Say what you will about Todd Phillips Joker but its production design is on point (making it all the more remarkable that one of the film’s 11 Oscar nomination was not for Mark Friedberg’s stellar work). The film seems to be set in a late ’70s, early ’80s New York (a.k.a. Gotham) when the city was at its grittiest, somewhere vaguely in between the New York of Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver (1976) and the New York of Martin Scorsese’s King of Comedy (1982), the two films that Joker shamelessly tips its green wig to. In actual fact, however, it turns out that the film is set in a very specific time, namely the last week of July 1981. But more of that later.

Unsurprisingly to anyone who reads this column, I love movie posters within movies and I love movie marquees. Joker opens and closes with a couple of Times Square-esque marquees for fake porn films: Strip Search and Ace in the Hole. Both of the scenes these marquees appear in were actually filmed in Newark, which still retains the grittiness that can no longer be found in present day Times Square. The opening sequence, in which Arthur Fleck twirls his prophetic Everything Must Go sign beneath the marquee of the “Newart Theater,” was shot outside the still-standing Paramount Newark theater which opened as a vaudeville house in 1886 and closed a hundred years later (five years after the events of Joker). For the production the Ks of “Newark” were removed and temporarily replaced with Ts (and according to eye-witnesses this was done physically not digitally).

The climactic scene of the film (mild spoiler alerts follow) in which clown-masked rioters tear the city up, takes place in front of a fake marquee which Friedberg created on Market Street in Newark, promoting the equally fake (at least as far as my extensive research into early ’80s porn can tell me) Ace in the Hole (“in 3 acts”) which is clearly not a revival of the Billy Wilder film.

The least convincing movie-within-the-movie in the film is the black tie screening of Charlie Chaplin’s 1936 Modern Times at Wayne Hall (actually the Hudson County Courthouse in Jersey City) which just gives Phillips an excuse for Arthur Fleck to enjoy Chaplin’s insouciantly daredevil rollerskating scene (a scene which employed matte paintings as deftly as that long shot of the city at the top of the page).

But the scene which firmly sets Joker in the last week of July 1981 is the sequence towards the end showing Thomas and Martha Wayne and their son Bruce leaving a movie theater (in reality the Loew’s Jersey Theatre in Jersey City—one of the five Wonder Theatres opened by Loew’s in the late 1920s) in the middle of the riot. The marquee clearly touts Brian De Palma’s Blow Out and Peter Medak’s Zorro, The Gay Blade, both of which opened in New York on July 24, 1981.

As the camera dollies past the front of the theater, beneath its gorgeous marquee lights, we get blink-and-you’ll miss them glimpses of four movie posters (click on the images to see them large). First Blow Out:

