, in which all recognizable human forms seem to disappear.

Soon enough another tune begins to swell, and we are treated to the sight of the disembodied head of Eugene Pallette on a blue tablet, thrusting his face forward and bugging out his eyes as he gives gravel voice to the final chorus of “A Journey To A Star.” His disembodied head is soon joined by those of the rest of the film’s characters, all of whom are now star children or something, one might guess. But the sight of Pallette is pretty hard to shake.

Andre Breton might not have approved. But he would certainly have been…disoriented.

***

While researching this article, I contacted the legendary jazz drummer Louie Bellson, featured in Gang playing in Benny Goodman’s band. I wanted to solicit some memories of the film, and he was happy to oblige; his interlocutor and transcriber for the occasion was his wife and manager, Francine Bellson. Here’s Louie:

“I was working in Hollywood playing in Ted Fio Rito’s band. One day, Benny Goodman’s brother Freddy asked me if I’d like to join the Goodman Band. When I answered ‘Yes,’ he said, ‘Meet me on the 20th Century Fox set tomorrow morning.’

There were no rehearsals or anything. They just put a tuxedo on me and ‘bam’! The next thing I knew, I was playing onstage of a huge Hollywood set. It was magical. I was only a 19-year old teenager, so you can well imagine my excitement at being in a movie. But the ultimate thrill for me was playing in the renowned Benny Goodman Band.

The atmosphere was energetic, and all the musicians felt like me – privileged to be in a movie as part of Benny’s band.

Busby Berkeley was flamboyant, but well-organized because there were so many people involved. To his credit, he was open-minded to everyone’s ideas.

The technique used was called ‘side lining’ where we: • Recorded the music • Listened to the playback • Applied the choreography

• Filmed the combined instrument-and-lip-sync.

The musicians were very flexible and cooperative. They felt the elaborate set designs and numbers were well-suited to the nature of the film.

The experience was all the things you could ever wish for – a perfect performance of great music.”

At the Louie Bellson website, http://www.louiebellson.info/home.html, you’ll see Bellson’s still maintaining a substantial output; a new CD from his and Clark Terry’s wonderful big band was just recently released. One particular Bellson favorite of mine is 1996’s Their Time Was The Greatest, on which Louie pays apt homage to skin-pounders from Gene Krupa to Tony Williams. Great stuff.

Above: Louie Bellson in The Gang's All Here.