UP, UP AND AWAY

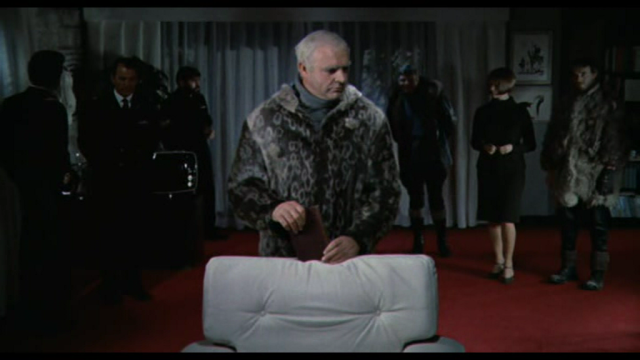

At the beginning of 1969's The Red Tent, a Soviet-Italian co-production (perhaps the Soviet-Italian co-production?), a film without a reputation, a group of ghosts gather for a mock-trial. General Umberto Nobile (Peter Finch, an unlikely Italian) has summoned them, as he does every night. He is the man on trial.

It's an intriguing start, but it soon becomes clear that this mystic-psychological framing story is essentially a ham-fisted expository device, and the movie's lack of reputation makes a little more sense. But all is not lost.

In 1928, we soon learn, Nobile captained a mission to the North Pole by airship (the film is based on a true story). This madness ended badly, as one might expect it to if one gave the matter a few seconds thought. A hair-raising sequence follows, as ice builds up on the craft's exterior, and a storm hurls the fragile balloon earthwards.

Crunch. And bounce. The cabin breaks apart, leaving several crewmembers stranded on the ice amid the debris. Terrifyingly, the airship then bounces back into the sky, carrying the others with it. Not flying. Falling upwards. Astonishing shots.

Q: Are they going to be OK?

A: Probably not. The bit left behind on the ice floe had the steering wheel in it.

The movie then swerves sharply out of disaster movie territory, shrugs off the possibility of becoming a survival-in-the-wilderness epic (although snow-blindness, frostbite and polar bear for dinner are all explored) and deals more with the bureaucracy, incompetence, and sheer bad luck that stymie rescue attempts for weeks. It doesn't seem like the most cinematically exciting approach to the story, stressing stasis and hand-wringing over determined forward movement. But it's perversely compelling.

DOWN, DOWN, DOWN

It might finally be time to explain that the director is Mikhail Kalatozov, the auteur responsible for the truly eye-popping I Am Cuba (1964), whose sinuous camera moves never seem to end, seem to work their way out of the movie and into the viewer's subconscious. His involvement promises much, but in the intervening five years, during which he had apparently not worked, something bad must have happened. The wide-angle, swaying handheld camera movements are still present in The Red Tent, but the long-take approach has been abandoned entirely, diluting one of the great visual styles of all time to the point where it barely registers at all. Possibly it's age taking its toll, along with the undoubted difficulties of filming in Arctic conditions. Only a shot where Claudia Cardinale and Eduard Martsevich roll over in the snow and the camera rolls with them has a touch of the insistent follow-at-all-costs aesthetic that has wowed cineastes from Scorsese to Paul Anderson.

As for the performances, one might remember those "American tourists" in I Am Cuba and shudder, but here the problem is different. The Red Tent is one of those Euro-puddings (no doubt an Arctic Roll) where a multi-national cast all play characters of the wrong nationality—besides Finch as Nobile, Sean Connery, reliably Scottish as Roald Amunsen, is probably the unlikeliest—and each of them simply does what they do. Claudia Cardinale is husky-voiced in a fetching bob. Hardy Kruger is hearty (cf The Flight of the Phoenix, a good man to have onside if your aircraft is stranded). Mario Adorf is Mario Adorf.

The shortcomings are shored up by some impressive spectacle and some lovely photography, the charisma of the uncontrolled cast, Ennio Morricone's music, and mostly by the very compelling true story at its heart. And the writing seems to improve in the last stages, evidently the sequences where an uncredited Robert Bolt contributed dialogue. The film suddenly becomes pithy and epigrammatic. The framing structure is still stagey at heart, but all at once it's brilliantly stagey.

A strange experience, this. From a cinephile perspective, Kalatozov's involvement causes mainly frustration, since we don't get his compelling visual approach (nor yet the contrasting, but equally strong style he deployed in earlier works such as Salt for Svanetia in 1930). But the movie is still engaging, even for non-dirigiphiles, and there's a weirdness about the whole undertaking which cannot altogether be dispelled by the sometimes stolid handling.

"It seems the jury is dismissed."