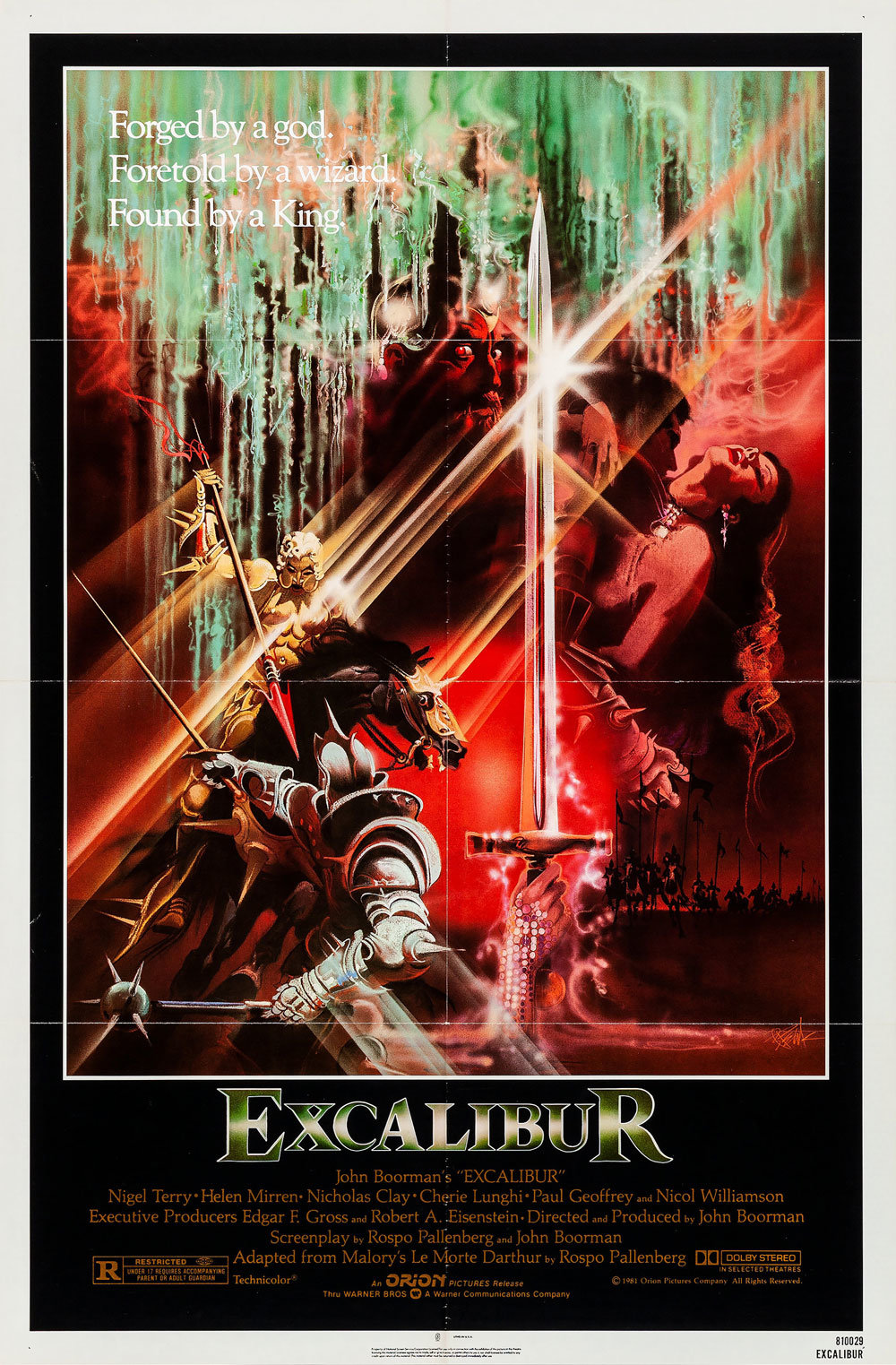

Then Bob Peak’s poster for John Boorman’s Excalibur, which is somewhat the odd man out because Excalibur opened three months earlier on April 10, 1981.

And then, if we’re not too distracted by the Waynes leaving the theater (which film had they just been watching?), we can glimpse a poster for the Dudley Moore comedy blockbuster Arthur, which had opened a week earlier on July 17, 1981.

The tagline for Arthur could have served as an ironic tagline for Joker.

And finally, around the corner, down a dark alley, we see the poster for Michael Wadleigh’s werewolf movie Wolfen, which also opened the same day as Blow Out and Zorro.

Blow Out, Wolfen, and Zorro were all reviewed in the Friday July 24 edition of the New York Times, and ads for all three, as well as for Arthur, appeared in the same paper.

What’s remarkable is how little screen time these posters get and yet how carefully Phillips and Friedberg planned their inclusion. Not only do the posters fix Joker’s climax in a very specific time, they also speak to the film itself. I can’t see the connection with Blow Out, but Excalibur and Arthur are both about a man named Arthur, as is Joker of course, and Wolfen is a transformation-centered, New York-set horror movie, much as is Joker. The comedy Zorro, The Gay Blade might seem an odd choice until you read the synopsis which tallies with Joker’s themes of wealth and class: “When the new Spanish Governor begins to grind the peasants under his heel, wealthy landowner Don Diego Vega follows in his late father's footsteps and becomes Zorro, the masked man in black with a sword who rights wrongs and becomes a folk hero to the people of Mexico.”

There are no posters within the film for Scorsese films, even though the film otherwise wears its Scorsese references proudly, but on July 24, 1981, there was one Scorsese film playing in New York: a revival of New York, New York, which, just coincidentally, is being revived in New York again, starting today.