An allowance for irrationality forges the difference between a shrewd and a calculating eye. This arrangement (of facts, of phenomena, of the empirical) is what makes good science; it’s what raises science from bad poetry to something like an art. Samuel Fuller made a life training his eyes after this fashion, to see what we don’t want to see. Nobody in America wanted to see White Dog when Fuller made it in 1982—at least nobody in the studios wanted to let loose this feral thing on anybody in the public for fear of all the possible reactions it might and it can and it does elicit. Because as pointed as its argument may be—as agitpulp—Fuller’s White Dog, like anything (like a dog, say), may be seized for undue or unwanted or unethical purposes.

An allowance for irrationality forges the difference between a shrewd and a calculating eye. This arrangement (of facts, of phenomena, of the empirical) is what makes good science; it’s what raises science from bad poetry to something like an art. Samuel Fuller made a life training his eyes after this fashion, to see what we don’t want to see. Nobody in America wanted to see White Dog when Fuller made it in 1982—at least nobody in the studios wanted to let loose this feral thing on anybody in the public for fear of all the possible reactions it might and it can and it does elicit. Because as pointed as its argument may be—as agitpulp—Fuller’s White Dog, like anything (like a dog, say), may be seized for undue or unwanted or unethical purposes.

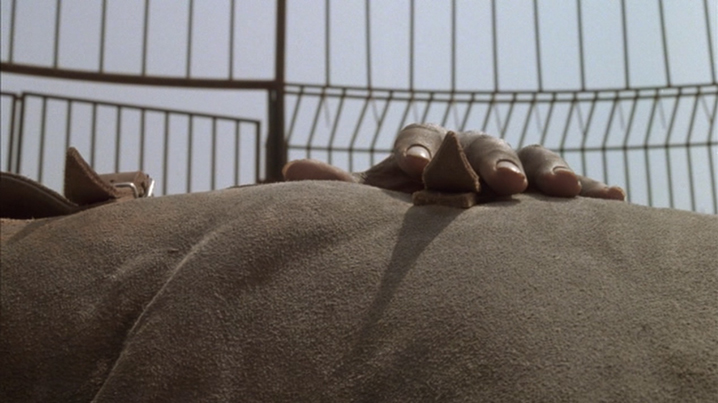

The lead: young actress Julie Sawyer (Christi McNichol) hits an unleashed, white German shepherd in the Hollywood hills with her cream Ford Mustang. After a costly visit to the vet, Julie takes the pooch into her home and a night later he saves her from rape during a home invasion. Yet Julie does not know that this white dog is not simply a best friend. She soon learns he is rogue, prone to flight, as he runs after a rabbit away from her house. During his brief sojourn/escape, we witness the white dog attack and kill a black street sweeper operator, whose corpse drives into a high end boutique, breaking mirrors and mannequins. Following the dog’s bloody return, Julie learns it attacks—ferociously, to the bone—while shooting a commercial, when the beast jumps on Julie’s black friend and colleague, Molly (Lynne Moody), and we see the pattern emerge (as if the film’s title, and grayscale credit sequence, didn’t clue us into the problem of color). It takes another unforeseen, yet thankfully muzzled, blitz for Julie to recognize the specific threat this dog presents. Burl Ives plays Carruthers, owner of Noah’s Ark, a farm for training wild animals, and post-assault he barks in turn: “That ain’t no attack dog you got; that’s a white dog!” Julie thinks he’s talking fur, but he corrects her (again): “I don’t mean his color: he’s taught to attack and kill black people!” Enter, via zoom in and pull out, Paul Winfield’s Keys. Yes: he’s here to unlock the trap of racist eyes, to unmuzzle this beast of hate, to turn that snarl into a slobbering smile, if such is at all possible. Fuller’s hyperbolic ALL CAPS sensibility, for humor as much as for so-called humanity, saves all this (all his films) from the possibility of devolving into a soapbox statement/thesis. It’s a weird move, really, and tough to pull off with any grace—but that’s just it: Fuller denies grace. The edits and the angles and the performances and the dialogue, all his materials, remain rough to the end. Yet, his vision is not simple cynicism; rather, he sees the world as stew, a bog of trained idiocy, and all we can do is form tactics for survival. It’s all about trying. Try Keys does. After his delayed introduction (about 30 minutes), White Dog becomes his movie, not Julie’s nor the dog’s (as much as the film is always all about the dog), and we watch this strong and contradictory man work to make things right one experiment at a time.

Fuller’s hyperbolic ALL CAPS sensibility, for humor as much as for so-called humanity, saves all this (all his films) from the possibility of devolving into a soapbox statement/thesis. It’s a weird move, really, and tough to pull off with any grace—but that’s just it: Fuller denies grace. The edits and the angles and the performances and the dialogue, all his materials, remain rough to the end. Yet, his vision is not simple cynicism; rather, he sees the world as stew, a bog of trained idiocy, and all we can do is form tactics for survival. It’s all about trying. Try Keys does. After his delayed introduction (about 30 minutes), White Dog becomes his movie, not Julie’s nor the dog’s (as much as the film is always all about the dog), and we watch this strong and contradictory man work to make things right one experiment at a time.

