"Alone in the hissing laboratory of his wishes, Mr Pugh minces among bad vats and jeroboams, tiptoes through spinneys of murdering herbs, agony dancing in his crucibles, and mixes especially for Mrs Pugh a venomous porridge unknown to toxicologists which will scald and viper through her until her ears fall off like figs, her toes grow big and black as balloons, and steam comes screaming out of her navel." —Dylan Thomas, Under Milk Wood.

Britain's film industry in the nineteen-forties, stoked to new heights of relevance and seriousness by the mission of wartime, rolled on with considerable momentum, arguably climaxing in 1948, the year that saw production of Powell & Pressburger's The Red Shoes, Thorold Dickinson's The Queen of Spades, Olivier's Hamlet and David Lean's Oliver Twist. (It couldn't last: the same year saw the Rank Organisation introduce Production Facilities Limited, quickly nicknamed Piffle, a body intended to strategize the use of Rank's roster of stars, but which in effect led to the strangulation of creativity by red tape, as the bureaucrats began telling the filmmakers who they must cast.)

One effect of this flowering of talent was to drive up the general standard: it seems that when you have three or directors producing brilliant work in a small industry like the UK's, the ordinary workhouse filmmakers get better too, and the newcomers enter a field in which excellence seems to be not only achievable, but expected. So Daniel Birt, starting his career in 1948, was stepping into an arena where great things were expected, a rarity in the history of British movie-making.

To help him on his way, Birt had the services of a rogue genius, the poet Dylan Thomas, who had been writing drama for BBC radio and was enlisted by British National Films. Of the several script authored or co-authored by Thomas at the time, only two were shot, while The Doctor and the Devils and Rebecca's Daughters were finally filmed in 1985 and 1992, by which time the local mainstream had well and truly run out of inspiration.

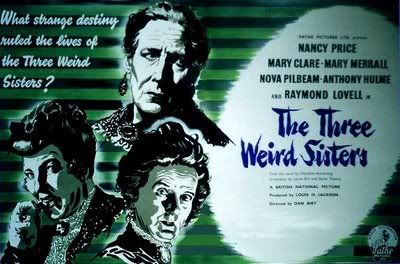

Birt and Thomas's first film, The Three Weird Sisters, deserves to be better known. If it's not perfect, it shows bursts of both verbal and cinematic energy and imagination that bely its spooky house narrative and gothic thriller origins (a novel by the oft-adapted Charlotte Armstrong). The setting is a small Welsh village, dead on its feet since the closure of the coal mine, and with a steadily aging populace. In scene one, an entire street collapses into the earth, which seems a striking way to begin a movie, even if the calamity is presented using the language of the radio play Thomas used so fluently. A loud crash is heard, and the three old ladies of the local manor scurry about with lanterns wondering what has happened. At the scene of the disaster, horrific sights are evoked solely through the reactions of onlookers: when a wardrobe is removed from on top of a crushed victim named Jack Richards, it's observed that old Jack still has his pipe in his mouth.

"We cannot understand. Only God understands. He understands everything."

"Well he didn't understand Jack Richards. Old Jack wanted to live. Why, he'd just done his pools."

The speaker is a startlingly young Hugh Griffith (although Hugh Griffith was never actually young, sporting even in infancy the giant ears and nose and the freely sprouting eyebrows of the septuagenarian), who would later win an Oscar for Ben Hur, playing an arab with a Welsh accent. Here, he's maybe British film's first respectable free thinker, part of a running vein of anti-clerical humour that enlivens the film and makes it a rather startling product of the culture at that time.

The old sisters (one blind, one deaf and one crippled with arthritis) feel responsible, since they should have ensured that their mine was filled in after it closed. They don't have the money to pay for the (pointless) reconstruction of the street, so they petition their wealthy half-brother, the offspring of their father and the cook, regarded as their inferior although he's the wellspring of their finance. Nominally hard-headed, but living in terror of his witchy older siblings, he departs London for South Wales with his secretary in order to give them a definite "no."

Wales, of course, was the setting of James Whale's The Old Dark House, a fact you're unlikely to forget as The Three Weird Sisters unfolds. The blind, yet seemingly all-seeing matriarch, played by Nancy Price, presides with queenly froideur over her sisters, the twitchy and twisted Mary Merrall, and the stone-deaf Mary Clare, who plays with a kind of imbecile malevolence reminiscent of Tubbs, the psycho shopkeeper in TV's The League of Gentlemen. The movie is unregenerate in its typing of the disabled as inherently untrustworthy and wrong. There's a slow-witted handyman too who's persuaded to help the ladies in their schemes.

These schemes—basically, a plot to murder their half-brother and get his money—make up the bulk of the story. The brother has a plucky and resourceful secretary (Nova Pilbeam, from Hitchcock's first The Man Who Knew Too Much and Young and Innocent) and she tries to protect him. The sisters try poison, gas, and a contrived road accident. The village doctor, positioned as leading man, has to be extraordinarily dense for quite a long time in order to not realize what's afoot, and once he does wise up the plot has to contrive reasons for the potential murderee not to escape right away. Plot wasn't Dylan Thomas's strong suit, one feels, nor anyone else's. But instead we have atmosphere and a real flavor of dark, rural Wales, a rarity in the London-centric British cinema.

Most of the great stuff is verbal or performance related, but Birt manages a few nice pieces of atmosphere, including one of those slow tracking shots onto a softly rotating doorknob that show a feeling for the Gothic which is honest and unashamed, and there's one extraordinary scene where the sheer sinister aspect of the sisters causes young Nova to swoon. The build-up is a Ken Russell style stroboscopic montage of giant eye closeups, quite out of character for 1948. And all followed by a gloriously sinister line reading from Mary Clare: "We were all so surprised when you fainted! I liked you when you fainted."

Apart from the creepy characters and rich, evocative dialogue, the movie also boasts a splendid climax, lifted from Poe, with the evil old house (a microcosm of Wales, perhaps, signifying Thomas's conflicted relations with his homeland) collapses into the earth. The apocalypse is followed by a homily delivered by the village priest, and a knowing look exchanged between the leads as he recites the charitable deeds and Christian nature of the three Great Ladies.

Stop Press: I get this far in the article before watching Birt and Thomas's No Room at the Inn, a drama about homeless children in wartime forced to stay in a disreputable house with another female monster, Mrs. Voray (Freda Jackson, later a regular in Hammer horrors), and I abruptly realize I may be writing about the wrong film. For while The Three Weird Sisters is a semi-successful genre piece with outstanding elements, the follow-up, while less cinematically exuberant, is an emotional powerhouse with a truly appalling and briliant characterization at its center. Mrs. Voray is a grotesque slattern and comic malaprop ("Are you incinerating I'm offensive?" and "We must have a teat-a-teat."), able to volte-face into a sanctimonious, simpering plaster saint at a moment's notice. Never mind Alec Guinness's (anti-semitic) caricature of Fagin, this was the cartoon creation of the year, terrifying and hilarious and so much fun to hate.

***

The Forgotten is a regular Thursday column by David Cairns, author of Shadowplay.