Jeff Cashvan's original one-sheet for our December 11, 2014 screening of The Mystery of Chess Boxing at Nitehawk Cinema.

Movie-lovers!

Welcome back to The Deuce Notebook, a collaboration between MUBI's Notebook and The Deuce Film Series, our monthly event at Nitehawk Williamsburg that excavates the facts and fantasies of cinema's most infamous block in the world: 42nd Street between 7th and 8th Avenues. For each screening, my co-hosts and I pick a title that we think embodies the era of 24-hour grinding, and present the venue at which it premiered...

This month: yet another special guest, honorary Deuce-Jockey and bestselling writer Grady Hendrix. Co-founder of the New York Asian Film Festival, a seasoned movie curator and presenter, and novelist of many knock-out genre-benders like Horrorstör, The Final Girl Support Group, and We Sold Our Souls, Grady is one of the busiest guys in the biz.

Up next for Grady: his newest book These Fists Break Bricks: How Kung Fu Swept America and Changed the World, co-authored with last month’s guest Chris Poggiali, will be published this September… We’ll let you know when it’s out!!

Below, Grady's essay on one helluva double feature, Mad Monkey Kung Fu and The Mystery of Chess Boxing—two rough-and-tumbles that walloped the Deuce throughout the 1980s... Enjoy!

—The Deuce Jockeys

From The New York Times, July 2, 1981.

On June 27, 1981, Gerard Coury called home in a panic from the Conrail police offices in Grand Central Station. “Mom,” he pleaded. “Help me get out of here.”

On his way from Connecticut to a job interview in Washington, DC, the 26-year-old had changed trains in New York City where he’d been robbed of his luggage, his wallet, and the clothes on his back. All he had left were his pants. While his mother tried to arrange help, Coury waited in Grand Central Station. Sometime between 7:30pm and 11pm, he disappeared. The next time anyone saw him it was almost dawn and he was running naked down 8th Avenue and across 42nd Street, pursued by a group of 20 kids and “vagabonds” who laughed at him and threw bottles. “He was just bugged out,'' 13-year-old Tracy Richardson said, “and everybody started going wild on him. They had nothing better to do.”

Coury entered the subway and slipped under the turnstile but the mob chased him onto the IRT platform. Coury tried to escape by leaping onto the tracks. He hit the third rail and died instantly. He had no drugs or alcohol in his system and was originally classified as a “mentally disturbed individual” who’d committed suicide. When his family came forward the cause of death was changed to a “heart attack brought on by terror” then, finally, “electrocution.”

The story received major coverage in the New York Times for a few days, offering further confirmation that New York City was a hellhole and its heart was a meat grinder shaped like the Deuce. Everyone knew the stats. With 8,000 pedestrians wandering down the Deuce every hour, the street and its surrounding 10-block radius saw 464 felony arrests in the first 5 months of 1981 alone. That’s less than half of the 1,107 reported felonies in that same time period.

“This place is a jungle,” Jamie Owens, a guard at the Cine 42 said. He made that comment immediately after his fellow guard had been arrested for beating a patron so badly with his nightstick he split open his skull.

Marcus Boas painted the Mad Monkey Kung Fu poster and also handled the lettering. Distributor Larry Joachim had spotted his work at a convention and paid him $1,000 per poster. Legendary comic book artist Neal Adams painted the poster for The Mystery of Chess Boxing and, surprisingly, he often handled posters for a seemingly random assortment of New York distributors. Not only did he paint Jackie Chan’s Eagle’s Shadow for Serafim Karalexis, but he also did several posters for Howard Mahler Films.

1981 was the year kung fu movies in America and Hong Kong went their separate ways, with the Deuce’s reputation for extreme mayhem not only coloring this country’s perception of kung fu films but sowing the seeds of their eventual destruction. Nothing tracks the story better than the fate of two 1981 releases: Mad Monkey Kung Fu and Mystery of Chess Boxing. Both came out in Hong Kong in 1979, each one a different response to the kung fu comedy revolution that erupted in the wake of Jackie Chan and Yuen Wo-ping’s seismic 1978 two-fer, Snake in the Eagle’s Shadow (March 1978) and Drunken Master (October 1978).

