If you're like me, and let's assume you all are, you greet the discovery of a film called Tamango with the hope that it's some kind of anagrammatic sequel to Matango: Fungus of Terror. But it's not anything of the kind, it's a solemn drama about the slave trade. Idiot.

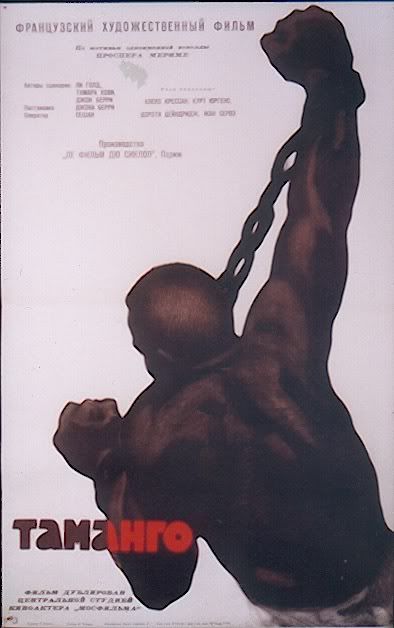

What distinguishes the film immediately is this subject matter, which had been pretty well ignored—and please do correct me if I'm wrong—by Hollywood, with the dubious exceptions of the various versions of Uncle Tom's Cabin, and those ante-bellum melodramas like Gone with the Wind which tend to relegate the issue of slavery to the background. And here's Tamango, a French production made in 1958, with an international cast including Curt Jurgens and Dorothy Dandridge.

Behind the unusual subject is an unusual filmmaker, John Berry, a blacklistee with an interesting slew of Hollywood productions behind him (He Ran All the Way is a good noir, and Casbah, the musical remake of Pepe le Moko, is better than you might think) who essayed a peripatetic career after directing the short documentary The Hollywood Ten and being prevented from working in America himself.

So it's not too surprising that Berry's script, adapted from a Prosper Mérimée short story, focuses on the question of defiance versus capitulation in the face of tyranny: Berry's life itself embodied this struggle, and he had just lived through a period where his friends had to make this choice themselves.

The slave ship Esperanza is sailing from Guinea to Cuba with a cargo of men and women purchased from an African chief (the movie is surprisingly frank about the collaboration of Africans in the slave trade). On board is the Dutch captain, Reinker (Jurgens), his mistress Aiché (Dorothy Dandridge, the only American star attached), the broken-down ship's doctor (Jean Servais, who had recently made a comeback working for another blacklistee, Jules Dassin, in Rififi), the rest of the crew, and a human cargo including several warriors and one natural leader, Tamango (Alex Cressan, a French athlete giving a strong performance in his only movie role).

At first, the film seems troublingly worthy and slow, concerned with laying out its message in the crudest terms, and unable to quite justify its humorless approach with genuine seriousness and depth: in a story where the lines between good and evil are so clear, there's a struggle to make the characters rounded. The Europeans are, by the nature of the story, unlikely to arouse sympathy, and even Servais's character, probably conceived as a more liberal humanist voice, with alcoholism as a humanizing flaw, seems to lose the interest of the filmmakers and finally seems not much less venal than the other whites. The slaves are naturally sympathetic, but the filmmakers have trouble bringing them to life as living characters, partly because of the cultural divide, and perhaps partly because the actors are dubbed from French to English, which does create a barrier between audience and performer. At least it avoids any "noble savage" crap. Dorothy Dandridge has the best role as a woman who has sided with her oppressors, placing her in a central, conflicted position.

But as the drama unfolds, with Tamango and his friends launching a series of attempts at mutiny, genuine suspense is generated—the Africans kill a crewman during a storm and must hide the corpse, and the skills of the tribal people is pitted against that of the supposedly civilized. Simultaneously, the tortured relationship between Jurgens and Dandridge generates actual emotional complexity. It also generates an inter-racial kiss, something you don't expect to see in a 1958 movie. While an American film, had it dared to tackle such a moment, might have celebrated the coming together of people of different color, the kiss here is between a slave-owner and a woman who occupies an uncertain position as lover and property. It's appropriately queasy, and Jurgens does a fine job of creating a sense of a rotten individual who still has occasional pangs of nobler emotions. They bother him, slightly.

(In fact, it seems the film was not released in America or the French colonies, due to the inter-racial sex plotline.)

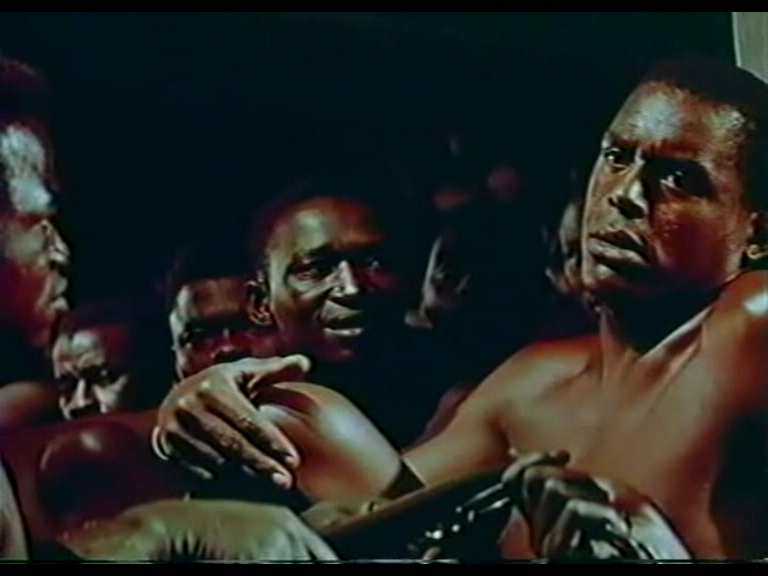

It's very hard to judge the visual aspects of the film, since the copy I obtained was both pan-and-scanned and prone to strange fluctuations of color. Berry may not have been a stylist as powerful as Losey or Dassin, but he gets some good value out of tracking through the ship's hold where the men are kept chained, and it would be nice to be able to appraise his work with more accuracy. Predating the epic TV mini-series Roots by nineteen years, and Spielberg's Amistad by thirty-nine, it's a work of considerable historic interest, rising to serious dramatic power as it builds to a near-apocalyptic conclusion, where Berry lets loose the anger and frustration he obviously felt at political injustice and persecution.

What's truly radical here isn't even necessarily the frontal approach to the story of the slave trade, it's that here's a story where the white Europeans are the bad guys and the Africans are the heroes, something one might assume to have been unthinkable at that time.

Maybe the film's intentions are better than its execution in some respects, but it's still pretty powerful, and a decent widescreen copy would almost certainly reveal more artistry than the fuzzy, cropped and oversaturated VHS can suggest. A film that was before its time might yet find its moment, if we can be allowed to see the thing.

***

The Forgotten is a regular Thursday column by David Cairns, author of Shadowplay.