This is an excerpt from Nick Pinkerton’s Goodbye, Dragon Inn, available to order from Fireflies Press.

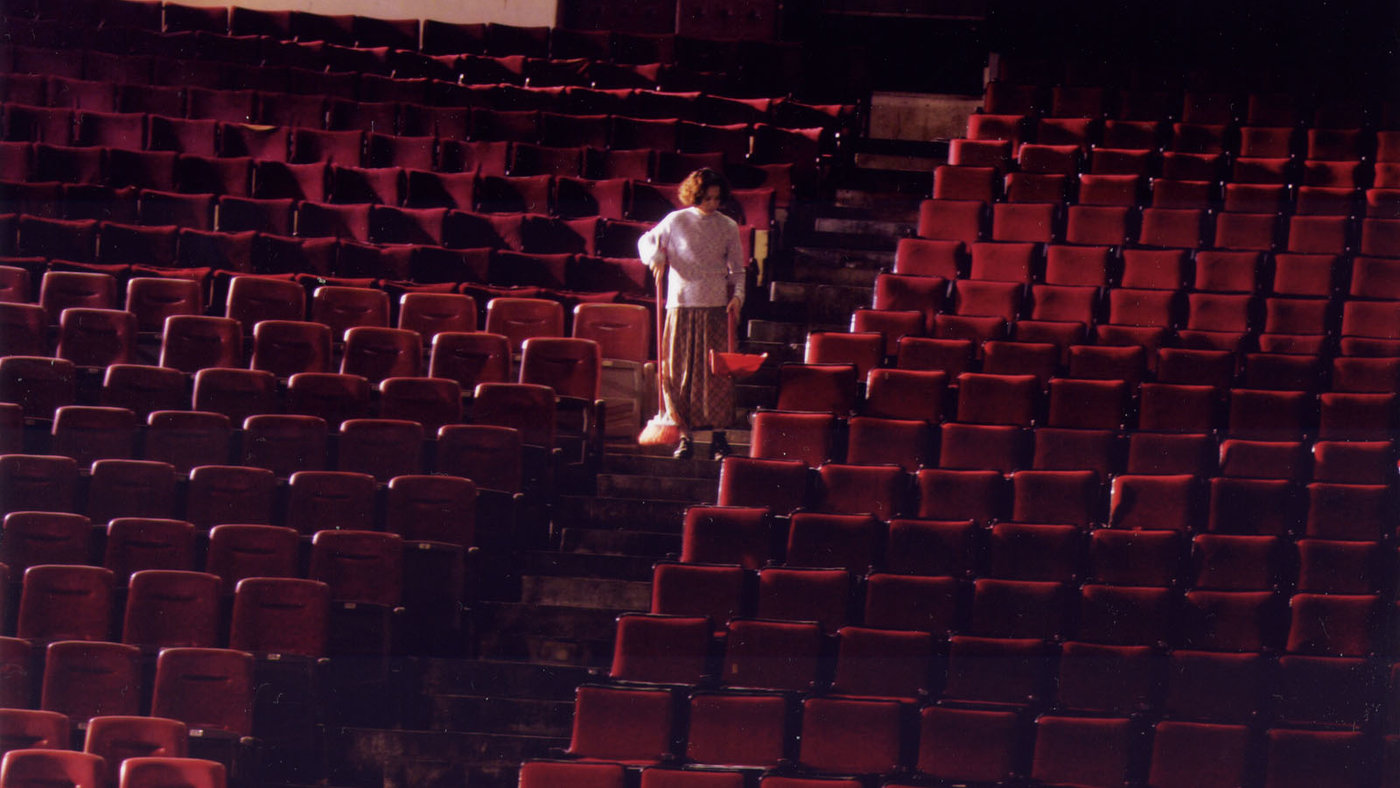

The fanfare that opens Goodbye, Dragon Inn is followed by a comedown crash. The prologue gives us a vision of the Fu-Ho in its heyday, but immediately afterwards we encounter a Fu-Ho that’s anything but Grand. It’s just another underpopulated declining urban theatre on the eve of a ‘Temporary Closing’, which one suspects management has optimistically identified as such in order to soften the blow of their establishment’s inevitable quiet passing, leaving behind no next of kin when it goes. A torrential rain – a regular presence in Tsai’s wringing-wet filmography – is lapping at the lobby, and there is a sense that the entire operation might soon be underwater. Après le cinéma, le déluge.

