The Taming of the Shrew (1929) has a pretty poor reputation, being a late gasp of two silent mega-stars, Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks, in the early talkie era. If it's celebrated for anything, it's for the credit "Based on the play by William Shakespeare, Additional Dialogue by Sam Taylor," which does not actually appear on the film. But the credit "Adaptation and direction" does amount to the same thing.

Like Zefferelli's discretely bawdy sixties version, Sam Taylor's movie casts a real-life celebrity couple, so instead of Burton and Taylor (no relation to Sam) we get Fairbanks and Pickford (can the Brangelina version be far behind?) and this works surprisingly well. I should qualify that by saying I find the play hard to stomach: after the amusing first act, where Kate the shrew comes on like a kind of Tasmanian Devil, destroying all in her path, it degenerates into a politically intolerable tale of spousal abuse and forced brainwashing, in which a woman's spirit is systematically broken, resulting in happiness all round. I've seen versions of The Merchant of Venice which used the anti-semitism to create an interesting sense of disquiet, which I think is genuinely there in the play (best explanation I heard is that Shakespeare set out to write Shylock as a melodramatic villain, but was too good a writer, and his creation assumed a command of our sympathies at odds with the shape of the plot), but I've never seen a version of Shrew that managed to accommodate our modern sensibilities into a play which seems to wholeheartedly endorse the view of the male characters, and eventually of Kate, that women should be mindless drones in service of their hard working hubbies.

Well, this version gets around that by throwing out the play—most of the text goes right away, so that early scenes mainly seem to consist of bracing slapstick action and characters declaiming each others' names in surprise. What's left follows the vague shape of the story up until Petrucchio and Katherine's first night of wedded warfare, at which point the play is entirely re-written: Kate overhears her other half's plan to "kill her with kindness" and subverts it, going along with his mad insistence that the moon is really the sun, thus confusing him. When he opens a window to enjoy the blasting storm, she opens the other window, even though she can barely stand in the resulting gale, and more or less literally steals his thunder. She follows his lead in rejecting the bedclothes: when he throws aside the bed-covers because of an imaginary stain, she throws aside the entire mattress, then makes her bed on the floor, quite comfortably. When all else fails, she brains him with a footstool and then nurses him back to health.

By the end of the film, Doug is convinced he's won the battle of nerves, but Mary knows she has, and her speech about a woman's place is delivered with the broadest of irony, including a wink to her sister (and us). Result: a movie that's more progressive, funnier, and easier to accept that the version made thirty-odd years later.

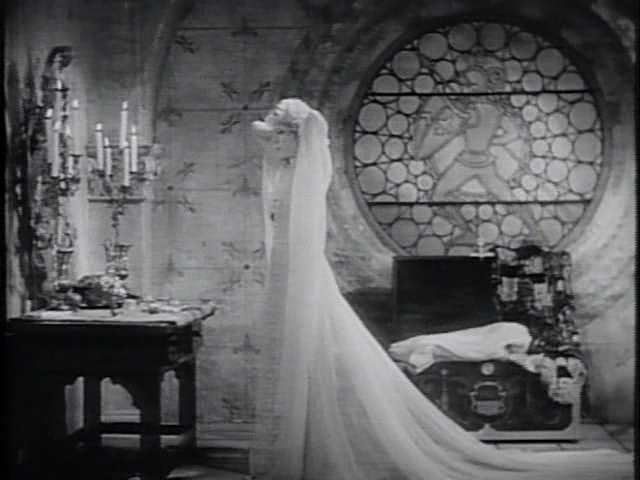

Co-designed by William Cameron Menzies, the picture is never less than handsome, combining Elizabethan fine detail (although the pack of cards used is a Ruder-Waite tarot deck, dating from the 1920s) with typical Menzies gargantuanism. Taylor moves the camera deftly, with several bravura swoops and thrusts: the crane shot that arcs up a flight of stairs to greet Pickford on her entrance is identical to a more celebrated one in the Spanish-language Dracula (1931). Music is used with surprising dexterity, anticipating much later developments in film scoring, the pace is taut and the necessity of recording a clean soundtrack with primitive equipment doesn't seem to have stopped Taylor from sound camera placement.

None of this would be worthwhile if the film weren't funny, but fortunately it is—both stars have fine voices, and we're surely past the stage where their American accents need bother us. Their comedy schtick is rather exquisite, if schtick can be called exquisite: we're talking double-takes, narrow-eyed scowls, huge grins, and textbook faffing with props. When in doubt, Doug throws a servant across the room or vaults backwards off a horse. When apparently stood up at the wedding altar, Mary performs a satiric impersonation of Doug's dynamic, stomping, pose-striking approach to dramaturgy that's wickedly accurate. Doug seems very able to laugh at himself, embracing the slightly fatuous nature of his traditional heroic stances. By the end, it's impossible to imagine any pair of actors doing it better, and if there were another Fairbanks-Pickford comedy in existence, I'd be watching it right now.

***

The Forgotten is a regular Thursday column by David Cairns, author of Shadowplay.