The 2020 special edition of the Locarno Film Festival, deemed For the Future of Films, gathers audiences in both virtual and physical space. At the center of this year's festival are 20 suspended projects, each halted in some way by the COVID-19 pandemic, that will compete in the The Films After Tomorrow section.

From Lisandro Alonso and Miguel Gomes to Lav Diaz and Lucrecia Martel, these 22 filmmakers have also joined together to handpick twenty films from previous editions of the festival. The program, A Journey in the Festival's History, is an anthology of timeless films from Locarno's past (from 1948 to 2019) that reflect the festival's spirit of discovery and celebration of stylistic breakthrough. MUBI is immensely proud to be partnering with the festival to make these selections available for streaming outside Switzerland. Below, the directors have shared some words about their inspired choices.

Wang Bing on Horse Money (Pedro Costa, 2014)

Pedro Costa’s films explore colonial history and reflect on its relationship with our modern world. He has developed his own pure, original narrative style and has remained constant to it, creating films of profound sincerity.

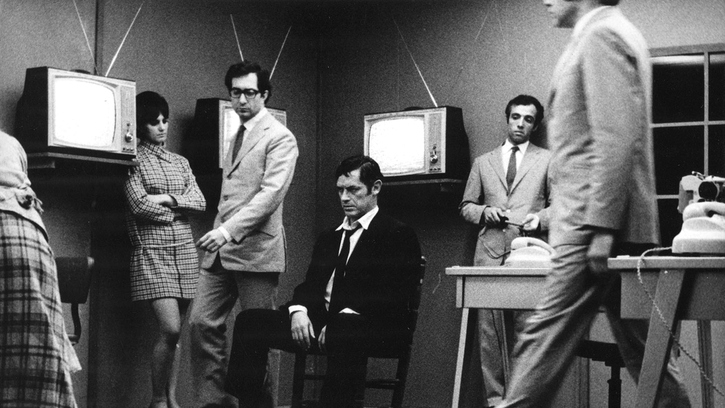

Mateo Ybarra & Raphaël Dubach on Charles mort ou vif (Charles, Dead or Alive) (Alain Tanner, 1969)

"I feel as though I’m wrapped in cotton wool. With no real anxieties. With no hope. Locked up in comfort and safety." Charles Dé is the head of an important, austere family business. On the day of the company’s 100th anniversary, he realizes his bourgeois, capitalistic lifestyle is the polar opposite of his erstwhile passions. In the midst of an existential thunderstorm, he decides to break completely with this universe and live on the edge. He then encounters Paul and Adeline, a bohemian couple with whom he shares a free-spirited existence in the Geneva countryside. Tanner’s film has the energy and strength, but also the fragility of a debut film. Renato Berta’s cinematography is raw; François Simon’s performance is jarring. Most of all, though, Charles, Dead or Alive is a cinematic manifesto, with the energy of May ’68, where one dreams of Lake Geneva becoming a harbor as dark as coal, with black barges, where a car is launched from the heights of a gravel quarry; where one expresses their malcontent by spitting potatoes; where Swiss prosperity is criticized in a school poem. In paving the way for new Swiss cinema with sensitivity and irony, Alain Tanner described the sparkling energy of a time period where everything had to be deconstructed. Therein certainly lies the affection we have for this film and for Tanner’s work: poetry as an act of subversion.

Anna Luif on Love Meetings (Pier Paolo Pasolini, 1964)

For Love Meetings (1964), Pasolini travelled around Italy and asked Italians questions about love. He asked students about the equality between men and women, he asked soldiers about being a Don Giovanni or a family man, he asked farmers about now and the past, he asked poor and rich people in the streets and on the beaches of Veneto, Calabria, Tuscany, etc. about divorce, homosexuality, sadism and masochism and he asked prostitutes about the Lex Merlin (a law that declared brothels illegal in 1958). In beautiful black and white frames, we see the well-dressed Pasolini – most of the time from behind – with a microphone in his hand in the middle of large groups of people. We hear his relentless voice asking and repeating simple questions like “Do you think marriage solves all sexual problems?” and then we watch: the faces of all types of people (young, old, rich, poor, beautiful, ugly, confident, shy) trying to answer Pasolini’s questions. The longer I watch this highly entertaining and extremely interesting period document, I ask myself how Pasolini must have felt amongst the Italian people answering to almost all his questions with answers that went against his own values and convictions. And I imagine how lonely Pasolini must have felt. A man, who in his films and writings treated themes like the love and sexuality between mother and son, the killing of one's own child, violence, purity and religion, etc. And it always strikes me how extremely brave this artist has been and how much we (I) can still learn from him.