This temporal leap takes us from a full theatre to a nearly empty one, from the booming popular cinema of Greater China that Tsai knew in his mid-sixties youth to that same popular cinema at the turn of the millennium, now antique, an etiolated remnant of its former self. Goodbye, Dragon Inn has sometimes been taken as Tsai’s sweeping, definitive statement on the state of cinematic art and its waning appeal, but the narrowness of the movie’s focus – one film, one cinema, two screenings – ill suits it to such a purpose. In actuality, Taiwanese audiences were still very much turning out to see movies in the early aughts: Peter Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King, to take one example, grossed NT$400M (roughly US$11.5M) in the year of Tsai’s film. Rather, Tsai is concerned with a specific type of cinema, both film (a particularly lyrical example of the heroic wuxia of the sixties, this one made in Taiwan) and physical space (the large, single-screen urban theatre).

The audience for Dragon Inn has changed since childhood, and so have the preoccupations of the now-adult observer. The nagging presence of sex separates the ageing Fu-Ho from the idealised cinema of a child’s memory, a popular cinema seen at its prelapsarian pinnacle. The movie is only an afterthought for most of the contemporary theatregoers, pushed and pulled about by carnal need. The stowaway-peopled interior of the Fu-Ho, where boys float and brush past each other like buoys, is a ramble of aimless corridors and storage rooms crowded by sagging, soggy cardboard. All of the walls seem to be the same shade of soiled aquamarine, each corner stained with dark tendrils of water damage, and everything contributes to the overall impression of being in the hull of some great vessel off on an underbooked farewell cruise, where the muted, echoing soundtrack of Dragon Inn approximates the moans of a pressurised belowdecks. A few remain in a hall designed to house thousands, and the empty space takes on an eerily palpable presence of its own. When one of the Fu-Ho’s occupants does finally open his mouth, it’s to enquire, ‘Did you know this theatre is haunted?’

The Fu-Ho had already played a part for Tsai in What Time Is It There?, which likewise explored the cinema’s role as a cruising spot – very much an evocation of the theatre’s real-life function. Wrote Tsai: ‘After declining popularity but before closing down [the Fu-Ho] was said to have a few people of the gay community patronize the place... I’m very moved by this. Though it has declined and lost its glitter and you have forgotten about the theater, it still continues a long journey and still welcomes the outsiders of society.’

In that film, Hsiao-kang’s visit to the Fu-Ho is introduced by a shot very nearly identical to that which introduces us to Chen’s character in Goodbye, Dragon Inn: the camera is in a hallway facing out towards the cinema’s lobby, the women’s bathroom on the right of the frame. (A found rather than constructed set, the Fu-Ho suggests or imposes certain compositional approaches – a location is not only a “character” in a film, but a collaborator of sorts.) Like Goodbye, Dragon Inn, What Time Is It There? focuses on two people and their separate, isolate timelines. In the case of the earlier film, however, there is a moment of crucial overlap. Lee, playing a street vendor selling timepieces at the skywalk at the Taipei Train Station, meets a woman, played by Chen, who is about to depart for Paris, and is in the market for a wristwatch that will keep the time at home and abroad. Purchase made, she leaves, and he stays on; the film tracks their respective, largely lonesome urban perambulations. She makes her way through a foreign city where she knows no one and doesn’t speak the language. He becomes a foreigner at home by taking a plunge into Francophilia, developing an interest in French wine and cinema, and a mania for changing clocks across Taipei six hours back, to Paris time.

The Fu-Ho’s big scene in What Time Is It There? comes when Hsiao-kang snatches a wall clock from the cinema’s hallway and sits down to watch a film alone with his new acquisition. His privacy is interrupted by the appearance of a husky, bespectacled young man who has been trailing him since an earlier encounter at a shop, and plonks into the seat next to him. When Hsiao-kang moves over, the young man makes off with the clock, to lure Hsiao-kang, in pursuit, to the upstairs men’s bathroom. The bathroom at first appears empty, but then one of the stalls pops open to reveal the young man with his pants down and the clock face positioned over his crotch, its hands suggestively twitching, as though manipulated by a throbbing hard-on.