Chan was a failed Bruce Lee clone at the beginning of 1978, when Seasonal Film’s boss and independent hitmaker Ng See-yuen asked to borrow him from Lo Wei, the director who held Chan’s contract (and who had directed Bruce Lee’s first kung fu movies before they fell out). Lo kicked his bad bet over to Ng who paired Chan with Yuen Wo-ping, a deeply accomplished action choreographer from a family of deeply accomplished action choreographers who was looking to make his directorial debut. Snake and Drunken deliver the same basic story: Chan plays a kung fu student too stupid (Snake) or too lazy (Drunken) to study. Under the tutelage of Beggar So, a hard-drinking, pipe-puffing old bum who happens to be a great kung fu master in disguise, he rises to the challenge of taking on Korean super-kicker, Hwang Jang-Lee, after some joint-cracking training sequences courtesy of So (played by Yuen’s insanely nimble 66-year-old father, Simon Yuen) and learning some exotic style of kung fu (Cat's Claw in Snake, Drunken Boxing in Drunken).

The movies blew the Hong Kong box office wide open, made Chan a star, kickstarted Yuen Wo-ping’s directorial career, and turned Simon Yuen’s Beggar So character into an icon he would play in another 15 movies before his death less than a year later in January 1979. They also ushered in a wave of kung fu comedies that zapped the traditional master/student dynamic with hard radiation, mutating the genre into a comedy powerhouse with raucous blood fizzing in its veins.

Released in November of 1979, The World of Drunken Master was just one of the many Drunken movies Simon Yuen churned out in the year following his iconic performance as Beggar So, this one from Joseph Kuo (Mystery of Chess Boxing) himself. Yuen’s role is mostly a cameo that let Kuo slap his picture on the posters, and it starred the cast from Mystery of Chess Boxing, Mark Long (Ghost Faced Killer), Jack Long (Mr. Chi the Chess Player), and Li Yi-Min (Ah Pao) playing young Beggar So.

Few relationships are as revered in Chinese culture as that of a master and his student. The student basically accepts his master as a father and pledges undying loyalty in exchange for getting (painfully) taught a unique set of butt-kicking skills. The relationship is best exemplified by the Wong Fei-hung films that ran from 1949 to 1970 in which Kwan Tak-hing played the real-life Chinese folk hero and avatar of Confucian virtue Wong Fei-hung in over 80 movies, many of them choreographed by Simon Yuen or Lau Cham. A stern teacher and extreme disciplinarian, Wong trains and punishes his students in equal measure, but he’s always right and they’re always wrong, and the tone is finger-wagging and tight-lipped.

This started to change in 1973. Shaw Brothers—the Death Star of the Hong Kong film industry, operating from its massive backlot, Movietown in Clearwater Bay—dominated the Asian screen thanks largely to their ultra-trendy angry young man action movies pioneered by director Chang Cheh, who, in 1967, famously said, “The whole world is immersed in violence. How can the cinema avoid it?” By the early ’70s , Chang’s movies were starting to lose their spark, especially after Bruce Lee’s raw, modern ragers came out in 1972 and 1973—giving Chinese audiences a sleek, sexy, proud, and powerful hero who didn’t have time for musty old traditions.

After Bruce Lee’s death in 1973, everyone wanted to find the next big thing and Lau Cham’s son, who had become a top action choreographer in his own right, had an idea. Lau Kar-leung had staged the brutal beatdowns in Chang Cheh’s movies, but now he suggested they ease up on the blood and guts and make more realistic kung fu movies featuring traditional folk heroes. Thus, the next big trend, Chang Cheh’s Shaolin Cycle: six movies released between 1973 and 1976 about the legendary cradle of Southern Chinese martial arts, Shaolin Temple. Mostly starring Alexander Fu Sheng as a Chinese folk hero, they often took a break in the middle to deliver an intense training sequence in which the hero levels up his kung fu under the stern gaze of his teacher and some wacky apparatus. Even though Heroes Two (January 1974), the first in the cycle, didn’t feature much training, Shaw paired it with a nine-minute documentary short called “Three Styles of Hung School’s Kung Fu,” made by Lau with the studio’s stars educating audiences on true Southern kung fu.

