Because of the abundandt entertainment value of so many of his films—and, among a few other things, the fact that he deigned to perform in a film for Steven Spielberg—there's a tendency among some cinephiles to perceive Francois Truffaut as something of an intellectual lightweight, particularly as compared to New Wave peers such as Jean-Luc Godard, Jacques Rivette, and Eric Rohmer. There's also the apprehension that in terms of themes, Truffaut was far more interested in the workings of the heart than of the head. And, seen from a particular perspective, his 1970 film The Wild Child (L'enfant sauvage), based on a true case in late 18th/early 19th-century France, would appear to be a cockle-warming tale of one devoted doctor's work to deliver a feral youngster into the bosom of human society. After all, does not the film begin with a dedication to Jean-Pierre Leaud, Truffaut's own "wild child," the untamed adolescent actor Truffaut transformed into an international icon?

Because of the abundandt entertainment value of so many of his films—and, among a few other things, the fact that he deigned to perform in a film for Steven Spielberg—there's a tendency among some cinephiles to perceive Francois Truffaut as something of an intellectual lightweight, particularly as compared to New Wave peers such as Jean-Luc Godard, Jacques Rivette, and Eric Rohmer. There's also the apprehension that in terms of themes, Truffaut was far more interested in the workings of the heart than of the head. And, seen from a particular perspective, his 1970 film The Wild Child (L'enfant sauvage), based on a true case in late 18th/early 19th-century France, would appear to be a cockle-warming tale of one devoted doctor's work to deliver a feral youngster into the bosom of human society. After all, does not the film begin with a dedication to Jean-Pierre Leaud, Truffaut's own "wild child," the untamed adolescent actor Truffaut transformed into an international icon?

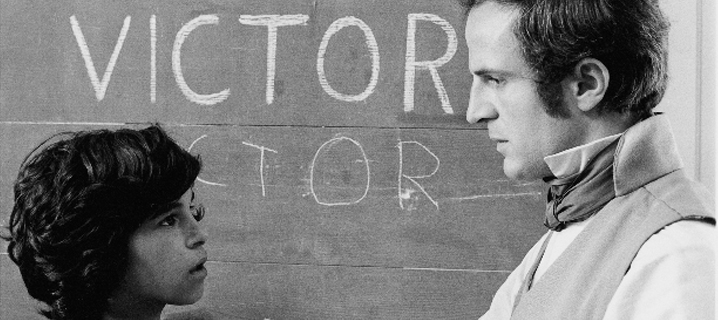

And certainly, the natural charisma of Jean-Pierre Cargol, who plays Victor, encourages an empathetic perspective. The initially filthy forest fellow—all matted hair and scraped limbs when, at ten or so years of age, he is captured in the wild and delivered to the care of deaf-and-dumb expert Dr. Jean Itard (played by Truffaut himself)—exhibits real wide-eyed charm as he sticks his head out of a hansom cab (rather like a dog at an open car window), grinning as the wind whips through his hair, or when he ponders the light and heat of a candle.

Still. This is not a film that works to work on you. Truffaut's means are deliberately austere. His framing is often silent-movie style; the viewers frequently see the action from a very conventionally constructed fourth. The sparse music is relatively understated Vivaldi (the use of such music is possibly the most overtly influential aspect of the film; c.f. Wes Anderson's Rushmore, and go backwards from there). The picture is also one of Truffaut's shorter features, clocking in just a few ticks over 80 minutes. The Wild Child, unlike quite a few other "based on a true story" films, doesn't show what became of its subject after the period portrayed in the film.

Still. This is not a film that works to work on you. Truffaut's means are deliberately austere. His framing is often silent-movie style; the viewers frequently see the action from a very conventionally constructed fourth. The sparse music is relatively understated Vivaldi (the use of such music is possibly the most overtly influential aspect of the film; c.f. Wes Anderson's Rushmore, and go backwards from there). The picture is also one of Truffaut's shorter features, clocking in just a few ticks over 80 minutes. The Wild Child, unlike quite a few other "based on a true story" films, doesn't show what became of its subject after the period portrayed in the film.

That's because by the end of the film its point is absolutely made, almost as in a mathematical proof. Much of Itard's effort is spent trying to teach the boy to speak, to recognize objects by name, to learn the alphabet...to learn his own name. In this, Itard is unfailingly kind and largely patient, but also frustrated. But he is also concerened with socializing Victor, giving him a sense of self, and, finally, making him a moral creature. He needs for Victor to understand the difference between right and wrong. He initiates a system of rewards and punishments. Does Victor merely accept this system as something rote, or can he understand what he'll be rewarded or punished for?

Itard never expresses a philosophy of morality. He doesn't evoke Rousseau, who was buried in the Pantheon a few years before the action of the film begins. More importantly, he never evokes God, either. What he does—and it's terribly painful for him—is subject Victor to an injustice.

Victor's indignant reaction is the climax of the film, and a beautiful, elegant, and, yes, moving refutation of the notion that without theism, moral chaos is inevitable. It was never discussed as such at the time of its initial release, but in today's God wars, Truffaut's film is a potent parable for non-believers.

***

The Wild Child plays at New York's Film Forum through Nov. 13