The set of cagey strategies that make up this vignette – approach, withdrawal; pursuit, recoil; thrust, parry – are further elaborated and played out in touch-and-go variants throughout Goodbye, Dragon Inn. Once again, the Fu-Ho Grand’s men’s bathroom appears as a space crackling with sexual potential. The strategic choosing of seats by those wandering the nearly empty cinema hall, where elected proximity functions as an announcement of erotic interest, plays out in an even more overt context in the toilets. A fixed-camera shot, running about three minutes in length, opens on the Japanese tourist taking up a urinal next to a lone man despite the abundance of free space: a long row of unoccupied urinals recedes into the distance. The pair are then joined by a third, who sidles up beside the Japanese tourist, hemming him in on both sides. The room is silent save the sound of running water, but the tense air of expectation is broken, briefly, when a stall door opens behind them, revealing the presence of a heretofore unnoticed fourth party, who steps out, leaving the door ajar, and goes to wash his hands. As he does, a hand appears and pulls shut the stall door, announcing still another occupant of the room and the likely fact that at least someone in this theatre of choosy comparison shoppers has managed to successfully pop their cookies. Finally, a sixth man enters the bathroom, walks over to the urinals and reaches between the Japanese tourist and one of his neighbours… to retrieve a pack of cigarettes left on the sill in front of them. Another breach of etiquette, in a scene already bristling with them, its minutely calibrated sight gags suggesting a Jacques Tati who has turned his attention to a comedy of cruising manners.

***

Tsai’s film was not alone around this time in exploring the function of the cinema as a cruising spot – Wong Kar-wai includes a boozy, woozy blowjob in a Buenos Aires cinema in his Happy Together (1997) and the second film by Jacques Nolot, the self-explanatorily titled Porn Theatre, premiered in Cannes a year before the release of Goodbye, Dragon Inn – carrying on a legacy of films dealing with the peculiar protocol at play in adult cinemas that runs through Marie-Claude Treilhou’s Simone Barbes or Virtue (1980) and Bette Gordon’s Variety (1983). Both Wong and Nolot stage their scenes in theatres heard to be playing porno movies, the onscreen action being kept out of view. Such venues are increasingly scarce in a post-home video, post-internet era, where one can easily get one’s rocks off in the privacy of one’s own office; these spaces continue to operate today, on the odd occasions that they do, by functioning as an arena largely dedicated to same-sex male cruising and, even in this, catering to an ageing, shrinking clientele. New York City is presently home to only two such cinemas, the Kings Highway Cinema in Gravesend and the Fair in East Elmhurst, Queens, with a third, Manhattan’s underground Bijou at 82 East 4th Street, having recently closed its doors.

The Fu-Ho isn’t explicitly catering to the raincoat crowd; insofar as we can tell, it is a “straight” commercial theatre, seen on the evening of a revival run – an unusual event judging from the visible posters, which include several for the Pang brothers’ 2002 The Eye (a Hong Kong-Singapore co-production and, fittingly, another ghost story). By the early aughts there was reportedly only one cinema left in Taipei still showing “blue movies”, presumably the Baixue grindhouse in Ximending, which was said to mix in Category III films from Hong Kong with straight fare, and was a popular cruising destination prior to its closure in 2012. (This sort of mixed-use programming was not unknown in the States; I used to frequent the three-screen Foxchase 3 in Alexandria, Virginia, which since the mid-seventies had been screening a combination of second-run arthouse movies and hardcore, and was demolished in 2005.)

Pornography has been a part of the private and public life of Taiwan since at least the sixties. Despite the KMT government’s stringent regulation of porn – one of the targets of the party’s Culture Purifying Movement – the first Danish, Dutch and Swedish smut found its way into Taipei cinemas at much the same time that it was taking the rest of the world by storm, followed in short order by a landfall of American adult films. The Yanks then dominated the Taiwanese market, abetted by a twelve-year ban on Japanese movies instated by the KMT, begun in 1972 in response to Japan’s severing diplomatic relations with the ROC and establishing them with the PRC (the Japanese-ness of the cruising tourist in Tsai’s film has a particular weight, given the fraught history between the two countries).

