The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences only got it half-right for Alien in 1980. To say that Ridley Scott’s commercial breakthrough was robbed of its Oscar for Best Art Direction/Set Direction is a pathetic understatement not only about the film in its own right, but also about the film within the history of moving-image arts. Alien did deservedly win Best Effects/Visual Effects for integrating elaborate spaceship models and grotesque creature puppetry believably into the film as a whole. Accordingly, the uncannily disturbing beast earned its place in the pantheon of movie monsters. It has actually proven so hard to look past its horrors that ‘The Alien’ is regularly acknowledged as the primary factor that immortalized the film. Yet independent of ‘The Alien,’ Scott’s vision of the future is one of the great achievements of hyper-realistic film design, released in the summer of 1979 during one of the most pivotal transitional periods between big-screen theatrical movie-viewing experiences and small-screen home-video viewing experiences. As it has become increasingly likely for a movie’s ultimate destination to be the small screen, attention to detail is less of a priority. Even if designers do commit to a high level of detail, statistically fewer viewers have an option of seeing it, based on resolution alone.

Alien is a great example of the importance of seeing movies on big screen. For any director reliant on frequent long-takes, compositions naturally become less didactic: greater scope in field-of-vision grants greater freedom to the explorative viewer’s eye. For a filmmaker like Scott, compositions are so enlarged that it is as if the audience is looking at the film through a microscope. Though Scott’s cutting is relatively quick given the film’s many scenes of action, viewers are capable of catching glances of its very DNA, almost subliminally. I have probably viewed Alien 20 times, yet below are a few details I glimpsed for the first time at a screening at New York's Film Forum’s brand new print of Alien (screening in honor of the film’s 30th Anniversary (July 10th-16th).

Simply, an attractive beer can label, probably created just for the film. Blade Runner’s universe was filled with liquor labels, neon advertising signs, and magazine covers designed just for the film even though many never even made it onto the screen. Also note the presence of fresh fruit aboard Nostromo.

A particular cigarette pack, personal photo and hand-written notes on duct-tape decorate Kane’s section of dashboard. Ergonomics in the workplace. The employee outfits his desk with souvenirs, remembrances, and reminders for comfort.

I’d noticed the pin-ups plastered on the bathroom wall several viewings ago, appropriate for a movie already filled with symbolism about reproductive and sexual politics, but the casual misogyny of a cherry pie placed over one model’s crotch and gendered genital violence implied by an otherwise inexplicable photo of fried eggs speak volumes as Ash attempts to kill Ripley by choking her with a pornographic magazine.

Cracked leather upholstery, just like in my family’s crappy old Buick when I was a kid. Of course it’s clear from the start that the Nostromo is a dump, but this is a really nice touch.

![]()

I became repeatedly aware of the signage aboard the Nostromo. The universal language of icons designed specifically for the film is meant to be instructive to crews of any language, but this particular icon is the most intriguing and the only to feature a representation of man. It is open wide for interpretation, but what I took from it is “Herein lies life in hibernation.” Who did the designer have in mind to communicate with? Is it a sign intended to instruct any variety of international Earth crews who might operate the Nostromo for 'he Company.' Or, presaging developments in the script, is it intended to be instructive for an intersecting crew, human or otherwise, about how to release the employee’s aboard the Nostromo from their frozen state if discovered. Will that intelligent life view the depicted body as a representative of thinking, feeling individual beings to meet and interact with. Or will it view the depicted body as a special territory to inhabit and conquer? Given the events of Alien’s most famous scene, the icon of a supine human body with an arrow of exploding energy from its torso gains a new, terrible quality.

Above: The Arecibo Message explained and the "distress" signal deciphered.

Alien punishes the potentially naive trust implicit in broadcasting our location via universal languages. Released only 10 years after Apollo 11 landed on the moon, the film paranoiaclly questions the prudence of space exploration and poses the risks of misinterpreted communications. Trust was the belief in 1974 when the Arecibo Message was transmitted to establish contact with extraterrestrial intelligence. However, trust fails the Nostromo whose computer system ‘Mother’ wakes the crew to respond to a presumed “distress” signal. Only too late does Mother decode the message as a warning signal. Even the design concept behind Saul Bass’ (uncredited) opening titles transforms the viewer’s initial perceptions of something seemingly benign into an understanding of a thing that is concretely threatening.

