THE THREE FACES OF EVE

I tre volti (Three Faces of a Woman, 1965) is, among other things, the Antonioni film you're least likely to have seen, the Bolognini film you're least likely to have seen (a larger field) and possibly the only Franco Indovina film you ought to see. It is, as you'll have guessed, a product of that swinging sixties' fad for auteur smorgasboards, compendium films comprising various shorts by various directors, typically including a few great directors collecting their cheques and a couple of up-and-coming nobodies to pad out the numbers. These directorial scrimmages are a bane to collectors, since they're rarely made available on home video. We're fortunate that Truffaut's episode of Love at Twenty has been released as a short in support of the Baisers volés DVD, but what if we want to see the Wajda? Fellini's episode of Boccaccio '70 has long been impossible to see with English subtitles, despite its featuring the iconic image of a fifty-foot-tall Anita Ekberg, a humanoid summation of the maestro's entire oeuvre.

But there seems to be more behind the unavailability of I tre volti. Rumours persist that the Iranian secret police once travelled the world, buying up all prints of this arthouse flop, and burning them, until the Cinematheque in Rome housed the only known surviving copy...

THREE FACES EAST

An astonishing vanity project, or a colossal tax write-off, the film's origins lie shrouded in mystery, and are likely to remain so until someone can get a straight answer from producer Dino DeLaurentiis about what he was thinking of. In other words, we will have to wait until the end of recorded time.

The film's "star," Soraya, around whom the whole thing is constructed like an elaborate gown, had recently divorced the Shah of Iran (hence, perhaps, those rumoured print-destroyers) and was well-known as a jet-setting fashionista. Antonioni, for reasons known only to himself and his business manager, directs a segment designed solely to accustom us to the absurd idea of Soraya making a movie. It's a sort of airlock we have to pass through before entering the depths.

Paparazzi eagerly wait the Great Lady's arrival at a a studio situated amid a maze of strip-lit driveways. An array of wigs is laid out on disturbing foam heads. The star arrives in a blur of limos and handlers and the lighting malfunctions around her as if her mere presence were so stellar as to interfere with the flow of electrons.

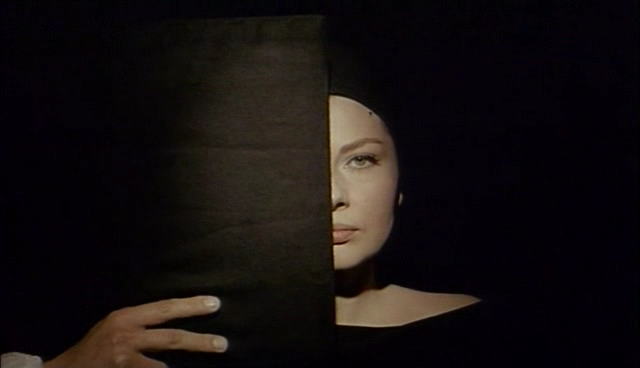

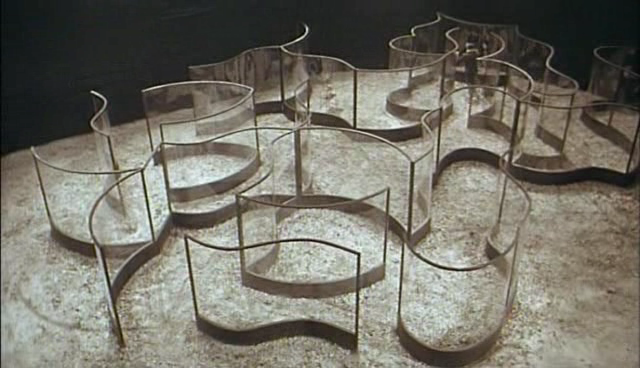

In a dressing room, we watch the diva transformed from a shiny, frowning millionairess into an immaculately made-up, frowning millionairess. Ushered before the cameras, the divine pseudo-empress receives a phone call from a man in a perspex maze, whose apparent purpose is to illicit emotional responses for the camera. "Things to make you laugh, things to make you talk." She doesn't laugh. She barely talks.