In porn, as in many things, little Taiwan found itself sandwiched between the influence of larger powers. By the eighties, Japanese AV (JAV), distinguished by its mosaicked genitalia and ingenious perversity, had gained a foothold through home video and broadcast on illegal cable television. In 1993, the KMT passed the Cable Radio and Television Law which officially legalised the use and broadcast of pornography in Taiwan. Still today, however, most Taiwanese talent gravitates to work in the bustling JAV industry – making the events of Tsai’s next film, The Wayward Cloud (2005), in which Hsiao-kang becomes a porn performer, slightly unusual, if not impossible.

Goodbye, Dragon Inn is relatively chaste, at least as films concerned with cruising go, while The Wayward Cloud is quite explicit in its scenes of mechanistic rutting (at the time of writing, the film can be viewed in total at the porn-hosting site xvideos.com). A despairing facial money shot introduces one of The Wayward Cloud’s marvellous musical sequences, a barrelhouse blues number by Grace Chang mouthed by actress Yang Kuei-mei – but the release comes through the performance, not the final joyless, dutiful delivery of a gout of spooge.

Goodbye, Dragon Inn is a long, frottage-heavy tease without release, and as such makes an interesting counterpoint to Nolot’s Porn Theatre, a film largely given over to matter-of-factly presenting the conventions of negotiating a mano a mano hook-up or group grope in the dark of a cinema. It is worth noting that the multi-hyphenate Nolot is the former lover of Roland Barthes, whose ‘Leaving the Movie Theater’, published in 1975 in the journal Communications, is one of the essential texts on the erotics of the cinema – and for Barthes, like the Tsai of Goodbye, Dragon Inn, ‘cinema’ connotes not only a medium, but a place: ‘Whenever I hear the word cinema,’ writes Barthes, ‘I can’t help thinking hall, rather than film.’ He goes on:

What does the ‘darkness’ of the cinema mean? ... Not only is the dark the very substance of reverie (in the pre-hypnoid meaning of the term); it is also the ‘color’ of a diffused eroticism; by its human condensation, by its absence of worldliness (contrary to the cultural appearance that has to be put in at any ‘legitimate theater’), by the relaxation of postures (how many members of the cinema audience slide down into their seats as if into a bed, coats or feet thrown over the row in front!), the movie house (ordinary model) is a site of availability (even more than cruising), the inoccupation of bodies, which best defines modern eroticism – not that of advertising or striptease, but that of the big city. It is in this urban dark that the body’s freedom is generated; this invisible work of possible affects emerges from a veritable cinematographic cocoon; the movie spectator could easily appropriate the silkworm’s motto: Inclusum labor illustrat; it is because I am enclosed that I work and glow with all my desire.

The history of cruising at the cinema, it can be reasonably supposed, is as old as the medium itself. The hysterical reactions of matriarch Amanda Wingfield to son Tom’s nightly excursions to the movies in Tennessee Williams’s 1944 The Glass Menagerie make quite a bit more sense when you consider that the memory play is the work of a gay man who’d spent his miserable mid-twenties working at the St. Louis factory of the International Shoe Company and concealing his furtive pleasures from the overbearing mother with whom he cohabited. (As in Williams’s play, Tsai and Lee’s earlier Hsiao-kang films are concerned with the practical exigencies of hiding one’s sex life from the family with whom one shares a living space, a concealment which in The River flows towards a catastrophic confluence.)

A peerless account of the socio-sexual function of cinema buildings can be found in Samuel R. Delany’s 1999 diptych of essays Times Square Red, Times Square Blue, which offers a first-hand autobiographical account of the author’s regular visits to certain New York City movie theatres for same-sex encounters. The memoir section of the book covers a period of more than thirty years, beginning in the mid-sixties and ending with the Giuliani era “clean-up” achieved through the reworking of zoning laws, the crackdown vigilance of the Public Morals Squad and the swing of the wrecking ball, which vanished once thumping strips like the Deuce, the formerly cinema-clotted district on 42nd Street between 7th and 8th Avenues. Delany brings us inside a number of cinemas: the Eros I, Capri, and Venus, a trio of mini-theatres lining 45th Street to 8th Avenue; the Adonis on 51st Street, opened in 1921 as the Tivoli; and the Variety Photoplays on Third Avenue between 13th and 14th Streets, immortalised in Scorsese’s Taxi Driver (1976) and Variety. All are now gone. The Eros has become the Playwright Celtic Pub. The Adonis was demolished in 1995, replaced three years later by a 26-storey apartment building. The Variety Photoplays is now a glass box condominium; the theatre closed in 2004 and was torn down the following year.