***

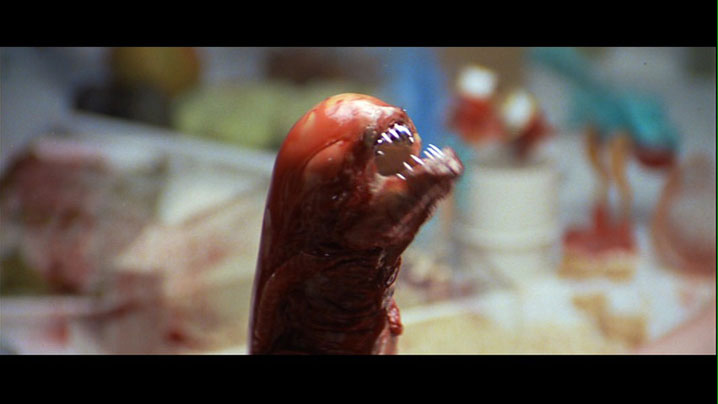

In opposition to the idea that human spirituality is a relic atrophying since its millennia-old origins with world religious figures, science fiction texts such as Arthur C. Clarke’s Childhood's End and his collaboration on 2001 with Stanley Kubrick used the allegory of alien contact to optimistically posit that mankind’s great spiritual enlightenment still awaits us. Alien agrees that major changes lie ahead for the species but paints a dark speculative fiction of evolutionary obsolescence, changes impossible for us to relate to, comprehend, or accept because they operate upon a moral compass unrecognizable by us or in direct opposition to our well-being. Early drafts of the script explicitly evoke the hostile takeovers of the natural world via a speech by Ash about the habits of parasitic wasps who lay their eggs inside hapless caterpillars. This insectoid behavior seems cruel, but maybe the relationship needs to be viewed after a shift in perspective. As David Cronenberg (who insists Shivers was a major influence on Dan O’Bannon before he wrote Alien) has pointed out in interview with Chris Rodley, the transmission of a venereal disease may initially seem a tragedy for the human host, but for the disease, it marks a successful accomplishment. Science’s development of the microscope and the telescope and subsequent observations attained via these new tools have dispelled many myths, both comforting and destructive, that were accrued from years of misinformed and inadequately lensed observations, but in Alien, the crew’s admirable explorations lead to a nightmare close encounter that emphasizes how destabilized the understanding of our own significance in the universe has become.

***

Manohla Dargis: “Scott’s lonely worldview…the chilled-to-the-bone fear that no one can hear you scream, no matter where you are.” A stripped-down visualizing of isolation, even within a clear framework of measurable coordinates.

The thirty years since Alien's release have seen the film’s own metamorphosis in a critical sense from Hollywood blockbuster to Hollywood “classic," and ultimately, with 2004’s reassessments surrounding “the director’s cut” release, into an exemplary piece of existentialist popular art. I think Alien might actually be more antagonistic than that evaluation implies. The horror of the film is not just that we each exist in isolation without any prescribed destination in a universe that has no inherent meaning (with all due respect to whatever freedoms that scenario may also entail), but that there is meaning of our lives and it is to provide a stepping-stone towards a destiny we actively disapprove of yet are unavoidably complicit in by biological determinism. If the "The Alien" overcomes, the entire history of human propagation amounts to nothing more than an abundant and wide-ranging food source. The once-comforting concept of the “circle of life” becomes viewed with a bitter sense of betrayal if we discover that our private body is nothing more than one unit of fleshy turf in a larger migratory biomass that is up for grabs. The transaction will render our hitherto proudly upheld individuality an insignificant illusion…quite painfully, I might add.