Lav Diaz on The Seventh Continent (Michael Haneke, 1989)

I can’t remember the exact year I saw this film, Michael Haneke’s first film. But I know it was during the mid-nineties, so it could be around 1994, 1995, 1996 or 1997, in New York City. It was all toil, toil and dream for me then, art and otherwise, with the city’s underbelly, underground, and with the understanding, at least in my head then, that no matter what, I shall end up, one day, doing cinema. I was doing three or four jobs, the desk job with a Filipino newspaper being the main gig, and the money from it I was sending to my family in the Philippines, and on the side, I was doing odd jobs for survival and more importantly, for the pursuance of cinema, so to speak, the money spent for the procurement of those very expensive 16mm rolls. The in-betweens, during the so-called free periods and freer times, were spent on watching a lot of cinema; and truckloads of rented VHS was my cinema diet then. I remember having the scariest feeling after watching The Seventh Continent; that I remember clearly even today; it was a deadly cold winter’s night and I went for a real good, strong coffee and dirty cheesecake from my favorite Catholic Arab deli. The scare I got wasn’t anything like the cliched ‘horror-trip experience’ one gets from the genre but deep in this film’s simplicity and mystery, there was an exactness in its engagement of real life’s horrors, and it is just that—that life itself is the horror, or YOU are the horror. Pessimism is an essential truth in this film, and it’s up to you if you’ll accept it. There is no escaping this hell called life. I accepted it, but not in resignation.

Michael Koch on E Nachtlang Füürland (Land of Fire All Night Long) (Clemens Klopfenstein & Remo Legnazzi, 1981)

E Nachtlang Füürland (1981) is a restless odyssey through the nightlife of Bern in 1981. Max Rüdlinger plays a wonderfully comical, worn-out newsreader who has become very disillusioned but instead of changing his life, has made himself comfortable in the role of the unhappy grumbler. He drifts from bar to bar during an ice-cold winter night in Bern and finally meets a woman with the opposite energy. For one moment the possibility of change beckons—at least for a brief moment everything seems possible again. Almost casually, the camera follows the protagonists and captures the feverish excitement of the night. In a mixture of discovered situations and planned encounters, one sees Max Rüdlinger and some non-professional actors improvising through the night. The film is both a document of the times and a beautiful, always surprising, authentic, strangely funny portrait of a group of people. Even though the dialogues are not always equally well improvised, the film has an incredible freshness, freedom and energy that fascinates me. Shot on film, E nachtlang Füürland also demonstrates that every film lives through its performers, from their faces and characteristics. The characters' faces carry this film. There are little moments, unpolished scenes, such as the speech of a woman in a bar talking about her fight for a little freedom as a mother and housewife with an energy that blows you away.

Pierre-François Sauter on Germany, Year Zero (Roberto Rossellini, 1948)

With Germany, Year Zero Roberto Rossellini chooses to show the damage caused by Nazism. And he does so with great ambition: shooting this film in 1947 in the real settings of ruined Berlin, two years after the end of the war. This film is not without flaws, in certain aspects it is dated, but it is a film that impressed me by the economy of its narration and by the strength of the quasi-documentary sequences shot in apocalyptic settings, which echo his point. Against this ruinous background, which evoke the violence and horror of war, Rossellini films a world that has suffered total destruction, both materially and morally. He shows the annihilation of all values caused by Nazism. He chooses to film on the side of those who took part in Nazism and were defeated. He shows his characters as lost people, victims of their own blindness and of issues that are beyond them. Rossellini films the journey of Edmund, a twelve-year-old boy who tries to find his way in a world where profit and selfishness are the only things that matter. Germany, Year Zero is a radical and tough film that leaves no one untouched. This film continues to resonate with me, seemingly still retaining all its relevance today, as if to remind us that ideological drifts that lead to horror are always possible.