The Shaolin movies took off like a rocket and other directors climbed on board, with Joseph Kuo’s 18 Bronzemen (October 1976) becoming one of the biggest hits. Taiwan was a huge market for Hong Kong films and with its deep pool of talent and minimal restrictions on co-productions, filmmakers moved freely between the colony and Taiwan. Kuo had been a moderately successful Taiwanese writer-director whose cross-strait hit, The Swordsman of All Swordsmen (1968), got him hired by Shaw Brothers. His next big hit, however, was his own independently produced Sorrowful of a Ghost (1970) and he stayed independent for the rest of his career.

18 Bronzemen focuses on the 20 years of training undertaken by its main characters at Shaolin Temple, with a graduation exercise involving a series of trials against the ultra-powerful Shaolin Bronzemen. The movie became a much-imitated hit and received a rare 100-screen release in Japan. Lo Wei’s Shaolin Wooden Men (November 1976) was an even more baroque Shaolin training movie starring Jackie Chan and executed in a deadly serious vein; Lau Kar-leung then decided to show everyone how it was done with 36th Chamber of Shaolin (February 1978). Lau had parted ways with Chang Cheh after falling out with him on Marco Polo (December 1975), and became one of the most important kung fu directors of the day, pioneering a rigorously realistic, muscular, and slyly funny style of action moviemaking that tossed off genre-changing innovations like confetti at a ticker-tape parade. The 36th Chamber’s central training sequence was an hour-long genius-level, cinematic tone poem on how discipline, focus, commitment, and willpower can save you from yourself. The movie made his bald-headed brother, Gordon Liu, an international icon.

The 36th Chamber would be released by Mel Maron’s World Northal under the title Master Killer and became a big hit on the Deuce. They took out this trade ad to prime exhibitors for their release of the sequel Return to the 36th Chamber (August 1980) which hit American screens as Return of the Master Killer.

As the end of the ‘70s approached, Hong Kong’s increasingly cosmopolitan audiences started rejecting traditional kung fu flicks, and the cinematic master/student relationship finally got revamped by veterans of one of the most dysfunctional real-life master/student relationships in Chinese culture: Master Yu Jim Yuen and the Seven Little Fortunes. Master Yu ran the China Drama Academy, a tough Chinese Opera school whose most famous crop of kids included Sammo Hung, Jackie Chan, Yuen Biao, Yuen Wah, Corey Yuen Kwai, Yuen Tak, Yuen Tai, and Yuen Mo—who performed collectively as “The Seven Little Fortunes.” Brutally beaten, forced to stand in horse stance for hours at a time, often starved, all of them would have long careers in the Hong Kong film business and an ambivalent relationship with their teacher. While Jackie’s the best known of the bunch, it’s his “big brother” Sammo Hung who became Hong Kong’s most groundbreaking director and action choreographer after Lau Kar-leung. Three of his first four movies explored the master/student dynamic, delivering kung fu comedy alongside show-stopping training set-pieces. But it’s Jackie who broke big by rewriting the master/student relationship in 1978 with Snake in the Eagle’s Shadow and Drunken Master

Both Lau Kar-leung and Joseph Kuo responded to Jackie’s innovations with their 1979 films, Mad Monkey Kung Fu and Mystery of Chess Boxing, and they couldn’t have been more different. Lau Kar-leung was a product of the lavish Shaw Brothers studios and his movie featured gorgeous costumes, enormous sets, and top-tier talent like star Lo Lieh and action cinematographer Arthur Wong. Lau was a true martial artist who wanted to show off legitimate monkey-style kung fu, and he’d had a movie in the box office top ten for each of the previous four years, scoring two top ten movies in 1978.

In Mad Monkey he cast himself in a lead role for the first time, playing the teacher, Mr. Chan, a Chinese opera player who gets framed for raping Lo Lieh’s wife after humiliating Lo with his monkey-style kung fu. Lo Lieh, a criminal who controls the entire town, brutally smashes Lau’s hands then kicks him to the curb. Living on the streets, making ends meet by selling candy with his pet monkey, Lau falls afoul of local hoods running a protection racket. Street kid Little Monkey (played by Lau’s real-life student, Hsiao Hu), comes to his rescue and, after being humiliated and beaten by the street toughs, Lau agrees to take him as his student. They head into the mountains for a whole lot of training before coming back into town to kick enormous quantities of ass.