At this moment, two things become clear. The story has no point, and Antonioni is nevertheless doing his best with it. The visual tropes we find in his serious works, freed from the necessity of somehow connecting, however elusively, with theme or narrative, are allowed to run riot, although they can only get so far until pulled back down to earth by the utter pointlessness of the entire exercise, and the fact that Soraya has less screen magnetism than the bit of wood drifting across the surface of a drum full of water in L'eclisse. Seriously, it's not even close.

THREE FACES OF FEAR

Next, Mauro Bolognini steps up to the plate (of congealing ravioli). A less-respected director than Antonioni, he manages a better start, with guests in tuxedos and gowns wandering disconsolately in the dawn aftermath of a party at the Parthenon. He attempts to compensate for Soraya's flat screen persona by thrusting Richard Harris up against her. Harris can smolder for two. He's cast as a poet and novelist struggling with that difficult second book, and distracting himself with the Italian high life. In other words, he's Stanley Baker in Joseph Losey's Eva. Bolognini and co-scenarists Tullio Pinelli and Clive Exton have simply torn the character out of Losey's scenario and pasted him into theirs'. Although they show the character disgracing himself at an awards ceremony, a scene clearly inspired by Harris's own misbehaviour at Cannes, where he had drunkenly rejected the cuff-links offered to him as best actor in This Sporting Life, and scarpered clutching the prize for Best Animation. Pinelli, who had helped Fellini recycle recent celeb scandals and antics into the stuff of La dolce vita, was obviously attempting a slight reprise here.

Harris broods and Soraya scowls at the opera, in luxury hotels, and on the beach, where a telephone is produced by a waiter so Harris can brood long-distance. The telephone is neither grey nor beige. It's that colour known only to the swinging era, greige. This is a greige telephone movie.

A further party in Venice, masked and dissolute, cements the Eva connection, and there's little more to say: the jet-set lifestyle of royalty and feted artists has rarely looked more unamusing. A pervasive emptiness gusts through the opulent scenery and actors, rattling the Bulgari jewelry.

THREE FACES WEST

Soraya, who has thus far exercised her versatility by failing to act in Persian, Italian, German and English, now attempts the role of high-powered businesswoman in a minor comedy by minor comedy director Franco Indovina. The film scores points immediately by opening like a parody of the previous two segments, an obscene parade of poshlust consumables, a grotesque fashion show, a collage of women's magazine imagery and actual women's magazines. Models parade for Soraya's idle pleasure, sweltering in the Roman heat in their fur coats, fur hats, fur trousers. Every garment you can carve out of an animal is marched across the lawn of the real estate tycoon's villa.

Trays of sparkling cocktails, bowls of fruit, and a telephone float about the pool as a radio-controlled yacht weaves among them. "Where's the cheeseboard?" I cried. Indovina, apparently a little deaf, cuts to a chessboard.

Enter Alberto Sordi, another actual performer hired to prop up our screen goddess. Sordi plays a paunchy Latin lover for hire, a high-class gigolo destined to be defeated by Soraya's exotic froideur, or something. Out of pity, she finally allows him to pose with her for a swarm of paparazzi. For the first time, the film has approached a tenuous relationship with some kind of actual content, however frivolous, but disaster is averted.

Watching I tre volti is an odd experience, if it can be said to be an experience at all. Has anything actually happened between opening and closing titles? Not really. However, in the course of making the film, Soraya - whose only other screen credit would be a small part in Hammer Film's She, where she's upstaged by Ursula Andress, upstaged by Bernard Cribbins, upstaged by the set walls - fell in love with the least of her three maestros, and stayed with him until his early death in a plane crash. So something came out of this dizzying emptiness. Some happiness was, perhaps, snatched. A human being who could not communicate anything through a cinema screen, communicated something face to face.

***

Thanks to David Wingrove and Roland Mann.

The Forgotten is a regular Thursday column by David Cairns, author of Shadowplay.