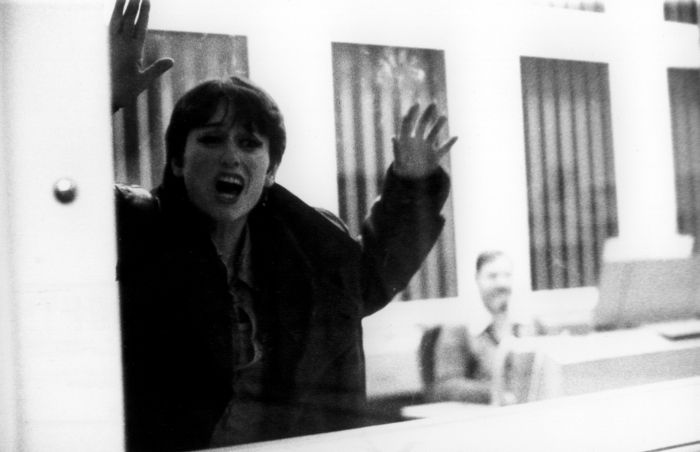

Juliana Rojas on In Gefahr und größter Not bringt der Mittelweg den Tod (In Danger and Deep Distress, the Middleway Spells Certain Death) (Alexander Kluge & Edgar Reitz, 1974)

The first time I saw a film by Alexander Kluge was during a retrospective of his work at the Brazilian Cinematheque, in São Paulo—an essential place for my training as a cinephile and a filmmaker, and that today is threatened by a lack of government investment. It was 2003 and I was still in film school. On the same exhibition I saw In Gefahr und grösster Not bringt der Mittelweg den Tod, directed by Alexander Kluge & Edgar Reitz. I felt a chill immediately from the first seconds of the projection—the movie title written on a wall of an abandoned building. The film impressed me with its vivid mix of documentary, fiction, and archive footage, articulated by fragmented and dialectical editing. It showed me how cinema could gain a political dimension and the power created when the performers confront reality and the public sphere. I still have the program from that screening with me, and to this day, when I reopen it, not only the memories from the movie emerge, but also I relive the wonderful feeling of discovering something new and pulsating inside a film theater. For me, it is an example of the power of cinema to create emotional memories and make us travel through time. Especially in these difficult times, in order to deal with the present and construct a better future, we must make this journey back to the past and learn from history—and we might be surprised at how contemporary some films are.

Helena Wittmann on India Song (Marguerite Duras, 1975)

The Indian housekeeper lights an incense stick before white society enters the decadent rooms. From outside, the voice of a beggar woman keeps pushing into the building, carried by the damp air. There's no sight of her, the beggar woman, and she will not be seen in the entire film. But one can feel her, just as one can smell the heavy scent of the incense sticks, which slowly and yellowishly blend with the sultry heat. Anne-Marie Stretter, the Venetian pianist, wife of the French ambassador to India – listless and longing – dances. She appears in a mirror, regarded by us and by one of her suitors, who watches her from all sides throughout the film. Off-screen voices recall this woman, sometimes they seem to be present in the room; sometimes they seem to conjure up the scene that we see; sometimes they report on what we don't see and what echoes into the film as "world". Sometimes it's silent, completely silent. A hand passes over her white back. One hand turns in another's. Just very lightly. In the film, it's a tremor. Time passes in loops, very dense, very sinister and very seductive. And there is this song, India Song, which is heard repeatedly, and which is danced to repeatedly, and one you will not forget so quickly.

Andreas Fontana on Invasión (Hugo Santiago, 1969)

A few years ago, I was walking through the streets of Geneva with Mariano Llinás and we started talking about Hugo Santiago. Hugo had just died and Mariano was his friend and collaborator. He was on his way to Locarno to present his own film-labyrinth, La Flor (2018). At one point during our walk, Mariano said to me: "It's interesting: everyone who has seen Invasión is convinced that in Argentina, at the end of the 1960s, people dressed exclusively in suits. Obviously that wasn't the case". That's one of the dizzying aspects of Invasión: treating the fantasy genre with such rigour that everything becomes believable. Who is Hugo Santiago? I don't know very much, just a few rumours. A young Argentinian who travelled to Paris in 1959, met Robert Bresson at Cocteau's and followed him like a shadow until he became his assistant. A young filmmaker who, when he returned home, went to find the living legend that is the writer Jorge Luis Borges to write a film—which became Invasión. A director whose precision and attention to detail was said to border on obsessive. What is Invasión? A film that has all the ingredients of a detective film, or a spy film, or a resistance film, or all of these together, but whose radical strength lies in its unsolved mystery and the incessant melancholy of its characters. I won't say any more. But in my opinion, mystery and melancholy are two excellent arguments for going to see a film.