The action is impeccable and the storytelling is fast and furious. Intricate fights run up and down a two-story brothel set or spin around a soundstage marketplace complete with bridges and canals. Lau and Hsiao are extraordinarily gifted acrobats and the mountain training sequence, which begins with Hsiao digging up potatoes while wearing a BDSM dungeon’s worth of bondage weights on his fingers, ends with him essentially living 24/7 as a monkey. Despite a large quantity of comedy trombone on the soundtrack, the story continuously erupts with gruesome gore: head wounds that drip thick red Shaw Brothers blood and hideous hand mutilations. In the end, Monkey gets so carried away that he straight-up murders Lo Lieh and is about to beat his wife to death when his teacher, Lau Kar-leung, brings him to heel. As he says, “Monkey stays Monkey.”

Joseph Kuo’s previous hit had been 7 Grandmasters, another ultra-athletic kung fu cheapie shot mostly outdoors and during the day, with action choreography by one of Yuen Wo-ping’s brothers, Yuen Cheung-yan, and Seven Little Fortune, Corey Yuen Kwai. It was such a hit that some local ads, like this one for the Apache Drive-in down in Texas, advertised it as Return of the 7 Grandmasters.

Joseph Kuo’s Mystery of Chess Boxing, on the other hand, takes its cues far more directly from Jackie Chan’s Snake in Eagle’s Shadow. In Snake, Jackie plays a guy so dumb that the local kung fu school uses him as a walking punching bag until he makes friends with Beggar So and learns real kung fu. Unfortunately, Beggar So, the last master of Snake Fist, is being hunted by the master of Eagle Claw (Hwang Jang-Lee), and the movie ends with the seemingly invincible Hwang beating Beggar So to a pulp before Jackie shows up and bangs on his skull like a drum with his Cat’s Claw style.

Chess Boxing tells the almost identical tale of Ah Pao (Li Yi-min) a young dork who wants to learn kung fu at the Chang Sing School where he’s made a walking punching bag before befriending the cook (played by Simon Yuen) who shows him that kitchen work teaches the foundations of kung fu. Meanwhile, Ghost Faced Killer (Mark Long), master of the Five Elements Style, strolls around the Taiwanese countryside murdering all the other heads of the clans who conspired to have him killed. When Ah Pao gets thrown out of the Chang Sing School for possessing one of Ghost Faced Killer’s trademark medallions, he winds up learning true kung fu from Ghost Faced Killer’s last victim, Chi Siu-tien (Jack Long), a chess fanatic. Mr. Chi and Ah Pao team up in the final fight to take Ghost Faced Killer down with Chess Boxing, complete with groovy chessboard animations.

Sporting costumes that look like someone’s mom made them, shot almost entirely outdoors during the day because it’s cheaper that way, Mystery of Chess Boxing looks like it cost about $1.99. But the action is in overdrive right out of the gate and the fights sting. Kuo knows how to keep a story cooking, he’s got a knack for framing, and he’s excellent at delivering fun effects with nothing more than some nimble editing and clever camera tricks. His movie’s gimmick of teaching kung fu by teaching cooking and chess would reach its zenith in Hollywood with the Karate Kid movies, in which Pat Morita teaches Ralph Macchio karate by making him paint his fence and wax his car. When Seven Little Fortune member Corey Yuen came to America and saw The Karate Kid, he immediately phoned up Ng See-yuen and told him the Americans had ripped off Ng’s Drunken Master--only with worse action and no drinking. This would result in the two men delivering the No Retreat, No Surrender trilogy, which gave Jean-Claude Van Damme his first action role.