What Delany is eulogising is not only these physical theatres or the films they showed – though he has much to say on both subjects – but instead the entire culture of the casual public encounter, in this case a sexual one, that their existence facilitated. This, too, is part of what Tsai’s movie bids goodbye to – the beacon brightness of the neighbourhood theatres that welcomed flocks, as well as their touching final acts, in which they became smouldering havens for a few stragglers looking for a casual caress.

***

In his analysis of the ‘metacinematic cruising’ in Tsai’s film, scholar Nicholas de Villiers notes how the positioning of the Japanese tourist’s search for sex against the backdrop of Hu’s wuxia classic proposes a counterpoint between two kinds of random encounters. Tsai’s films, per de Villiers, place the issue of desire at the forefront and are distinctly modern and urban in character, revolving around the sort of chance encounters that a tightly packed city encourages – take for example The River, the events of which are set in motion when Chen catches sight of Lee as they pass one another on escalators headed in opposite directions. Hu’s film, by contrast, represents the landscape of rural inns and countryside highways of the ‘classical novel or wuxia pian cinematic narrative’, in which homoeroticism, if perhaps present on some level, doesn’t find overt expression.

The wuxia – the word is commonly translated as ‘martial heroes’, and sometimes as synonymous with ‘martial arts’ – is both ancient and relatively new, like so much in the popular culture of Greater China. Wuxia stories centre on heroic xia warriors, and the scholar Sam Ho draws out an effective definition of the genre in its very name:

The Chinese word wu is written by combining two other characters, zhi and ge, meaning ‘stop’ and ‘fight’, respectively. In other words, the term is an oxymoron, suggesting that it takes fighting to put an end to fighting, a paradox that is central to the appeal of the wuxia form. The term xia, however, has nothing at all in common with the English ‘arts’. It can be loosely translated as ‘chivalrous hero’, although that meaning incorporates connotations that have accumulated over time.

In literary form, wuxia can be dated back to the ninth century, in the later Tang Dynasty. The Ming period produced much-cited classics – Water Margin and The Romance of Three Kingdoms – but it wasn’t until the early years of the ROC that the modern wuxia novel appeared, published in serial form in newspapers that sought to secure the services of popular writers in their circulation wars. Films followed: Tianyi, a Shanghai studio operated by the Shaw brothers, later of Hong Kong, made one of the first known wuxia films, Swordswoman Li Feifei, in 1925. The production of wuxia in China would eventually be barred by the relentlessly modernising KMT, who deemed the genre retrograde and encouraging of superstition, but the movies never wholly disappeared between then and their breakout moment in the mid-sixties, their production having largely decamped to wide open Hong Kong and other sites.

As a “national” genre, the wuxia has most often been likened to the American western and the Japanese chambara, or samurai film. Like the western and samurai hero, the wuxia hero is guided by a personal code, though unlike the samurai, they typically stand outside of, and are often placed in direct conflict with, the aristocratic power structure. Pertinent to Tsai’s cinema – and here is the connection that de Villiers draws out – the wuxia hero is a wayfaring stranger, travelling the countryside of an ancient China that as often as not is being terrorised by its leaders, righting wrongs through martial mastery. Tsai, too, focuses on wanderers through hostile environments, though his chosen landscape is the depredated modern city terrorised, in a less direct and heavy-handed manner, by its leaders – not scheming eunuchs, but rather an eternally rebuilding local government and the larger forces of global capital, from the mandates of which no locality can be sovereign. This ongoing process of head-first, ravenous change, and in particular the continual destruction and reshaping of the city that goes on with little regard to servicing the needs of any but its richest residents, is felt throughout Tsai’s cinema. Tsai’s 1991 telefilm Give Me a Home and his 2006 I Don’t Want to Sleep Alone, for example, portray the difficulties of construction workers and labourers who toil to alter the urban landscape while standing to benefit in no way from the changes.

