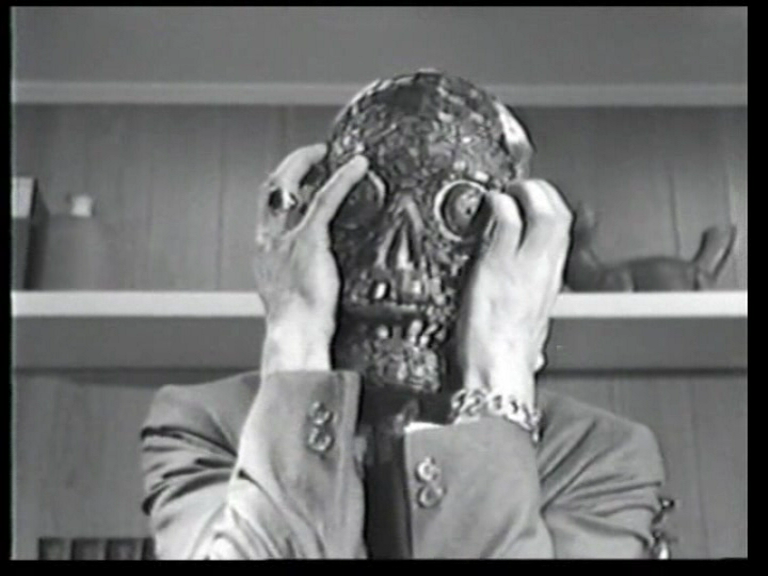

It's no surprise that the ReSearch Guide to Incredibly Strange Films used an image from Julian Ruffman's 1961 horror flick The Mask on its cover. The low-budget Canadian psycho-thriller embodies all the hallucinatory virtues of the psychotronic movie. Eschewing the conventional pleasures of a complex narrative with compelling characterisations, The Mask alternates endearingly amateurish scenes of stodgily conventional dramaturgy, with psychedelic freak-outs which don't advance the plot, but serve instead as a far more appealing alternative to it, a nightmarish abstract movie that periodically crashes into the narrative, distorting it into surreal rituals, shot in 3D and designed by Hollywood's ancient montage king, Slavko Vorkapich. Each of these scenes is preceded by a booming voice-over instructing us to --

"Put on The Mask!"

"Put on The Mask!"

"Put on the Mask!"

So our archeologist hero dons the titular skull-face and is treated to bizarre visions...

While the audience dons its tinted spectacles and does the same. If you have a pair to hand, I highly recommend it.

While the rest of the film trundles along in predictable fashion -- our hero's spells wearing the mask mess up his mind until he's committing random murders, and the mask is not only as powerful a hallucinogen as LSD, it's as addictive as crack -- the dream sequences loom out at the audience with fever-dream intensity. Ruffman and Vorkapich thrust stuff out the screen at us, to be sure, but the real merit of the 3D is the way it makes utterly alien and peculiar imagery feel present and inescapable.

Slavko Vorkapich had been MGM's top montage director in the '30s, crafting weird sequences intended to compress time and conflate events in order to move the story forward at speed where necessary, but his wild and woolly fantasy sequences -- screaming naked harpies flying over the city in Crime Without Passion (1934), cannonballs melting into skulls with Napoleon hats on in The Firefly (1937) -- were regularly slashed down to scale by the studio apparatchiks, their wildest flights of insanity quietly confined in the refrigerated asylum of the studio vaults.

The Serbian artist had made his breakthrough in 1928, co-directing with Frenchman Robert Florey the experimental short The Life and Death of 9413: A Hollywood Extra, an expressionistic satire of the studio machine that was about to consume both men. Florey became an accomplished director of genre product, some of which he imbued with a quirky flair, while Vorkapich's success as montage designer saw his name briefly become a recognized industry term for a stylized montage sequence.

So if Ruffman was no genius as director -- although his film boasts some impressive throbbing sound design -- he can be credited with at least one genuine inspiration: bringing Slavko Vorkapich out of retirement and turning him loose on a project that had no MGM supervision, no limits beyond its modest budget, and no grounding in logic or narrative sense.

***

The Forgotten is a regular Thursday column by David Cairns, author of Shadowplay.