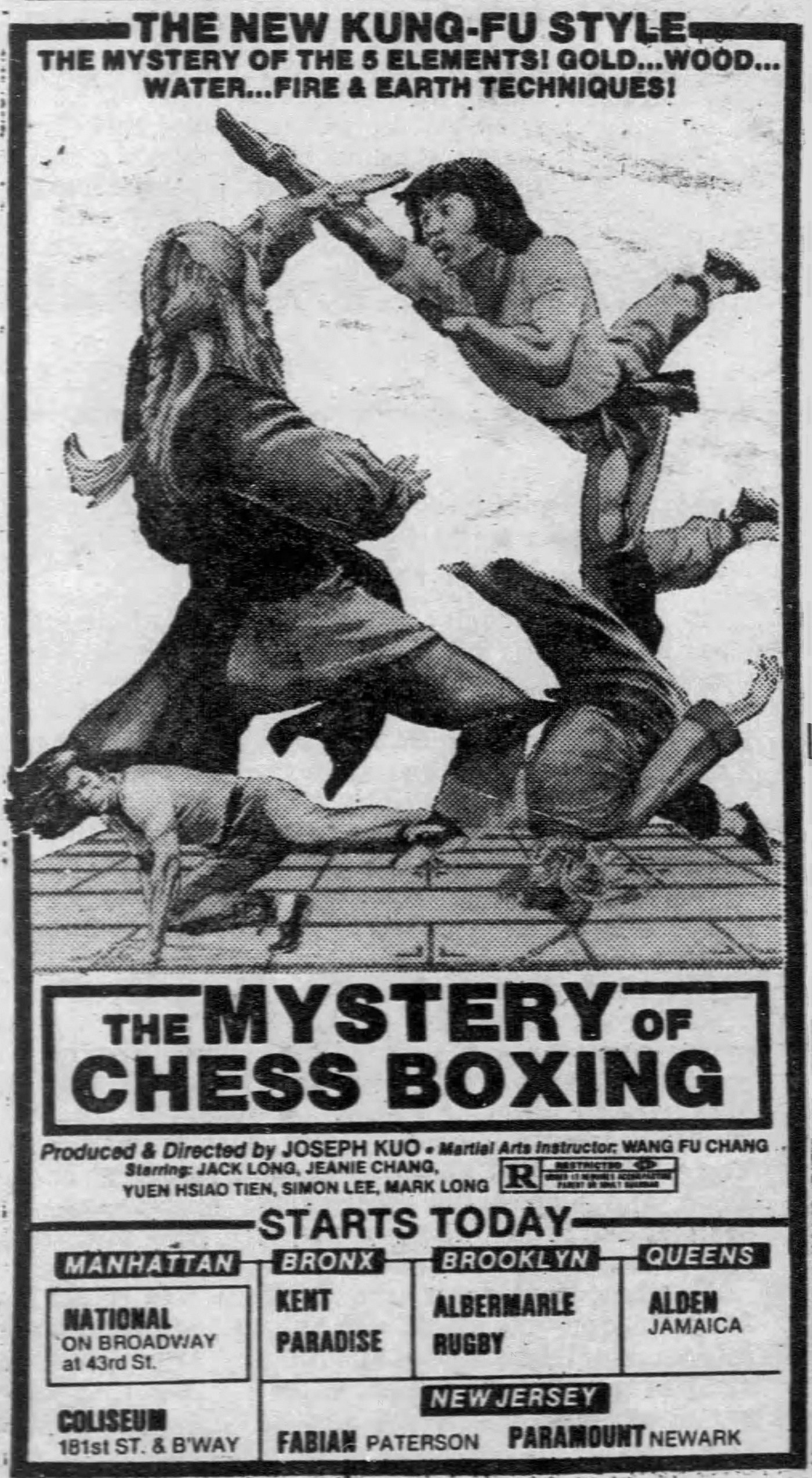

Newspaper ad announcing the New York premiere of The Mystery of Chess Boxing and leaving out the fact that although it opened at the National with premiere pricing on Christmas Day of 1981, it had actually played for a discount admission over at the Cine 42 two days earlier, alongside Joseph Kuo’s 7 Grandmasters.

Marvin Friedlander’s Marvin Films took on Chess Boxing in the States. Friedlander founded Marvin Films in 1966 to be a sub-distributor in NYC, Albany, and Buffalo for a variety of distributors including Cinema Shares, Film Ventures International, Russ Meyers, and New Line Cinema. Friedlander got in hot water alongside Terry Levene of Aquarius Pictures and many others (including some actors from the pictures) when he shipped two Sherpix porn films, School Girl and Kitty’s Pleasure Palace, across state lines. And thus the same idea occurred to Friedlander that occurred to lots of sub-distributors: kung fu movies were a way to make a buck without the headaches of hardcore.