Above: On-flight computer “Mother” reveals to her ward, Ripley, that there has been a shift in the species’ priorities. Colonization of the anthrosphere is offered up to the superior breed.

Part of lasting intrigue of Alien is the friction between some of its deeply nihilistic concepts and its undeniable nature as a blockbusting, box office record-breaking, summer popcorn flick. That unique blend can be credited to collaboration rather than the vision of a single auteur. Early in his career, Scott was consistently excellent at (or perhaps just unbelievably lucky about) bringing together unsurpassed design teams who could go even beyond his already considerable strengths as a “commercial director,” in the literal sense of the term. He came from a very successful background in television commercial direction, and as a result the opening sequence of each his best films (Alien, Blade Runner, and Legend) stunningly establishes mood while smugly acting as a commercial for itself and its sets, announcing “A Ridley Scott Immersive Experience!” (with all the technically inimitable stylistic perfection and cost that that implies). I would mean that more flippantly if the results weren’t so damnably effective at yielding some of my all-time favorite movies.

Above: A Ridley Scott “money shot” from Alien's 7-minutedialogue-free introduction: beginning, middles, and end through the corridors of the Nostromo (film set) in a fluid 60-second single take.

Even if Scott cared more about directing his sets than his actors (as Harrison Ford reportedly said regarding Blade Runner), he still took a ballsy risk for a Hollywood release when he took Dan O’Bannon’s recommendation to invite Swiss sadomasochistic artist H.R. Giger aboard the film’s design team. With the headlining creature’s shape and appearance still totally undefined in pre-production, Scott knew immediately upon reviewing Giger’s book Necronomicon that he would not just be hiring an artist but moreover a philosophy. The inevitable result is that philosophically, Alien belongs to Giger as much as it does to Scott. As Edvard Munch said, “I have no fear of photography as long as it cannot be used in heaven and in hell,” and the truly unmitigated authorial vision afforded a painter through his or her solitary work comes strikes out instantly from Giger’s dark, obsessive considerations of sexual reproduction as an ancient and arcane biological technology whose machines wear out after their purpose is served. Giger examines these facts of life with a degree of coolness that is almost inhuman and that pumps his unmistakable chill into Alien. If the man has communicated directly with Satan, I would not be surprised.

Above: Giger's "Landscape XVIII" and "Necronom IV"

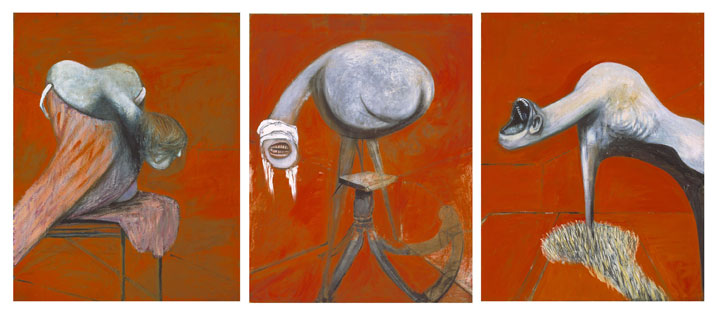

There’s unsurprisingly no Giger retrospective coincidently happening in New York to capitalize on Film Forum’s weeklong run of Alien, but the painter is not without his own “body horror”-obsessed modernist precedents. If you have the chance, I suggest you seize the opportunity for a rare Lo-Art/Hi-Art double-bill: see Alien on the big screen and then head up to the Metropolitan Museum of Art for the Francis Bacon exhibit “A Centenary Retrospective.” It might as easily be titled “In space, no one can hear you scream.” If you’re looking for a great cheap date this weekend, The Met operates on suggested donation, so you can get in for as little as one cent, and I’ll wager neither of you will feel like eating afterwards, so you can forget the dinner bill. Either your date won’t ever talk to you again or otherwise you’ll never stop clutching each other till the end of your lives.

Above: Bacon's “Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion,” ca. 1944.

***

"My painting is not violent; it’s life that is violent.” —Francis Bacon

http://www.arkive.org/large-white/pieris-brassicae/video-16.html