Elie Grappe on M (Yolande Zauberman, 2018)

Passing through the list of the selected movies in Locarno Festival since 1946, my eyes stopped on Yolande Zauberman’s M. That oneletter was enough to wake up my stupor as a spectator in Fevi hall, in 2018. Enough also to bring me back to this dark beach of Tel Aviv: Menahem is facing us, shirtless. Singing with a powerful voice. Then he tells, he tells us about the rapes he endured as a child, being part of an ultra-orthodox community. Menahem is so close, he almost get out of focus, but the frame stands his gaze. He sings again; a magnificent liturgy which carries its suffering and its survival. Menahem drives us to Bnei Brak, the town of his abused childhood, where he’s comingback for the first time for ten years. He came to dissect the taboo.Other voicesopen up, following his own, in a prodigious succession of sequences.Whereasthe night seems to never come toanend, the smile and the song of Menahem irradiateeverything. Yolande Zauberman’s documentary is “a vampire movie”, a tale, a deeply heroic journey. Made of questions and paradoxes, it continues to nourish my imagination and my desire of cinema.

Verena Paravel and Lucien Castaing-Taylor on Mababangong Bangungot (Perfumed Nightmare) (Kidlat Tahimik, 1977)

The cinematic shaman Kidlat Tahimik’s film, Mababangong Bangungot, has lost none of its unerring and unnerving magic over the years. Inventing at a stroke a wholly new genre of postcolonial picaresque, the film’s provocations, both in style and in substance, are as breathtaking in 2020 as they were in 1977. Its whimsical, quixotic self-fashioning of “Kidlat,” and his peregrinations around the Philippines and Europe, as he dissects and dismantles the obscenity and inanity of North American imperialism, European crypto-colonial modernity, and neo-liberal consumerist capitalism tout court, have, if anything, only increased in their prescience and pertinence since then. The film couples comedy and critique, absurdist humor and self-deprecating irony, like no other we know. An inimitable fabulist, and mythopoetic gadabout, Kidlat wryly thumbs his nose at the racist tropes of ethnographic film, travel documentaries, and Western primitivism in a fashion that no one before had dared and no one since has essayed. Almost half a century later, the world is now on fire. Marcos’ US-sponsored dictatorship already contained the seeds of Duterte’s, and as Duterte, Bolsonaro, Modi, Erdogan, Trump and their ilk strut their shit on the world’s sickening stage, screening Mababangong Bangungot today brings home with unremitting force many of the causes of our current global crisis. Kidlat’s ludic proclamation of imaginative freedom and cosmopolitanism, “I chose my vehicle and I can cross all bridges,” clamors to be heard as never before, even as it sounds ever more like utopian wish-fulfillment fantasy.

Cyril Schäublin on No Home Movie (Chantal Akerman, 2015)

The first film by Chantal Akerman I ever saw was News From Home (1977), which connects streetscapes in New York City with letters from her mother. After watching No Home Movie (2015) in Locarno in 2015, to me, these two films mysteriously connected with each other. But to be honest, all of her films speak to me. Somehow, they go to a place beyond words, a place where things and meanings turn into something really interesting. Like in her silent short film La chambre (1972). I hope you get a chance to see it, too.

Miguel Gomes on O Bobo (José Álvaro Morais, 1987)