What’s really cool is that, on some elemental level, Keys' experiment with this white dog (ahem, the film) is all about seeing—or, training-teaching the dog (ahem, us) to see. What’s troubling is that this attempt to recover sight proves unnatural, despite the leaps Keys makes, and prone to reversal as much as education; the danger of reification as much as the danger of fangs. But, again, this isn’t a tired sociology problem with no answer, just some set of “facts.” No, White Dog, like its maker, may remain stained and scarred, like our country, but it doesn’t shut down the argument in platforms or any banal (naïve) humanism of the common (which is supposed to, I’m continually guessing, sprout understanding? —always seems to me like a pat on the back). Rather, Fuller offers, as Armond White writes inside the package’s booklet, a “humanitarian vision,” which, of course, is about seeing the world beyond us silly beings (with our lenses and our prejudices, our ability to destroy more often than build); a sight that aims for harmony in thoughtful hope, that may produce a better planet with better lives for trees and dogs and elephants alongside our nigh despotic dominion (with our boulevards and our words, our farms, our factories and our lynchings). Naturally, the natural is an illusion, or at least a question, if ever a function of the world. Colored with tenderness by Ennio Morricone’s dulcet piano score and gauzed by Bruce Surtees’ breezy (yet tight) camera work, White Dog never purports to possess an answer, but it does try to live, and it does proffer the one thing that may elevate our species: an education (which is, as can only be natural, a perpetuity and not a boundary) on, among other things, how to see the inutility of willful ignorance.

What’s really cool is that, on some elemental level, Keys' experiment with this white dog (ahem, the film) is all about seeing—or, training-teaching the dog (ahem, us) to see. What’s troubling is that this attempt to recover sight proves unnatural, despite the leaps Keys makes, and prone to reversal as much as education; the danger of reification as much as the danger of fangs. But, again, this isn’t a tired sociology problem with no answer, just some set of “facts.” No, White Dog, like its maker, may remain stained and scarred, like our country, but it doesn’t shut down the argument in platforms or any banal (naïve) humanism of the common (which is supposed to, I’m continually guessing, sprout understanding? —always seems to me like a pat on the back). Rather, Fuller offers, as Armond White writes inside the package’s booklet, a “humanitarian vision,” which, of course, is about seeing the world beyond us silly beings (with our lenses and our prejudices, our ability to destroy more often than build); a sight that aims for harmony in thoughtful hope, that may produce a better planet with better lives for trees and dogs and elephants alongside our nigh despotic dominion (with our boulevards and our words, our farms, our factories and our lynchings). Naturally, the natural is an illusion, or at least a question, if ever a function of the world. Colored with tenderness by Ennio Morricone’s dulcet piano score and gauzed by Bruce Surtees’ breezy (yet tight) camera work, White Dog never purports to possess an answer, but it does try to live, and it does proffer the one thing that may elevate our species: an education (which is, as can only be natural, a perpetuity and not a boundary) on, among other things, how to see the inutility of willful ignorance.

Our history is unavoidable, and alive, and White Dog, like our President-elect, isn’t about a simple tolerance, a naïve assimilation of the pleat. This country takes work. The myth costs us every day. What is asked: share the load, asshole, and don’t give up—I haven’t yet. For some, this appeal of looking beyond (if not beneath) race in an effort to recognize the singular troubles consent—and it always will—but if our season has a lesson for us it’s that, well, fuck yes things can change. But remember the past, and the cost, that today carries. We step forward together, sure, but people are dangerous and petty and after cash and securing their own before the good of the rest so watch out. There are fewer Keys than white dogs; fewer Fullers than shills; fewer films than commercials; fewer things to believe in, like hope, than those to disparage. Yet here we are, living, writing our way forward. I cannot believe this film is as old as I am. J. Hoberman contributes an essay to the booklet as well, calling the film “a genuine cause célèbre,” and we must thank Criterion for their beautiful, stark edition. Closing his essay, Hoberman writes, “What’s stunning about Fuller’s two-fisted allegory is how White Dog gives race hatred both a human and subhuman face. This terrific movie is even more remarkable than the travails it suffered on the road to recognition.” I couldn’t agree more. The disc contains a 40-something minute “documentary” on the production history of the film, if you’re into that sort of thing, plus some great on-set photos, but the real treasure lies past the typically sterling essays by Hoberman and White in something Fuller penned, in 1982, for issue 19 of the journal Framework: an “interview” with the titular star of the film, our white dog. I think this exchange sums it up:

J. Hoberman contributes an essay to the booklet as well, calling the film “a genuine cause célèbre,” and we must thank Criterion for their beautiful, stark edition. Closing his essay, Hoberman writes, “What’s stunning about Fuller’s two-fisted allegory is how White Dog gives race hatred both a human and subhuman face. This terrific movie is even more remarkable than the travails it suffered on the road to recognition.” I couldn’t agree more. The disc contains a 40-something minute “documentary” on the production history of the film, if you’re into that sort of thing, plus some great on-set photos, but the real treasure lies past the typically sterling essays by Hoberman and White in something Fuller penned, in 1982, for issue 19 of the journal Framework: an “interview” with the titular star of the film, our white dog. I think this exchange sums it up:

Fuller: You’d have been shot if you attacked him.

Dog: Me get shot for giving that bastard a taste of my fangs?

Fuller: That’s right.

Dog: What the hell are you talking about? Why shoot me? He’s the bastard who made that dog into a racist.

Fuller: How the hell would you prove that?

Dog: I guess you’re right.

Fuller: I know I’m right.

Dog: Your laws are rigged, you know that.

Fuller: Yes.

Dog: Doesn’t your world make you want to vomit?

Fuller: Sometimes.