Transcontinental picked up Mad Monkey Kung Fu but their ownership came via a more complicated and mysterious route. In the early ‘70s, Shaw Brothers delivered the first two major kung fu hits in America when their King Boxer (April 1972) became a blockbuster for Warner Bros. as Five Fingers of Death (March 1973), and Serafim Karalexis Americanized their 1971 picture, The Duel, and released it a few weeks later as Duel of the Iron Fist. After a handful of failures and embarrassments, however, Shaw decided it was no longer worthwhile to distribute their movies to the United States and it wasn’t until their sales agent, Wolf Cohen, persuaded them to sell an enormous package of their pictures to Mel Maron at World Northal in the late ‘70s that their movies began appearing regularly on American screens again. Mad Monkey Kung Fu, however, was not one of them. This Shaw picture wound up in the hands of Larry Joachim’s Transcontinental, a company that had shot to the top when its Green Hornet (October 1974), consisting entirely of re-edited footage from Bruce Lee’s 1966 TV show The Green Hornet, became a huge hit. Some people speculate that Transcontinental acquired three Shaw titles based on a 1973 deal with distributor Harry Shuster, but there’s no way to know for sure.

What is sure is that by 1981 American audiences couldn’t get enough of Bruce Lee with his ferocious, humorless style and, after his death, they demanded their kung fu be served with a big bowl of blood. While directors like Robert Clouse claimed that, “Unlike Oriental audiences, who seem to want as much blood and gore as you can give them, American audiences will tire of that rather quickly,” they certainly weren’t getting tired of it yet. When the more acrobatic, naturally puckish Chan tried to enter the American market with The Big Brawl (September 1980) it didn’t bomb, but the results were still disappointing. Warner Bros. wanted to find their next Enter the Dragon but so far, the only kung fu movie that did the numbers of Enter the Dragon was... Enter the Dragon, which they re-released to major success in the Spring of 1981. Even dead, Bruce Lee did big business, with Game of Death (June 1979) earning millions at the box office and its Bruce-free sequel, Tower of Death (aka Game of Death II, March 1981) did okay, too. (Incidentally, Tower was directed by Ng See-yuen.)

Jackie Chan was already a star to Chinese audiences in 1981, but he couldn’t seem to crack the American market. This photo was taken by Gregg Mancuso at the Bella Union in San Francisco’s Chinatown.

It wasn’t just Warner Bros., 21st Century Films also tried to sell Chan as another Bruce Lee with their May 1981 release of Snake Fist Fighter but, despite a trailer in which patrons enthused, “He’s definitely the greatest I’ve seen since Bruce Lee!,” audiences weren’t biting--most likely because the movie was a scam. Chan’s first movie, shot in 1971, was never completed but was eventually enhanced with additional footage and released in 1973 as The Cub Tiger of Kwantung. Footage of Simon Yuen got added in 1979 when it was released again, this time as Master With Cracked Fingers, which was retitled Snake Fist Fighter and rereleased by 21st Century in 1981 with new posters and an Adolph Caesar-narrated trailer.

21st Century’s poster for Snake Fist Fighter by an unknown artist. Argentinian artist Luis Dominguez painted most of their posters but this doesn’t look like his style.

One reason audiences may have rejected Chan’s more comic approach to kung fu was that, by 1981, kung fu movies seemed constantly connected to crime. Not only were most of the theaters that screened them in poorer neighborhoods, but newspapers overflowed with tales of moviehouse bloodshed. In February 1981, John “Spare Rib” Chan, the 23-year-old second-in-command of the Chinatown Ghost Shadows was murdered at NYC’s Music Palace Theatre while watching an unnamed kung fu flick. He had gone with his crew, but they couldn’t find seats together. Like a lot of gang members he wore a bulletproof vest which did him no good because his assailant shot him in the back of the head. On August 17, 1981, Minneapolis’s Ritz Theater, recently purchased by a new owner who announced plans to show exclusively Chinese films, was bombed 90 minutes after the last show ended, and “White Power” was spray-painted on its front. The New York Times’ stories about the death of Gerard Coury and beatings outside the Cine 42 hardly helped.

The Music Palace in the heart of Chinatown was the last surviving Chinese movie theater in North America when it shuttered in 2000. As the ‘80s progressed, theater owners on the Deuce would actually rent subtitled kung fu prints directly from the Music Palace and screen them illegally uptown for patrons. This photo is by Subway Cinema’s Goran Topalovic and Subway has a tribute to the Music Palace posted here.

Mystery of Chess Boxing and Mad Monkey Kung Fu, with their emphases on kung fu comedy, training sequences, and master/student relationships, worked perfectly in Hong Kong but were less suited for the American marketplace. Nevertheless, they turned out to be evergreen hits. Transcontinental opened Mad Monkey in September of 1981 at the Cine 42, paired with their Yasuaki Kurata movie Tiger’s Claw (aka Which is Stronger, Tiger or Karate?, 1976). It opened in 10 area theaters and would spend the ‘80s bouncing around Times Square, frequently paired with Police Academy 2.