The 1980s were a golden decade for Portuguese film. It was a decade that began and ended with two masterpieces: Manoel de Oliveira’s Francisca (1981) and João César Monteiro’s Recollections of the Yellow House (1989). There were others, though, like José Alvaro Morais’ O Bobo from 1987. Although it won the Pardo d’oro in Locarno in that year, time did not grant him the international renown of the other two directors, and it’s a shame. O Bobo is the film that depicts the climax of Portuguese cinema’s anti-naturalistic element. It is a kaleidoscope of gestures, words, sounds, mise-en-scène, scene transitions and shot junctions. Everything is operatic in O Bobo. But there’s nothing grand about it, because it’s a comic opera. The film’s musicality, which is sensual, swinging and ironic, does not conceal the seriousness of the wounds. What is O Bobo about? In essence, it’s about faithfulness and betrayals. But it’s also about love, the city of Lisbon, theater and film, the post-revolution hangover, the founding of the Kingdom of Portugal, and the end of the Portuguese Empire. The grandeur of all that is impossible to separate from the film’s production timeline: it started in 1978 and went on for years with rewrites, reshoots, reediting and a demanding sound editing process. The sound editing in O Bobo struck me so much that I hired Vasco Pimentel as the sound engineer for my own films, after he had spent years working with José Alvaro Morais to create the incredible monaural symphony for that picture. Vasco told me he met with the director, the day after the Locarno awards ceremony, to write new dialogue for O Bobo. After they returned to Lisbon with the prize, they kept working on the film, which wouldn’t premiere until 1991, 13 years after the end of principal photography.

Lucrecia Martel on Rapado (Martín Rejtman, 1992)

Rapado (1992) premiered in Buenos Aires in 1996. I had heard about the film because some friends had worked on it, an absolute privilege in a moment in which young people were not shooting films. Even before watching it, the film was already an important milestone for us who were interested in telling stories with film. So I went to a Rapado screening and for the first time, cinema was not something foreign to me. That feeling of generational proximity gave in to a much more elaborate and intense way of seeing the world, finally looking like the world and not trying to impose a mediocre idea of realism. In the film, the intentions of the characters would flounder and the usual consequences of their actions would fade away. The perfect sexuality that I was not achieving in my personal life and that films portrayed constantly, was also failing in Rapado, projecting its beauty on the more eccentric and weird people. At last, people were interesting. Life without epics was an extraordinary adventure. And so was language. Years later, I met Martín Rejtman during a film festival while he was showing his second film—Silvia Prieto (1999)—and immediately asked about that particular way of speaking that his characters have. He replied something that I could never confirm: "the spoken English in North American cinema is an invention, a language that is not spoken anywhere". I may be misquoting him, but that was what we needed to do: invent Spanish for cinema. Of course, he did it. Martín had tried out his invention in Rapado and those sounds had announced the arrival of a new film generation. I chose this film because it's beautiful but also to share Rejtman's conviction, that is now also mine, on inventing the sound of the characters.

Marí Alessandrini on Stranger Than Paradise (Jim Jarmusch, 1984)

Unhealthy, lonely, soulless comfort... welcome Eva to paradise! Being a foreigner or stranger is expressed as an immutable condition in this paradise called North America, where disinherited young people end up being "neither from here, nor from there". Willie, a card player in depression, who has been living for ten years and has adapted in his way to New York, takes in against his will his young cousin from Budapest, Eva. Strangers in Paradise (1984), it is a spiral breakout, from New York's Lower East Side, through the harsh winter of Lake Erie to the decaying beaches of Florida. A major work of cinema of the 80s with contemporary composition, where Jim Jarmusch captures with ironic and laconic poetry, the unleashing of disillusionment and disconnection of these three uprooted young people. A monochromatic road movie that advances in the mist, discovering that in "The American dream" for Willie, Eva & Eddie there is nothing to discover.

Eric Baudelaire on The Terrorizers (Edward Yang, 1986)

The Terrorizers (1986), by Edward Yang, ends with a woman turning away from her bed companion and vomiting. Not quite, actually: the credits roll before any vomit appears—just the retching sound, and then the credits. It is one of my favorite film endings. It is also one of my favorite titles (especially its mysterious plural, because notallthe protagonists in the film fit under the category of terrorizer). The film is a non-linear, fragmented self-portrait of the artist projected onto the landscape of Taipei—the artist as novelist searching for her voice, as photographer stalking a reluctant muse, as adolescent girl honing her skills as a scam artist. These and other characters leap into simple, essential, often frontal shots of city streets and buildings, forming a narrative and architectural mosaic that is both splendidly poetic and politically acute. Few films create their own unique worlds with such an economy of means: a way of framing, a few very spare and unique personal misadventures, and a nod to various codes and genres (the police thriller, the romantic drama, the “Roman photo”). There are films you watch and never forget. This one’s strength somehow works the opposite way for me: I forget all of its details every time I see it, I just remember how much I liked it. When I see it again, all the pleasure of discovering it remains intact: an ode to complex simplicity.