His proclivity for dramatising urban peregrinations have led many to compare Tsai, particularly early in his career, to Antonioni, though Tsai is individuated by, if nothing else, his sense of humour, a characteristic Antonioni can’t be said to have had in overabundance. Tsai’s films are undeniably suffused with the pain of alone-in-the-crowd urbanity, and in this belong to a rich strain of Taiwanese filmmaking: not for nothing did Hou pick the title A City of Sadness. Time and again in Tsai’s films the metropolis is seen as a place that breeds isolation and loneliness. But if city life is a sickness, through holding forth the potential for contact it also contains the possibility of its own cure.

‘Antonioniesque’ is often used as a shorthand for any film dealing with alienated wandering and urban anomie, though the concept of the flâneur observer predates the beginning of the Italian’s career by a century or so, its legacy running through Baudelaire to the Walter Benjamin of The Arcades Project – which could be an alternate title for Rebels of the Neon God, with its time-capsule record of the video game parlours of Ximending, before the extensive public works that would transform the area into a bright, carnivalesque pedestrian district modelled after Tokyo’s Harajuku. For Baudelaire, writing in ‘The Painter of Modern Life’, the ambulatory gaze of the flâneur seeks ‘to extract from fashion whatever element it may contain of poetry within history, to distil the eternal from the transitory.’ While Tsai’s camera does something akin to this for Taipei, Paris, Kuala Lumpur in I Don’t Want to Sleep Alone and Bangkok in Days, his characters are usually obeying more protean, and often romantic/erotic drives.

In his The Flâneur: A Stroll Through the Paradoxes of Paris, the writer Edmund White connects the figure of the flâneur – ‘that aimless stroller who loses himself in the crowd, who has no destination and goes wherever caprice or curiosity directs his or her steps’ – to the act of cruising, proclaiming, ‘To be gay and cruise is perhaps an extension of the flâneur’s very essence, or at least its most successful application.’ Something in the French character seems to lend itself to the cinematic depiction of the act of cruising; the last twenty years have not only given us Nolot’s Porn Theatre, but also Alain Guiraudie’s Stranger by the Lake (2013) and José Luis Guerín’s In the City of Sylvia (2007), which tracks the movement of a heterosexual male’s wandering eye through the streets of Strasbourg. (Wilson notes that while the English ‘cruise’ has a strictly gay connotation, the French draguer is also heterosexual.)

Baudelaire’s flâneur of the 1860s wandered a Paris unrecognisable from what it had been ten years previous, and to be rendered unrecognisable again ten years hence, a city in the midst of the seventeen-year process of Haussmannisation – the massive public works programme initiated by Emperor Napoléon III and spearheaded by his prefect of Seine, Georges-Eugène Haussmann, which turned the knotty, dark, cluttered medieval city into the metropolis of broad boulevards we know today. Today, in most every major city in the world, from Ximending to Times Square, a new sort of Haussmannisation is and has been underway, one of its models the process of redevelopment that Delany describes.

Delany’s project was born of years observing the changing face of the city around him, an awareness of which is one of the side effects of growing older. On his early forays into Times Square, he writes, ‘Like many young people, I’d assumed the world –the physical reality of stores, restaurant locations, apartment buildings, and movie theaters and the kinds of people who lived in this or that neighbourhood –was far more stable than it was.’ Kent Jones, in a not wholly dissimilar vein, comments on awakening from this illusion of continuity in cinema at the dawn of the twenty-first century, for ‘through the nineties, “The Movies” was a common reference point, as apparently solid as the Grand Canyon.’ It was the first glimmer of this impermanence of things, I believe, that I experienced in 1997 at the Tri-County 1-5.

With the passage of time, the transitory, mutable nature of a cityscape – or an art form – becomes more and more evident. If you stay in a city long enough, it becomes populated by the ghosts of storefronts past – the restaurants that are now Chase banks, the Dunkin’ Donuts that used to be a bar where you once puked in the bathroom sink, the storefronts and cinemas standing empty while neighbourhoods are made ghost towns by the prohibitively expensive demands of landlords. This consciousness of change was central to Antonioni and several of his Italian contemporaries, whose films captured the concrete fever of the Italian economic miracle – il boom – and it is essential, too, to Tsai.

‘Our cities are changing all the time,’ he has said. ‘It is as if we are living in a giant building site. I never avoid these places in my films. They remind us of what we are losing. They have an emotional appeal, as if they are characters themselves with their own stories to tell.’