Marvin Films released Mystery of Chess Boxing at the National on Christmas Day in 1981, although it had, in fact, premiered at the Cine 42 two days earlier on a double bill with Joseph Kuo’s 7 Grandmasters. It played until February of 1982 joined on the Cine 42’s other screen by Mad Monkey Kung Fu for a week starting on January 13, 1982, and then both movies got paired with The Boogens on separate screens the following week. Both movies played on and off the Deuce throughout the Spring before joining forces on the same Cine 42 triple-bill alongside Hot Dog Kung Fu (aka Writing Kung Fu, 1979) in June.

When Lenny Clark, owner of the Cine 42, leased the Rialto across the street, both movies started playing there and even became a triple feature the week of April 24, 1984, alongside Kung Fu Master Named Drunk Cat (1979)—another one of Simon Yuen’s Beggar So movies. When Clark leased the Harris, the two moved there. In fact, for the next five years, it’s difficult to find a year when Mad Monkey Kung Fu and Mystery of Chess Boxingdidn’t play the Deuce. Their final shows came in October of 1989, after they’d been MIA since 1986. Mad Monkey Kung Fu returned to the Cine 42, paired with Jean-Claude Van Damme’s Kickboxer, while Mystery of Chess Boxing saw its final screening that same month alongside Spike Lee’s Do The Right Thing.

The other thing that helped kill big screen kung fu at the end of the ‘80s were Johnnyray Gasca’s line of SB Video bootlegs. Shot on video from balconies, or duped directly from ¾” masters, Gasca’s SB Videos were the only way a lot of people saw Shaw, and they were sold in stores across the country. By the time World Northal closed its doors at the end of 1987, SB Video was doing peak sales with titles retailing at $69.95 a tape. “I made $97,000 from '87 to late '88, and about $40,000 in '89,” Gasca states. “The last title I put out was Stroke of Death aka Monkey Kung Fu. Then I went to California to try to get in the film business with Cannon.” When he saw SB Videos on the shelves in some LA video stores, he realized his tapes had arrived in Hollywood before he had.

1980-81 were benchmark years for the Hong Kong film industry. Jackie Chan, disappointed after the relative failure of The Big Brawl and his minor role in the hit Cannonball Run, headed home and started directing, starring in, and choreographing a string of movies that would transform him into one of the biggest action stars in the world. During those same years, Sammo Hung took the master/student movie as far as it could go with The Prodigal Son (December 1981), a posh wing chun picture starring Seven Little Fortunes classmate, Yuen Biao. A classy, big-budget hit, it saw Sammo nominated at the Hong Kong Film Awards for “Best Picture” and “Best Director” and winning “Best Action Choreographer” (beating out his “little brother” Jackie Chan). It was pretty much the last of the classic master/student movies, a luxurious farewell to a genre that had lasted throughout the ’70s.

In the States, martial arts movies were also done with the master/student relationship and elaborate training sequences; they’d ditched them to cling to retro tales of bloody revenge like the ones that had ushered in the early Chang Cheh movies before Bruce Lee supplanted them. 1981 saw Chuck Norris, America’s biggest martial arts star since Bruce Lee, open his Eye for an Eye (August 1981) and make $12 million at the box office. Norris didn’t do elaborate training sequences or acrobatics, he just punched people real hard. Most white martial artists didn’t have the skills to deliver intricate, acrobatic fights, and American filmmakers didn’t have the know-how to shoot them anyway, so, as homegrown martial arts stars became more and more prevalent in the States throughout the ’80s, they put the focus on gore and violence. It wasn’t until Jean-Claude Van Damme’s Kickboxer in 1989 that tournament movies and their longer bouts became popular.

The advertising manual for Chuck Norris’s Eye for an Eye that went out to theater owners.

The biggest kung fu story of 1981 in the States was the beginning of the end for kung fu movies: television. Throughout the ’70s, broadcast stations would happily air dubbed Japanese movies but avoided Chinese ones like the plague. However, World Northal’s Mel Maron thought the Shaw Brothers movies had an “almost bizarre entertainment value” and he realized that “a lot of kids were hungry to see those pictures, but they couldn’t because their parents felt uncomfortable letting them go to the downtown theaters.” So, if little Johnny and Suzy couldn’t go to the grindhouse, World Northal would bring the grindhouse to them.

Newspaper ad for KTTV’s repeat airing of The Chinatown Kid. Los Angeles’ KTTV conducted a running ratings rivalry with KTLA throughout the early Eighties.

In February of 1981, KCOP 13 in Los Angeles debuted the first film in World Northal’s “Black Belt Theater” package: Bruce Lee: His Last Days, His Last Nights. It earned killer ratings and in May “Drive-In Movie” on New York’s WNEW 5 debuted it too. That year Black Belt Theater package sold its 13 films to 40 stations across the country, including 25 of the top 30 markets. The day after Bruce Lee: His Last Days, His Last Nights aired on WNEW 5 Performance Advertising Systems debuted their package, “Tribute to Fist of Fury,” for a week-long series of broadcasts on KTLA during sweeps. Over the summer, “Drive-In Movie” would capture big ratings with airings of more “Black Belt Theater” films like Master Killer (aka 36th Chamber of Shaolin) and The Chinatown Kid (another Shaw Brothers Chang Cheh joint) which, to quote a trade ad they ran in Broadcast magazine, “aced a tennis match, beat out a Grand Prix, sliced up a golf tournament, outran a track meet, and clobbered two other movies.”

By December of that year, a third company, Telepictures, had jumped in the pool with a 16-title “Masters of Fury'' package, bragging that they’d struck new prints for them; shortly thereafter, Con Harstock announced he was preparing his own 11-title “Seven Commandments of Kung Fu” package. And at the end of the year, World Northal announced a 26-title “Black Belt Theater 2” package to debut in 1982.

One of the films that played in Performance Advertising Systems’ “Tribute to Fist of Fury” was Enter the Game of Death, a 1978 Bruce Le film which, as far as we can tell, didn’t even get released in Hong Kong until after it aired on American television.

With kung fu movies associated more and more with the idea of possibly getting murdered and robbed at the theater, and the availability of the movies for free on TV, there were fewer and fewer reasons for audiences to see them in cinemas. The ‘80s would watch grindhouse screenings of kung fu movies slowly die but, in the time they had left, Mad Monkey Kung Fu and Mystery of Chess Boxing thrived.

In 1981, the final twist in the kung fu tail entered stage left. The secret master that would kill off kung fu wouldn’t reach New York City until March of 1982, but in October 1981, between the New York premieres of Mad Monkey and Chess Boxing, Cannon Films’ Enter the Ninja premiered in Arizona and began creeping across the country. A few years later, Sho Kosugi would become the biggest Asian movie star since Bruce Lee and Chuck Norris, kung fu would be old-fashioned, and grindhouse theaters would be dominated by all of the ninjas, all of the time.

- text by Grady Hendrix

A trade ad for Enter the Ninja before star Mike Stone was replaced with Franco Nero. In fact, by the time Menahem Golan visited the set, director Boaz Davidson, listed here, had already been replaced by Emmett Alston. However, Golan was so disappointed in what he saw that he replaced Alston himself, and fired everyone in the crew except the sound man. Stone agreed to stay on as stunt choreographer.

Sources cited in this essay:

Barrbanel, Josh. “A Nether World: A Block of 42st.” New York Times, July 6, 1981.

Various. A Tribute to Action Choreographers. Hong Kong International Film Festival Publications, 2006.

Various. A Study of Hong Kong Cinema in the Seventies. Hong Kong International Film Festival Publications, 1984.

Chang Cheh. Chang Cheh: A Memoir. Hong Kong Leisure and Cultural Services Department 2002

Robertson, Tim. “The Martial Arts Resurgence of 1979.” Fighting Stars, February, 1980.

Duddy, James and Flynn, Donald. “Chinatown Gang Leader Slain in Theater.” Daily News, February 16, 1981.

Hudgins, Christine. “Bombing: Under Investigation.” Minneapolis Star Tribune, August 19, 1981.

The Deuce Film Series is a monthly, 35mm presentation created by "Joe Zieg" Berger and co-hosted with "Tour Guide Andy" McCarthy and 'Maestro Jeff’ Cashvan. Produced by Max Cavanaugh for Nitehawk Cinema Williamsburg, The Deuce was founded in November 2012.